FANNIE LOU HAMER -- IS THIS AMERICA?

CLICK TO HEAR FIVE FREEDOM SONGS

INCLUDING TWO SUNG BY FANNIE LOU HAMER

RULEVILLE, MS, JUNE 1962 — Rattling through the sunburnt Mississippi Delta, civil rights workers broke into song. “Wade in the Water.” “Oh, Freedom.” “This Little Light of Mine.” Everyone on the bus knew these “Freedom Songs.” Everyone joined in. But one voice soared above the others. Deep and sorrowful, it seemed rise from the Mississippi clay. Soon all of America would hear that voice.

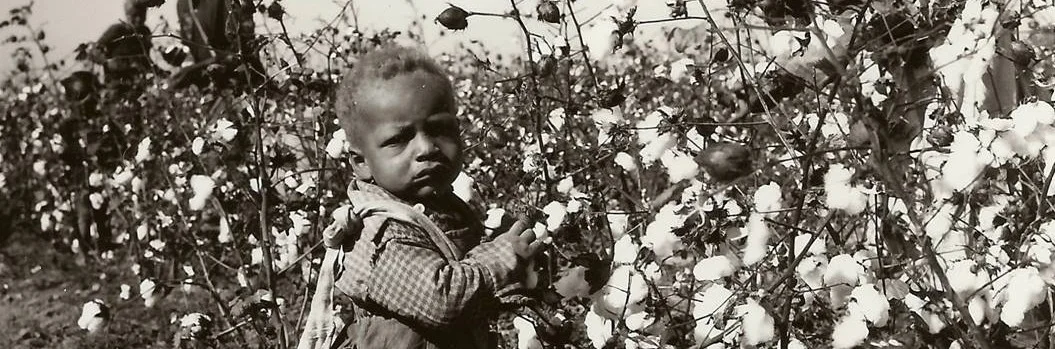

All her life, Fannie Lou Hamer bristled at how Mississippi treated her. Growing up barefoot, hungry, wishing “so bad” that she was white, she watched her father save to buy wagons only to have a white man poison his mules. Worn down by picking cotton, Hamer had two stillborn children. Then in 1961, she entered the hospital with “a knot on my stomach” and, without her consent, was sterilized. Something had to change. As she often said, “I’m sick and tired of being sick and tired.”

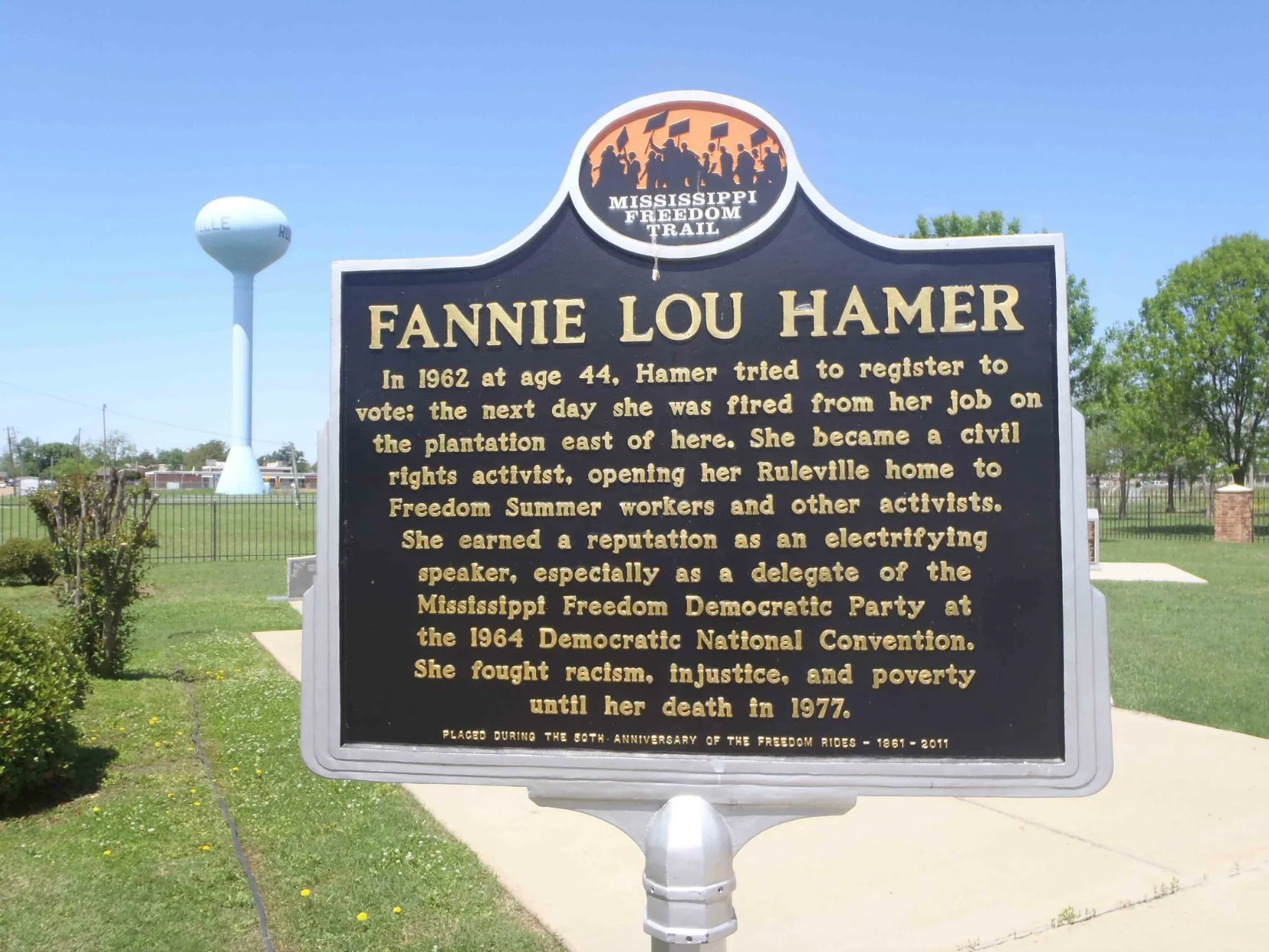

In a steamy Delta church, in the summer of 1962, Hamer heard activists explain her right to vote. If enough blacks registered, they could vote bigoted sheriffs out of office. Volunteers? Hamer’s hand shot up “as high as I could get it.” Days later she was at the Sunflower County courthouse. The registration test, crafted to keep blacks from voting, asked her to explain de facto laws. “I knowed as much about a facto law as a horse knows about Christmas Day,” she recalled. Rejected, she came home to find the “boss man raisin’ Cain.” She had damn well better withdraw her registration, she was told, because “we’re not ready for that in Mississippi.”

“I didn’t try to register for you,” Hamer told the “boss man.” “I tried to register for myself.” Thrown off the plantation, shot at, beaten, Hamer became a civil rights legend. When she moved, black Mississippi moved with her. When she threw her head back and sang, “you could hear her all over Sunflower County.” She scoffed at the risks. “The only thing they could do to me was kill me and it seemed like they’d been trying to do that just a little bit at a time since I could remember.”

Until the summer of 1964, Mississippi alone knew Fannie Lou Hamer. But at the end of Freedom Summer, after three murders and dozens of church burnings, she took the national stage.

Mississippi Freedom Democrats had bused to the Democratic National Convention. Claiming they, not an all-white delegation, should represent Mississippi, Freedom Democrats appealed to the conscience of the Democratic Party. The challenge dragged on. A rattled LBJ considered refusing the nomination. But when Fannie Lou Hamer sat before the Credentials Committee, Johnson called a hasty press conference, diverting network coverage. (See the story on the video below). Hamer spoke and TV carried her voice to the nation.

“Mister Chairman, and to the Credentials Committee, my name is Mrs. Fannie Lou Hamer. . . “ A worried look came over her, but she steeled herself. Later she said she felt as if speaking from a mountaintop. “It was the 31st of August in 1962 that eighteen of us traveled twenty-six miles to the county courthouse in Indianola to try to register to become first-class citizens. . . .“ Blow by blow, she told America about her arrest, detention, beating. . .

“And he said, ‘We're going to make you wish you was dead.’. . . And I was beat by the first Negro until he was exhausted. . . the state highway patrolman ordered the second Negro to take the blackjack. . .” Rising to righteous fury, she challenged the entire nation:

“All of this is on account of we want to register to become first-class citizens. And if the Freedom Democratic Party is not seated – NOW –- I question America. Is this America? The land of the free and the home of the brave? Where we have to sleep with our telephones off of the hooks because our lives be threatened daily. Because we want to live as decent human beings, in America?”

If not brimming with rage, she might have repeated -- “Is this America?” “Is this America where. . . .?” But with her voice wavering, she said “Thank you,” stood and walked off the mountaintop.

Despite calls from around the country, Freedom Democrats were offered two non-voting seats. They left in disgust. “We didn’t come all this way for no two seats,” Hamer said. But Democrats also promised there would be no more all-white delegations. And there weren’t.

In 1968, Hamer spoke to the entire Democratic Convention, from the podium. Four years later, she was a Mississippi delegate. When she died in 1977, her grave was chiseled with her motto: "I am sick and tired of being sick and tired.”