THE WOMAN WHO SAID 'NO' TO MCCARTHY

WASHINGTON, DC — 1950 — A bully was stalking the nation’s capital. Insulting people, ruining reputations, using fear to bend Congress to his will. Behind the scenes, many said someone should stand up for American values. Someone from the bully’s own party.

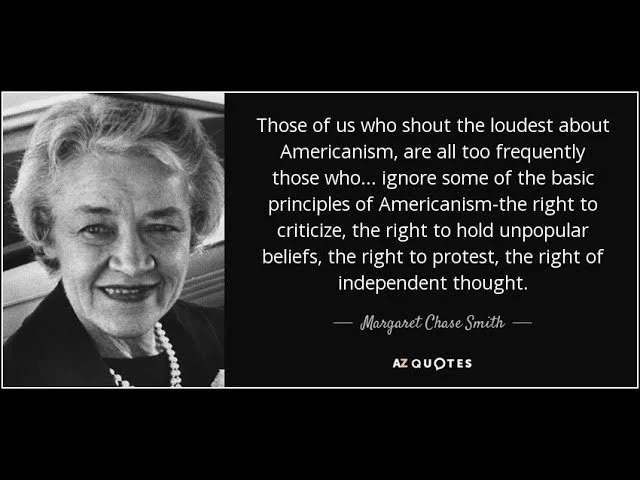

Margaret Chase Smith had served just a year in the Senate, yet “in those days,” she recalled, “freshmen senators were to be seen and not heard, like good children.”

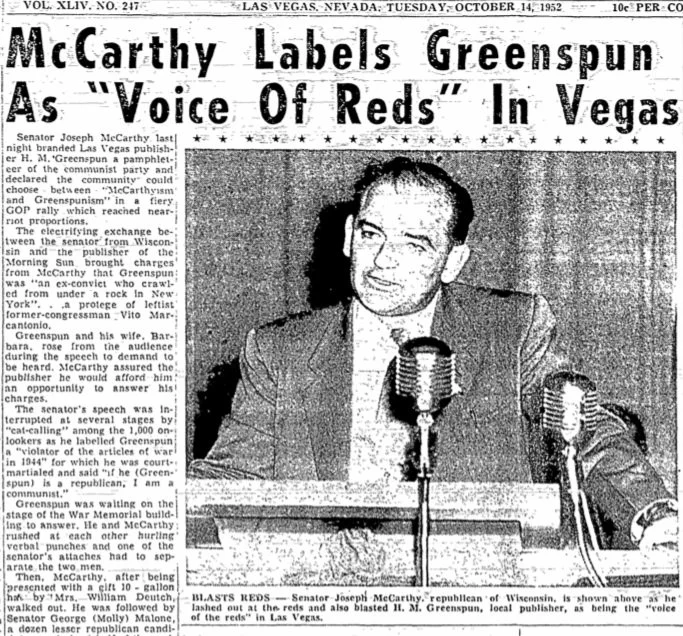

When Joseph McCarthy produced a list of 205 Communists in government, Smith trusted him. “It looked as though Joe was onto something disturbing and frightening,” she said. But then she studied the documents McCarthy offered as evidence. She saw no evidence.

At first, she wavered. “I am not a lawyer,” she thought. “After all, Joe was a lawyer and any lawyer Senator will tell you that lawyer Senators are superior to non-lawyer Senators.” Surely “one of the Democrats would take the Senate floor.” But when no challenge came, “it became evident that Joe had the Senate paralyzed with fear.”

Back in Skowhegan, Maine, folks knew Maggie Chase. Her father was a barber; her mother worked in shoe factories. Maggie went straight from high school into teaching, then journalism. Only when she married her publisher, Clyde Smith, did she enter politics, accompanying Mr. Smith to Washington when he was elected to Congress during the New Deal. When he died four years later, she won a special election, then won four elections on her own, racking up 60-70 percent of the vote.

Though beloved in Maine, D.C. knew Smith for her attire, not her expertise. Nattily dressed, she always wore a red rose in her lapel. And that was all Congress expected from the junior senator from Maine. But then she gave Congress a lesson in integrity.

As McCarthy grilled one accused communist after another, Smith began to speak out. The American people, she wrote in her nationally syndicated column, need “written evidence in black and white instead of conflicting oral outbursts in nebulous hues of red and pink.” The inquisition continued.

On June 1, 1950, as Smith boarded the Senate tram, McCarthy approached. “Margaret,” he said, “you look very serious. Are you going to make a speech?”

Smith remained as unfluttered as the rose in her lapel. “Yes,” she said, “and you will not like it.” When McCarthy asked if the speech was about him, she replied, “Yes, but I’m not going to mention your name.”

“Remember, Margaret,” he said. “I control Wisconsin’s twenty-seven convention votes.” Wasn’t she rumored to be in the running for vice-president?

Ten minutes later, Senator Smith sat on the Senate floor, three rows in front of McCarthy. “This is awful,” she said to her aide. “I’m new here, not only a new member of the Senate but a woman. And I’m getting up and telling that Republican crowd —”

Her aide stopped her: “Remember,” he said, “you came in with a whale of a vote from Maine. They have great confidence in you.” And she rose to deliver her Declaration of Conscience.

“Mr. President, I would like to speak briefly and simply about a serious national condition.” She spoke for fifteen minutes. She spoke “as a Republican, as a woman, as a United States senator,” but also “as an American.” Her words echoed through the chamber. “. . . selfish political opportunism. . . A forum of hate and character assassination. . .”

“The American people,” she said, “are sick and tired of being afraid to speak their minds. . . The American people are sick and tired of seeing innocent people smeared. . . I do not want to see the Republican Party ride to political victory on the Four Horsemen of Calumny — fear, ignorance, bigotry, and smear.”

Smith expected McCarthy to rise in defense. But he sat, the New York Times noted, “white and silent, hardly three feet behind her.” Then, without a word, he walked out. Smith accepted congratulations from a few senators, then business as usual resumed.

The press was divided. Praise came from the Times and Washington Post, attacks from the right. Yet mail from Maine backed her by 8-1. And financier Bernard Baruch said, “If a man had made the Declaration of Conscience, he would be the next president of the United States.”

Three weeks after Smith’s speech, when the Korean War broke out, Smith’s “political nightmare” shifted into high gear. McCarthy booted Smith off his committee and there was no more talk of the vice-presidency.

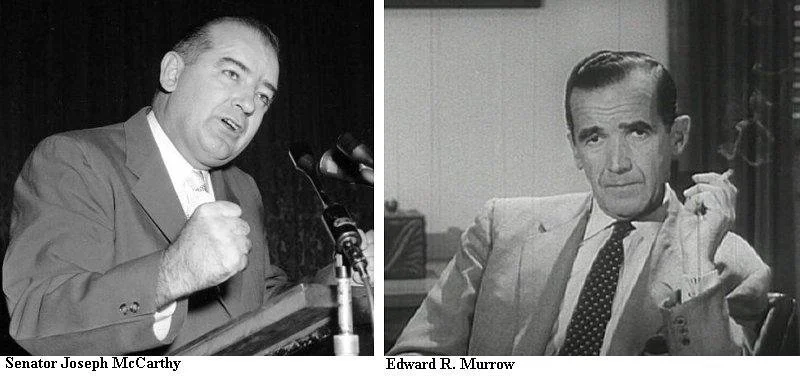

Finally in 1954, broadcaster Edward R. Murrow picked up the gauntlet thrown down by Margaret Chase Smith. Murrow’s “See It Now” program showed McCarthy bullying, snickering, making utterly false charges. Murrow concluded with a promise. “We will not be driven by fear into an age of unreason, if we dig deep in our history and our doctrine, and remember that we are not descended from fearful men...”

Nor from fearful women. Draw your own conclusions.