RIDING THE MIRACLE RAILS -- "NOTHING LIKE IT IN THE WORLD"

SIERRA NEVADAS, CALIFORNIA — We are 21st century Americans riding a train through history.

Here on the upper deck of this observation car, there are Californians on vacation, Midwesterners heading home, seniors enjoying the scenery. There are Mennonite families, men with moon cheeks and bushy beards, women in long dresses and cupcake caps. A young girl taps her phone the entire trip. And then there’s me, eager to take any train, anytime, to wherever. The train tumbles on, following the route laid in the 1860s when there was “nothing like it in the world.” There still isn’t much to rival it. Come along.

Climbing out of Sacramento, this was the Western leg of the Transcontinental Railroad. Opened to worldwide amazement in 1869, the 2,000 miles of track bridged a continent and gave a once-in-a-lifetime journey to pioneers weary of wagons and "Westward Ho!" Braving spring landslides and winter snow drifts, this Sierra route also defied death by crossing the pass whose name — Donner — still haunts these mountains.

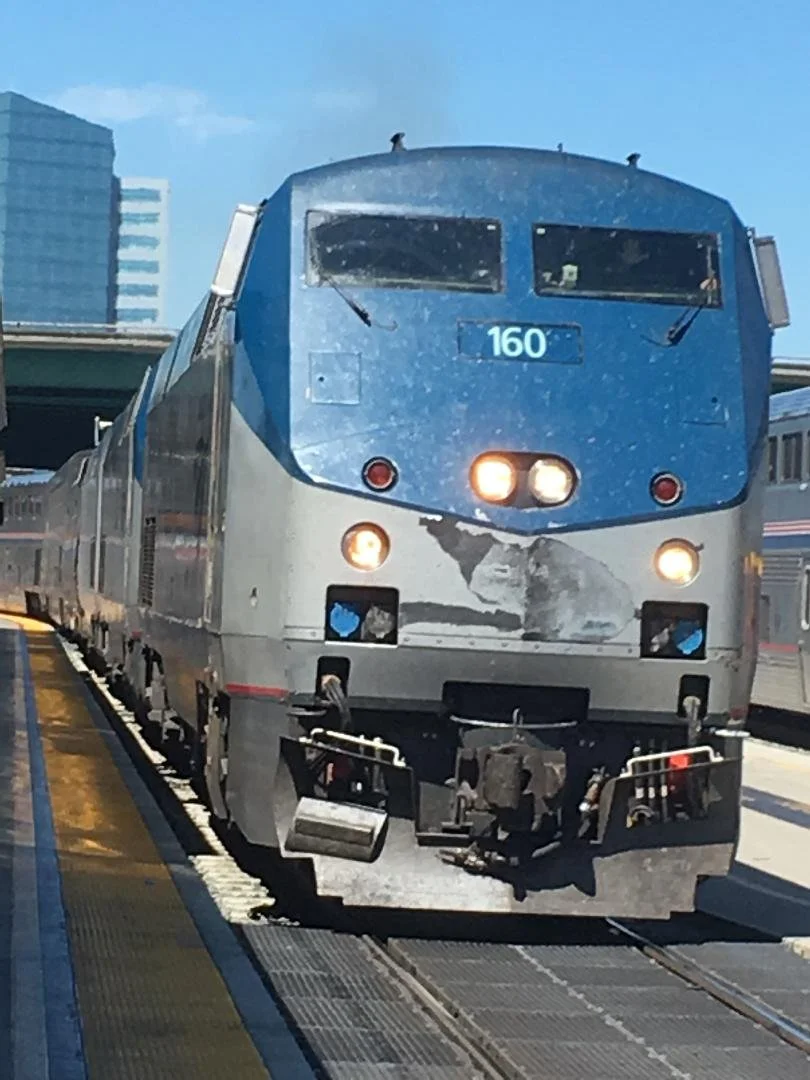

Today we ride Amtrak’s California Zephyr, making the journey daily, making it seem easy. On other trains, you dig up your own history, but as if our fare were a Disneyland E ticket, our observation car has a narrator.

On your left is the canyon. . . On your right, this pass. . . The first settlers who came through here. . . We have 82 miles and 6,622 feet to the Sierra summit.”

When this miracle broke ground, the U.S. was embroiled in Civil War. But great things can come from divided nations when they see beyond the divide. And so, money and land were allotted, railroad companies hired. The Central Pacific in California. The Union Pacific in Nebraska. In 1863 one started east from Sacramento. Months later, the other headed west from Omaha. We are riding on their hard labor.

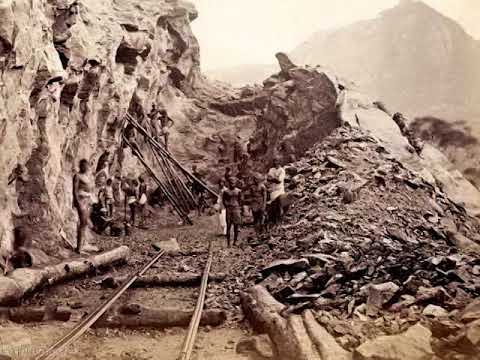

Now we are at 2,000 feet, sliding along trackbeds blasted by immigrants — Chinese and Irish. The Chinese proved to be the heartiest workers. “Without them,” Central Pacific president Leland Stanford told Congress, “it would be impossible to complete the western portion of this great national enterprise.”

Some 150 “Celestials,” buried by rubble, tumbling from baskets dangled over cliffs, died on this route. Their bodies were recovered, then laid in shallow graves to be dug up later and shipped home to China. But before we can consider their sacrifice, the tunnel opens to reveal a canyon of pine and spruce carved by the American River. That’s the river shimmering a thousand feet below. Thunderheads billow ahead, but they won't concern us until afternoon when we’ll be in Truckee or Reno or beyond. . .

At 4,700 feet we traverse more tunnels, blasted by dynamite, five tons per day. Soon we tunnel through trees, pines towering above the high windows of the observation car. In the car, the people come and go and talk of. . . America.

“Memphis is a nice town. I was just there last month.”

“Well, all I remember is being a kid and hearing about the Donner Party and how they were eatin’ each other. . .”

“Ever read Larry McMurtry?”

“Are you kidding? Lonesome Dove is my bible. . .”

And now come the snow sheds the workers called “the longest barn in the world.” Thirty-seven miles of wooden sheds protected the railroad from avalanches. Cement sheds later replaced them. Even so, in 1952, 226 passengers and crew were stranded here at Yuma Pass, their train entombed under 16 feet of snow. After four days, all were dug out, then driven out by car.

We pass ski resorts, the shaved slopes of Sugarbowl and Soda Springs. Finally we come to The Big Hole, a two-mile tunnel topping Donner Pass. Even using dynamite’s upgrade — nitroglycerin — it took two years to finish the tunnel. Rocking and rolling, we cruise through in six minutes. And then, an hour after we started our climb, we head down the back side.

To finish this great national enterprise, all they had to do was lay track DOWN the mountain, then head out across the Nevada desert. Gaining momentum, Central Pacific crews laid ten miles of track in a single day — still a record. Ahead, somewhere in Utah, there was a gold spike waiting. And on May 10, 1869, when Leland Stanford raised his hammer and brought it down, a telegraph wired to the spike flashed the message from coast to coast. “DONE!”