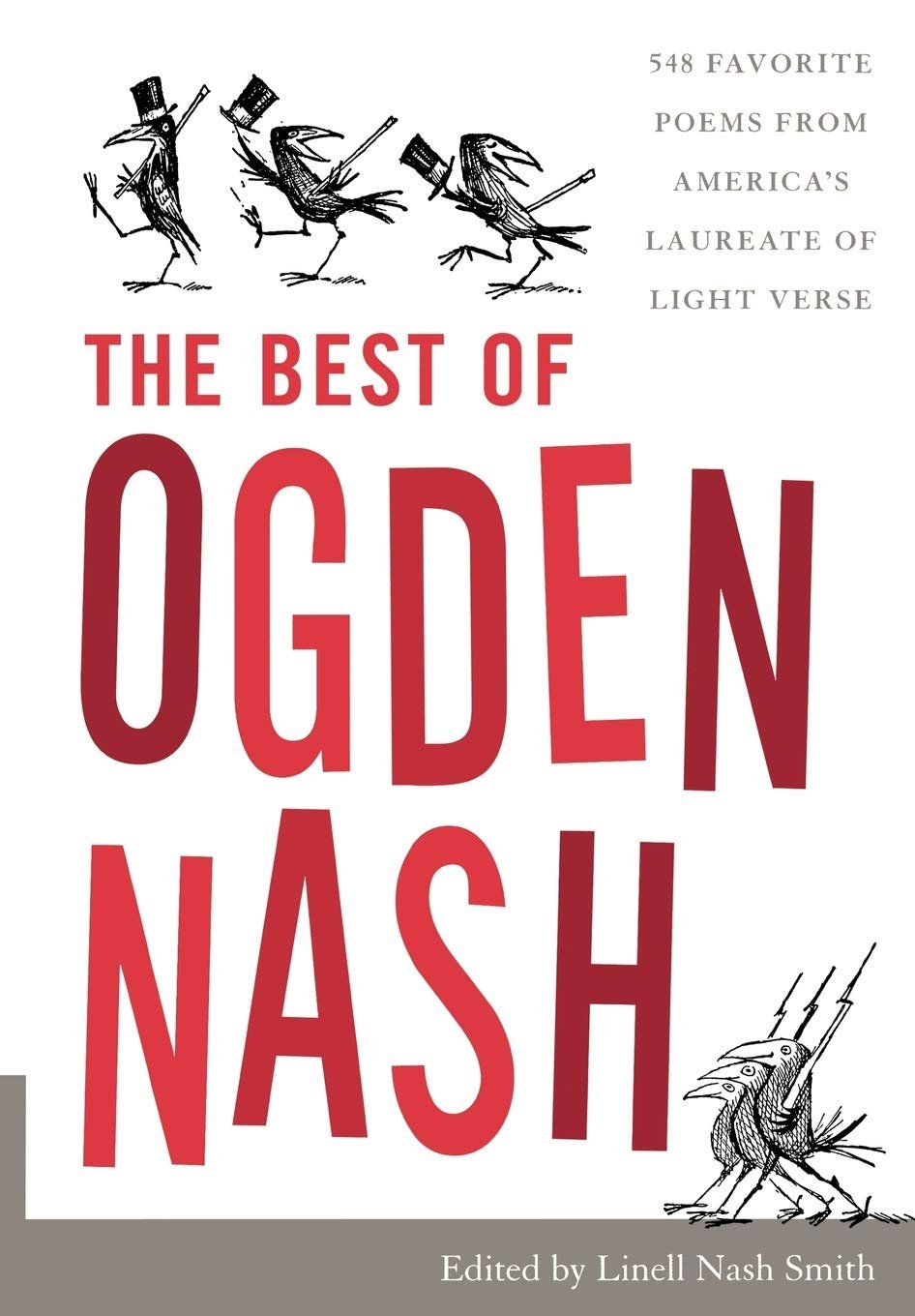

OGDEN NASH -- MASTER OF PACE AND RHYME

MANHATTAN, 1930 — On a breezy spring afternoon, a bookish, bespectacled editor looked out his office window in Manhattan. Forced by his job to consider “the most enormous quantity of bad poetry,” he had “a silly idea.” Bad poetry written “consciously instead of unconsciously,” might be “fairly amusing.” And so Ogden Nash began:

I sit in an office at 244 Madison Avenue

And say to myself, “You have a responsible job, havenue?”

Poets are a dour lot. “We Poets in our youth begin in gladness,” Wordsworth wrote, “But thereof come in the end despondency and madness.” Yet in life, as in verse, Ogden Nash mocked convention. He burst into American letters during the Depression, then lived a quiet life, teasing the English language into flights of fun that charmed everybody.

Some dismiss Nash as a mere wordsmith, yet W.H. Auden found him “one of the best poets in America.” Another fan, former poet laureate Billy Collins, said Nash had “the most essential of a poet’s credentials, a crazed affection for the language.” Nash came by his talent early.

“I think in terms of rhyme,” he said, “and have since I was six years old.”

Homeschooled, then prep-schooled, Nash ended up in Harvard. But in 1920, Manhattan was calling, so he dropped out to work on Wall Street, then for Doubleday, writing ads. Struggling to craft sonnets, like his idols Keats and Shelley, he lacked all talent for that “naked beauty stuff.” Then, after moving from ad man to editor, he began writing verse. When his avenue-havenue poem landed in The New Yorker, editors asked for more. Nash obliged with several couplets. One was “Reflections on Ice Breaking”:

Candy is dandy

but liquor is quicker.

New Yorker founder Harold Ross urged Nash to “write a lot more of these verses for us. They are about the most original stuff we have had lately.” A stint as a New Yorker staffer made Nash appreciate the freedom of freelance, and as in verse, his timing was perfect.

The Depression saw Americans turn for levity to the Marx Brothers, W.C. Fields, and Ogden Nash. During the 1930s, Nash published six best-selling collections of verse. One year, he had 48 poems in the Saturday Evening Post, 52 in the New York American, and 19 in the New Yorker.

Astonished to be “the bright boy of the moment,” Nash hobnobbed with Thurber, Benchley, and Dorothy Parker. But while their lives were messy, his was mundane. In person, he was polite, even dull. Yet each morning, seated with a pencil and a yellow legal pad, he went wild. Along with short couplets, he tortured standard meter, perfecting a style he likened to “a horse running up to a hurdle but you don't know when it'll jump.”

One thing I like less than most things is sitting in a dentist chair with my mouth wide open

And that I will never have to do it again is a hope that I am against hope hopen.

He also wrote limericks:

Asked a patient before appendectomy,

“What kind of a fee d’you expectomy?”

Said the doc, “If your pulse

Indicates the results,

Anything but a post-dated checktomy.”

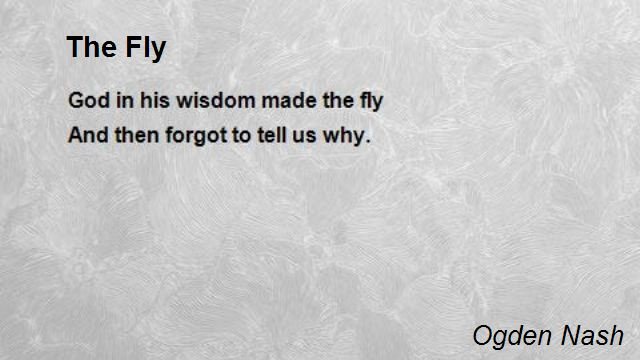

He described a menagerie of creatures – the llama, the oyster, even the termite:

Some primal termite knocked on wood

And tasted it and found it good

And that is why your cousin May

Fell through the parlor floor today.

Fatherhood gave him new subjects to play with.

Many an infant that screams like a calliope

Could be soothed by a little attention to its diope

And marriage’s many moods inspired. . .

And so it went for thirty-plus years. Seeking new outlets, Nash tried screenwriting. He failed, but worked briefly, without credit, on “The Wizard of Oz.” The rest of his life he lived in Baltimore, loved his wife Frances, and aised two daughters.

O adolescence, O adolescence

I wink before your incandescence.

During World War II, Nash hit Broadway, writing lyrics for one hit musical and two flops. In the 1950s, he became a TV game show panelist. As he aged, he suffered occasional depression but revived himself, as he revived us, with wit. Still, the trials of aging showed through.

This the city

Beyond the Woods

These are the streets

The old man paces

These are the crowds

That pass him by

This is the mist

That veils their faces,

These are the eyes

That do not include him

These are the voices

He cannot hear

These are the children

Who people the city

This is the old man—

And this is fear.

Age took him early. A kidney disease claimed him in 1971. He was 68. He left hundreds of poems, helping us laugh at life, death, children, marriage, and just about everything else. Even poets.

So my advice to mothers is if you are the mother of a poet don't gamble on the chance that future generations will crown him

Follow your original impulse and drown him.