CAMPING WITH JOHN AND TEDDY

THE WEST — 1903 — Of the sprawling herds that once roamed the Plains, just 1,000 buffalo remained. Half of America’s old growth forests had been clearcut. “The American had but one thought about a tree,” the president said, “and that was to cut it down.” And then in the spring of 1903, Theodore Roosevelt wrote to John Muir.

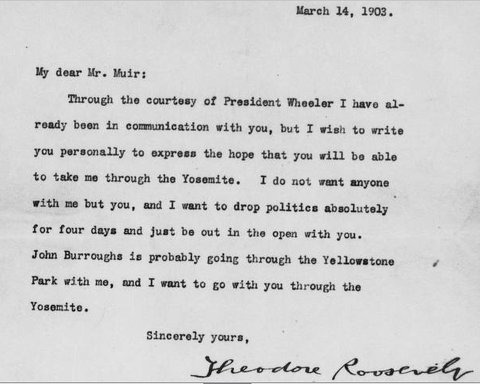

“I wish to write to you personally to express the hope that you will be able to take me through the Yosemite. I do not want anyone with me but you, and I want to drop politics absolutely for four days and just be out in the open with you.”

As a young man, John Muir had walked from Wisconsin to the Gulf of Mexico. Moving on to California, he hiked into the Yosemite Valley. “The mountains are calling,” he wrote to his sister, “and I must go.”

But by 1903, Muir was 65. Craggy with a bushy-beard, he was reluctant to go camping with America’s youngest president, that boyish champion of “the strenuous life.” Muir had planned a trip to Europe, but friends at the Sierra Club, which Muir co-founded, thought otherwise. Finally Muir agreed. “An influential man from Washington wants to make a trip into the Sierras with me,” he wrote, “and I might be able to do some forest good in freely talking around the campfire.”

Yosemite was already a national park, yet much of it remained in state hands, still endangered. “Just now while protective measures are being deliberated languidly,” Muir wrote, “destruction and use are speeding on faster and farther every day. The axe and saw are insanely busy.” Perhaps this president could change that.

Before becoming president, Roosevelt had climbed the Matterhorn and ranched in the Dakotas. He hiked the Adirondacks, the Rockies, the mountains of Maine. But could he stand up to the timber industry? To Congress? What would the president and the naturalist talk about for four days? Could anyone tell Teddy Roosevelt anything?

On May 14, 1903, a locomotive puffed into the Sierra foothills town of Raymond, California. From one car stepped the grizzled John Muir. Then, in rugged camping attire, came the president of the United States. Hundreds lining the platform cheered. Roosevelt said a few words, then the men climbed into a stagecoach.

They slept that night in Mariposa Grove. “Lying out at night under those giant Sequoias,” Roosevelt later told a crowd, “was like lying in a temple built by no hand of man, a temple grander than any human architect could by any possibility build.” The president was surprised at how little Muir knew about birds, but Muir knew every plant, every rock, every corner of Yosemite.

The next morning, Roosevelt asked Muir to show him “the real Yosemite.” He ordered Secret Service and press to stay behind. Accompanied only by two park rangers, Muir and Roosevelt disappeared into the backcountry. Camping near Glacier Point, they awoke in four inches of snow. They trudged up switchbacks, crossed passes, and looked down on El Capitan. They marveled at the mountains, the trees, the skies. And they talked and talked.

Once back in civilization, the men bid goodbye. They never saw each other again but they never forgot. “Both the Yosemite and the big trees were all that any human could desire,” Roosevelt wrote a friend. “John Muir is a delightful man.” And Muir remembered, “camping with the President was a remarkable experience. I fairly fell in love with him.”

A week after the trip, Roosevelt wrote his Secretary of the Interior. “I should like to have an extension of the forest reserves to include the California forests throughout the Mount Shasta region and its extensions.“ Another strenous climb had begun.

“Many rich men were stirred to hostility,” Roosevelt remembered, “and they used the Congressmen they controlled to assault us.” In 1907, Congress amended an agricultural bill, proposing to curb Roosevelt’s power to create national forests. Knowing he couldn’t veto the vital funding bill, TR asked for a list of all western timberlands eligible for protection. Before signing the bill, he preserved the entire list. Sixteen million acres.

Before he left the White House, Roosevelt designated 150 million acres of national forest, three times the total of previous presidents. By executive order, he created 18 national monuments, including Devil’s Tower, Chaco Canyon, the Grand Canyon, the Petrified Forest, and in 1908, the Muir Woods.

John Muir died on Christmas Eve in 1914. Roosevelt remembered him as “a dauntless soul, brimming over with friendliness and kindness.” But America itself still struggles to learn what the president said after coming out of Yosemite.

“We are not building this country of ours for a day. It is to last through the ages.”