FREDERICK DOUGLASS' FOURTH

ROCHESTER, NY, JULY 4, 1852 — Another Fourth of July passed quietly. Then on the Fifth, thunder struck.

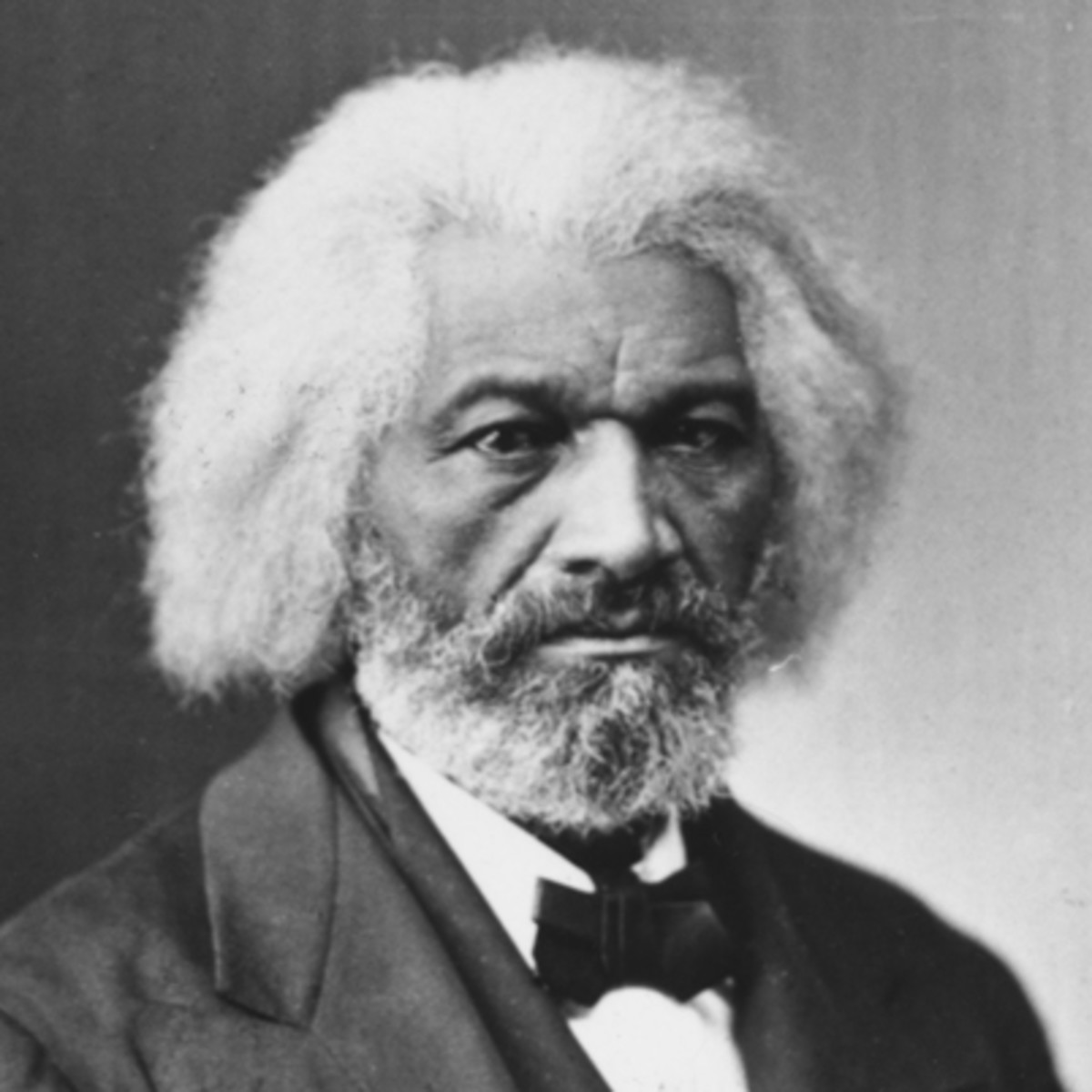

That afternoon, the Anti-slavery Society gathered in Corinthian Hall. The speaker called his talk “Oration.” He began with praise for the city, the nation, the holiday. Then Frederick Douglass spoke truth to Independence Day.

Standing like a pillar between columns backing the stage, Douglass paused. “Fellow citizens, pardon me. Allow me to ask. Why am I called upon to speak here today? What have I, or those I represent, to do with your national independence?"

Many in the audience winced, because all knew Frederick Douglass’ story. Born into slavery. Never knew his father other than that he was white, which made Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey the child of rape. Lost his mother at age eight. Lived as a “house Negro.” Was taught to read and write — a crime in those days.

And all in the audience knew how, at age 18, he plotted his escape, was caught and flogged. All knew how, two years later, disguised as a sailor, he walked out of a Baltimore shipyard, boarded a train, a ship, another train, and never looked back. Yet always looked back. America knew Frederick Douglass, yet few had felt the sting of hypocrisy he now summoned.

“I do not hesitate to declare with all my soul that the character and conduct of this nation never looked blacker to me than on this Fourth of July!”

By 1852, four million American slaves lived as far from independence as any human could. Douglass had spoken, written, lobbied, debated. But he also lived his values.

A century before Rosa Parks, Douglass refused to give up his seat in all-white train car. He was dragged out. A century before Brown v. Board of Education, he insisted his daughter go to public school. One principal agreed, but then Douglass learned his daughter was being tutored in secret. So he had the principal poll students. All wanted Rosetta Douglass in their class. One parent objected and the girl was turned away. Douglass put his daughter in a private academy, but his fight continued.

At the podium, Douglass now rose in fury. He quoted scripture. By the rivers of Babylon “they that carried us away captive, required from us a song.” But his song was a dirge, haunted by the Fourth.

Other abolitionists called the Constitution “a slave document.” Douglass would have none of that. “There is consolation in the thought that America is young. Great streams are not easily turned from channels, worn deep in the course of ages. They may sometimes rise in quiet and stately majesty and inundate the land, refreshing and fertilizing the earth with their mysterious properties.” Yet, he warned, “they may also rise in wrath and fury. . .”

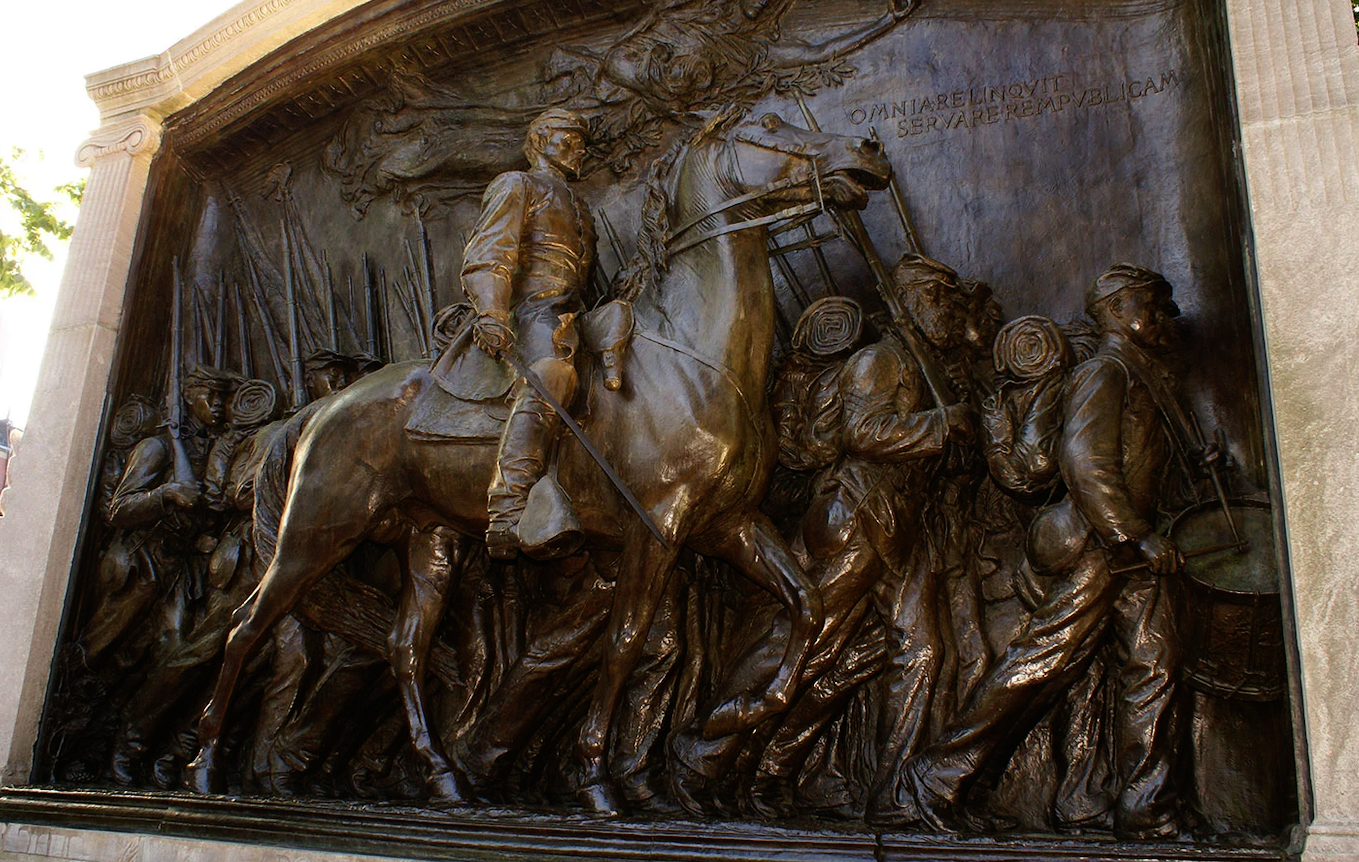

His prophecy would soon come true. When the Civil War broke out, Douglass lobbied President Lincoln to enlist black troops, then sent his own sons to fight. After the war, he served as an American diplomat and eminence grise — the most photographed American of the century. But on this day in Rochester, he trained all his energy on the Fourth, the Fourth.

“What, to the American slave, is your Fourth of July? I answer: a day that reveals to him, more than all the other days in the year, the gross injustice and cruelty to which he is the constant victim.” Yet the Fourth of July was not just a holiday but a promise.

“Cling to this day,” Douglass told the audience. “Cling to it, and to its principles, with the grasp of a storm-tossed mariner to a spar at midnight.” For “at a time like this, scorching iron, not convincing argument, is needed. . . It is not light that is needed, but fire. It is not the gentle shower, but thunder. We need the storm, the whirlwind, and the earthquake.“

Douglass’ “Oration” lasted an hour. When he finished, the audience rose to its feet. It had been, historians agree, “the greatest anti-slavery oration ever given.”

Frederick Douglass stepped from the podium, then walked into the summer heat. There was another issue of his abolitionist newspaper to print. And more fugitive slaves waiting outside its office, waiting for safe transport to Canada. On the Underground Railroad, Rochester was often the final stop.