THE CHICKEN WHO SAVED BASEBALL

Slow and ponderous, baseball in the 1970s seemed like a relic. Organ music. Scores of 2-1. 3-2. 1-0. Cavernous stadiums with just 10,000 fans. And Yogi Berra’s adage: “If fans don’t want to come out to the ball park, no one’s gonna stop ‘em.” Then in March 1974, a short, wiry college student put on a chicken suit.

The promotion was just a one-week gig handing out Easter eggs at the San Diego Zoo. “Godawful work,” Ted Giannoulas remembered. But a promoter for KGB-FM had dropped by San Diego State, looked around a room and said, “‘You, the short guy! You fit the costume best.’ No audition, no interview, I didn’t even have to fill out a job application.” The pay: $2 an hour.

Next came Opening Day for Giannoulas’ beloved San Diego Padres. “I’ll bet I could get in there free in this get up,” he thought, so he called the front office. “So long as you mention us on the radio,” someone said. Giannoulas’ Chicken spent Opening Day in the stands, cavorting with the small crowd. Soon he took the field and took over the game.

More than 17,000 performances later, Ted Giannoulas’ face has never been seen in public. His name is little-known. To the millions who have cheered him, he is simply The Chicken. But in beak and feathers, he “discovered a side of my personality I did not know existed, almost a Jekyll and Hyde thing.” And once let out of the stands, this masterful mime gave a stodgy old game just the jolt it needed.

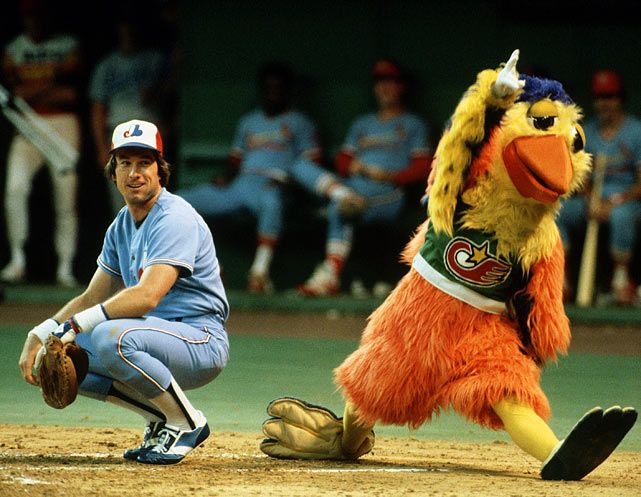

By mid-summer of ‘74, Padre attendance had doubled. Fans came not to see the last place team but to see the Chicken. Taking the field between innings, he chased umpires, then lifted one leg to wet on them. He ran the bases and slid head first. He wrestled players. He brought out a broom and battled groundskeepers, stole hoses and doused fans. He was pure joy in a chicken suit. He was just wonderful. Watch (and mute the silly music).

“The Chicken has the soul of a poet,” the San Diego Union wrote. “He is an embryonic Charles Chaplin in chicken feathers."

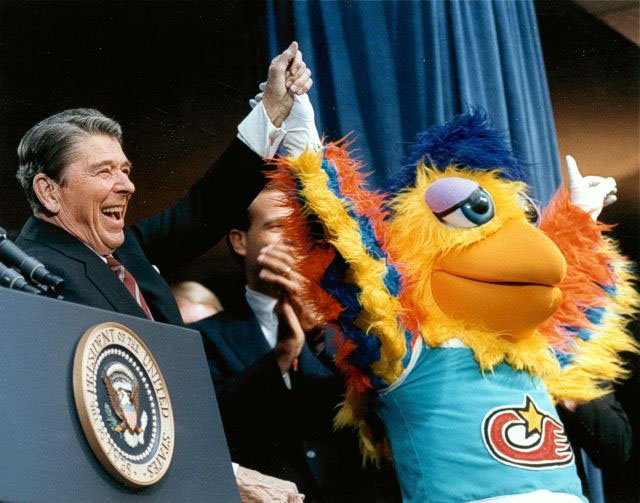

Soon the Chicken was showing up at NFL games, concerts, political rallies. But he still made every Padres game. The team’s attendance, once the league’s lowest, kept rising. Other teams noticed, and by 1979, most had mascots. A green Phillie Phanatic. A Braves Bleacher Creature. But none had the comic touch of The Chicken, who by then was costuming his costume. The Chicken was a greenish Statue of Liberty, a sunshine patriot with sunglasses and stars and stripes shirt, a Blues Brother in a black suit.

And then the Chicken disappeared.

Seems there was talk of merchandising the chicken image. But Giannoulas dreaded seeing his chicken as “a bunch of department store Santa Clauses nationwide.” KGB-FM got an injunction and Giannoulas went to court, testifying with a paper bag over his head. “If anyone in America was going to jail for wearing a chicken suit,” he said, “I wanted to be that guy.” The case went to the California Supreme Court. When the chicken won, San Diego held The Grand Hatching.

On June 29, 1979, before a sellout crowd, a motorcade of California Highway Patrolmen led an armored car through the centerfield gate. Atop the car was a huge styrofoam egg. To the theme from “2001,” Padres players lowered the egg onto the field. It rolled left. It rolled right. Then it split open. When the Chicken emerged, in a new suit, he got a ten-minute standing ovation. He was back.

The Chicken did not just save his career. He saved baseball. Drawn by the Chicken’s antics, families discovered the game. Organ music gave way to rock and disco with the Chicken dancing, strutting. Big screens replaced dull scoreboards and cozier parks replaced cookie cutter stadiums. Today an average game draws 27,000 and the atmosphere is energized. Friday nights at Fenway feel more like a singles bar than a ball game, but fans are happy. And baseball owes it all to a chicken.

Now 64, Giannoulas has cut back from 250 to 50 annual performances. “It’s not the end,” he said, “but I can see it coming.” Cavorting in a chicken suit, whose internal temperature can top 100, gets old. Still, he says, when the crowd roars, “the electricity just rips through your body.

Looking back, Giannoulas can’t quite believe his story. “As I started having some fun with the ridiculousness of it all, the days became weeks, the weeks turned into months. . . And to this day, I still don't have a real job. This really is a great country, you know.”