THIS IS LONDON!

AMERICA AUGUST 25, 1940 — Mired in the Depression, Americans scof at radio news. History’s wildest “fake news” — Martians invading New Jersey! — just caused a minor panic. Nightly news runs just 15 minutes, some guy in a studio droning newspaper headlines into a mic. So how can radio, the medium of soap operas and sermons, be trusted with news? Then a tough, chain smoking reporter goes live from London.

Radio’s Saturday night lineup includes a dance orchestra and a hit parade. But at 6:30 p.m., on big, boxy radios in living rooms across America, broadcast news came of age. Don’t take my word. Click to Hear it Now.

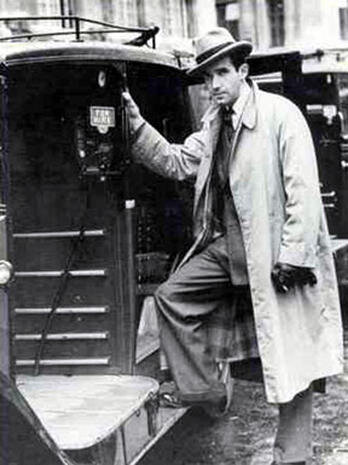

Edward R. Murrow had no training in journalism. Raised near Seattle, he majored in speech at a state college. He started out directing student foreign exchanges but was bored and eager to prove himself. So in 1935, he joined CBS in New York. The network had one news reporter. Murrow’s job was to find newsmakers to speak on the air.

In 1937, CBS sent Murrow to London to woo European newsmakers. He was in Vienna one night when the CBS’ correspondent was out of town. And Hitler had just annexed Austria. Murrow took microphone in hand. “This is Edward Murrow speaking from Vienna. It's now nearly 2:30 in the morning, and Herr Hitler has not yet arrived."

As war loomed, Americans began tuning in his nightly reports. Other broadcasters signed on, “Hello, America — this is London speaking!” But Murrow began: “This — is London!” Soon CBS news in New York was “calling Ed Murrow. . . come in, Ed Murrow!”

Of Murrow’s many gifts, the first was courage. As Nazi bombers blitzed London, other correspondents ducked. But Murrow was on the street, even on rooftops. Stories spread. How Murrow had been dining out when a bomb hit. Murrow just looked under the table, said “I dropped my watch,” then went back to his dinner.

A greater gift was eloquence. Radio had no pictures, so Murrow put them in listener’s heads. Click to hear more.

Live at the scene, Murrow spun images a novelist could envy.

— “The searchlights bored into that black roof but couldn’t penetrate it. They looked like long pillars supporting a black canopy.“

— “The first two [bombs] looked like some giant had thrown a huge basket of flaming golden oranges high in the air. The third was just a balloon of fire.”

But Murrow’s greatest gift was faith in people. Hitler thought nightly bombing would crack the British, but each morning Murrow saw bodies removed, bodies “like broken, castaway, dust-covered dolls.” “I’ve seen some horrible sights in this city,” he reported, “but not once have I heard man, woman, or child suggest that Britain should throw in her hand.”

Murrow also believed in the American people. He professed “an old-fashioned belief that Americans like to make up their own minds on the basis of all available information. The conclusions you draw are your own affair.”

With Murrow reporting, Americans concluded that the war was worth the struggle. And in early December 1941, when Murrow came home to a banquet at the Waldorf-Astoria, poet Archibald MacLeish summed up a nation’s gratitude.

“You burned the city of London in our houses and we felt the flames that burned it. You laid the dead of London at our doors and we knew that the dead were our dead, were mankind’s dead. You have destroyed the superstition that what is done beyond 3,000 miles of water is not really done at all.” When Murrow stood, a thousand people rose to applaud. A few days later came Pearl Harbor. On December 7, Murrow dined at the White House, then went back to London.

Embedded long before that term became cliché, Murrow went on 25 bombing missions, taking listeners along. Paratroopers looked “like khaki dolls hanging beneath a green lampshade.” Berlin under bombing became “a kind of orchestrated hell, a terrible symphony of light and flame.” Murrow was with troops liberating the concentration camp at Buchenwald. Scarcely comprehending its horror, he concluded, “I pray you to believe what I have said about Buchenwald. I have reported what I saw and heard, but only part of it. For most of it I have no words. . . If I've offended you by this rather mild account of Buchenwald, I'm not in the least sorry.”

You hear a lot these days about how journalists are “the enemy of the people.” Don’t believe everything you hear. Commentators spew opinions. Politics plays left, plays right. But for those in the field, the standards were set 80-some years ago and there isn’t one reporter, about to go live from a war zone or disaster site, who doesn’t summon the spirit — and the courage — of Edward R. Murrow.