W.E.B. DUBOIS -- LIFTING THE VEIL OF RACE

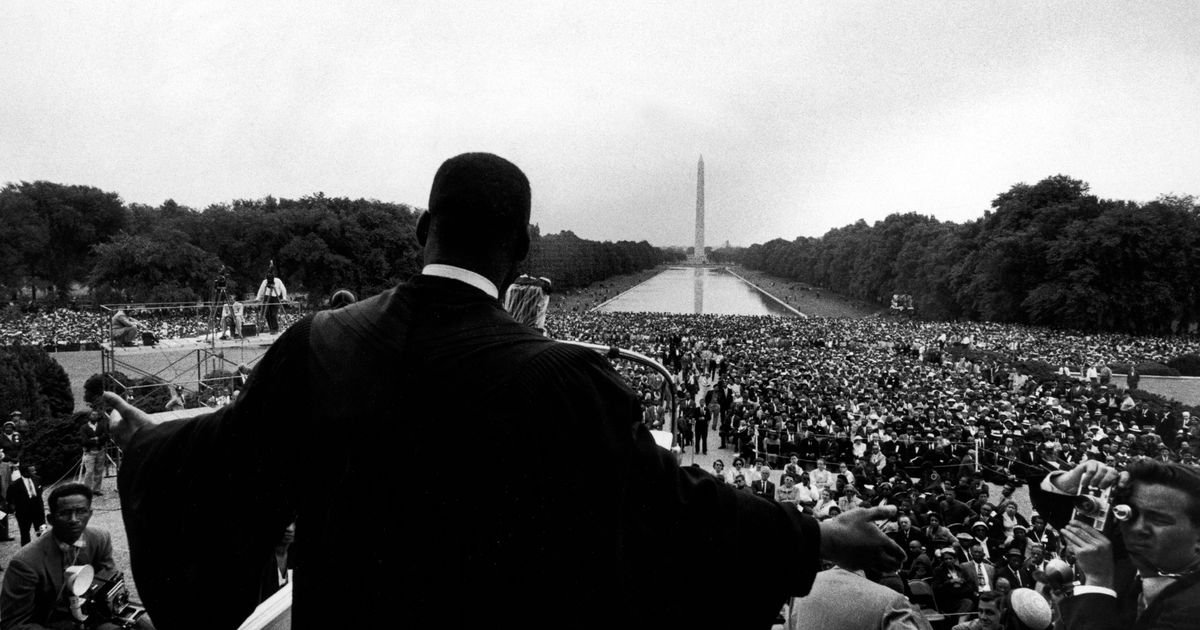

August 28, 1963 -- From across America buses converge on Washington, D.C. Fifty, perhaps 100,000 people are expected, but by mid-morning, a quarter million fill the great mall. The March on Washington has been called by Martin Luther King, but before he can describe his dream, there comes another call, long distance.

From the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, NAACP chairman Roy Wilkins shares sad news. A man most blacks know well but few whites have heard of has just died -- in Africa. An old man. A black man. A prim, goateed man far bigger than his 5'5". "At the dawn of the twentieth century," Wilkins tells the crowd, "his was the voice that was calling to you to gather here today." Then Wilkins recommends a book published in 1903.

The early 1900s, one scholar noted, marked "the nadir of the Negro in America." Hardly a week passed without a lynching. Jim Crow laws had ended black voting, cordoned the South into "Whites" and "Coloreds," and spawned such screeds as The Negro -- A Beast. Into this offal, an unknown scholar threw a single book. Its first paragraph proclaims, "The problem of the Twentieth Century is the problem of the color line."

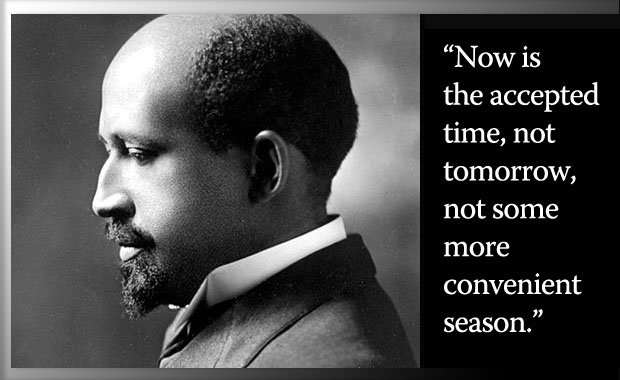

William Edward Burghardt DuBois (pronounced Du-BOYS), was not born into poverty or slavery. Growing up in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, DuBois was one of 50 blacks among 5,000 whites. Recognizing his gifts, the town took up a collection for his college tuition. DuBois studied at Fisk, then in 1895 became the first black to get a Ph.D. from Harvard. He might have settled for scholarship at some white-steeple New England college, but DuBois would never settle for anything less than justice.

DuBois faced plenty of racism at Harvard, where he was regarded as a curiosity more than as a human being. But while teaching at Atlanta University, he "saw the race-hatred of the whites as I had never dreamed of it before -- naked and unashamed!" He witnessed a lynching, then a riot as whites rampaged through black neighborhoods. Later he remembered, "with this came the strengthening of and hardening of my own character." And in Atlanta, he published The Souls of Black Folk. Many whites doubted that blacks had souls, but DuBois saw sorrowful spirits torn in two by their treatment.

"It is a peculiar sensation, this double consciousness, this sense of always looking at one's self through the eyes of others. . . One ever feels his two-ness -- an American, a Negro, two souls, two thoughts, two unconcealed strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body, whose dogged strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder."

READ A SAMPLER FROM THE SOULS OF BLACK FOLK IN THE DUSTY BOOKSHELF

Souls enraged some, brought others to tears. The book, now a classic, is a blend of genres. Chapters include a history of Reconstruction, a visit to a black church, a short story, a call to education, and a loving tribute to Negro spirituals. But what stood out in 1903 was DuBois' battle with Booker T. Washington.

Washington had risen from slavery to become America's most celebrated black man. As founder of Tuskegee University, Washington preached hard work and modest ambition. Slavery had helped blacks, he said, and segregation should be accepted. "In all things that are purely social we can be as separate as the fingers, yet one as the hand in all things essential to mutual progress."

DuBois respectfully disagreed, then let Washington have it. "The way for a people to gain their reasonable rights is not by voluntarily throwing them away. . . Negroes must insist continually, in season and out of season, that voting is necessary to modern manhood, that color discrimination is barbarism, and that black boys need education as well as white boys."

In the wake of Souls, DuBois spent sixty years that can scarcely be summed up here. Co-founder of the NAACP. Fiery editor of its newsletter, The Crisis. Present at the creation of the United Nations. Persecuted, in his eighties, by McCarthyism. Invited, at 91, to Ghana where he died on the eve of the March on Washington. DuBois, said one NAACP founder, had been "battering his life out against ignorance, bigotry, intolerance and slothfulness. . . and raising hopes for change which may be comprehended in a hundred years.

The final words should be his. The Souls of Black Folks barely mentions racism, instead describing a "veil" between whites and blacks. In 1897, long before Dr. King, W.E.B. DuBois had a dream -- of lifting this veil. "Beyond the Veil lies an undiscovered country, a land of new things, of change, of experiment, of wild hope and somber realization, of superlatives and italics -- of wonderfully blended poetry and prose."