ERIC HOFFER, LONGSHOREMAN FOR THE MASSES

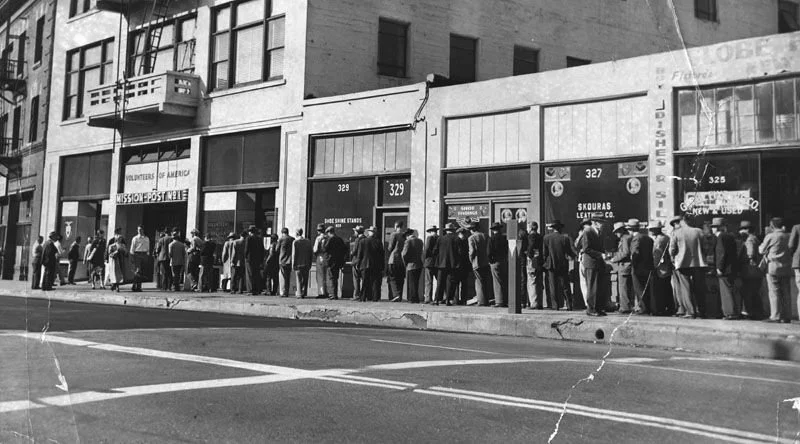

The 1950s was the decade of mass — mass thought, mass movements, mass media. Americans casually discussed “the lonely crowd” and “the organization man.” But one book saw the masses for what they were – disillusioned and desperate.

The True Believer was hailed as “brilliant and original.” The book captivated philosophers, political scientists, even presidents. Who was this insightful author? In what university did he teach? Finally, someone found him — on the docks of San Francisco, loading freight.

Eric Hoffer spoke with a gruff German accent, but he was an American original. He never traveled outside the country. Orphaned at eighteen, he “wandered up and down the land, dodging hunger and grieving over the world.” He pondered suicide, survived Skid Row, and worked as a field hand, dishwasher, longshoreman. Yet he kept his faith in America, and shared it.

Hoffer, said CBS’ newsman Eric Sevareid, “made millions of confused and troubled Americans feel very much better about their country. He showed them again the old truths about America and why they remain alive and valid.”

Most writers live for ideas but Eric Hoffer lived with them. He had no siblings, wife, or family. His sad but inspiring life made Hoffer himself a true believer— in truth.

Hoffer claimed he was born in the Bronx at the turn of the century, but there was no birth certificate, no census record. More certain was the signature moment in his childhood when his mother, carrying him down the stairs, fell. Elsa Hopper never recovered, dying two years later. Her son soon went blind.

For eight years, Hoffer lived deep inside his darkness. When he recovered his eyesight, fear of recurring blindness gave Hoffer, who never spent a day in school, an insatiable appetite for reading. A few years later, when his father died, Hoffer threw himself into America.

Throughout the 1920s, he lived in L.A., working odd jobs, living in tenements, reading, reading. From stacks of index cards scribbled with quotes, he culled his philosophy. During the Depression, he again hit the road, working in California’s vast farm fields. In every town where he picked crops, he had a library card.

“My writing is done in railroad yards while waiting for a freight,” he said, “in the fields while waiting for a truck, and at noon after lunch. Towns are too distracting.”

In 1938, Hoffer sent an article about tramps to a magazine. The magazine turned it down, but the editor kept in touch. A decade later, settled in San Francisco, Hoffer sent the woman a hand-written manuscript. She typed it, submitted it, and in 1951, The True Believer: Thoughts on the Nature of Mass Movements was published. Its author was a middle-aged longshoreman hailed by the New York Times as “a genius against insuperable odds, capable of amazing insights into history.”

So who was Hoffer’s True Believer? In the age of Hitler, Stalin, and Mao, he was the fresh convert to a cult of personality.

The true believer is everywhere on the march,” Hoffer wrote. But tyrants, he cautioned, do not rule solely by coercion. True believers surrender their independence because it has gotten them nowhere. Disillusioned and defeated, they follow promises of greatness en masse. Fascism. Communism. Nationalism. Believe. Join. Trust us.

“The less justified a man is in claiming excellence for his own self,” Hoffer wrote, “the more ready he is to claim all excellence for his nation, his religion, his race or his holy cause.” Hmmm.

The True Believer made Hoffer’s name but not much money. He published more books — The Passionate State of Mind, The Ordeal of Change — but kept his job on the docks. On into the 1960s, he walked daily in Golden Gate Park, stopping to write in notebooks. Living alone in a small flat with no phone, no TV, he courted ideas. “I get the longshoremen mad when I say, ‘You know, I can’t think of anything more exciting than going to bed with a half-finished paragraph.’”

Amidst growing acclaim, Hoffer taught classes at Berkeley and wrote a syndicated column. LBJ consulted with him. Journalists sought his opinions. Finally, in 1967, Hoffer quit working and withdrew from public life. 'I'm going to crawl back into my hole where I started,” he said. “I don't want to be a public person or anybody's spokesman. . . Any man can ride a train. Only a wise man knows when to get off.”

When Hoffer died in 1983, he left behind nine books and 100+ notebooks now at Stanford’s Hoover Institute. But he also left a unique understanding of charismatic leaders and the followers who trade reason for blind faith. True believers, it seems, are still on the march and the longshoreman-philosopher can help us understand them.

“Power corrupts the few, while weakness corrupts the many,” Hoffer wrote. “Hatred, malice, rudeness, intolerance, and suspicion are the faults of weakness.”