IMAGINATION IN A BOX -- THE MYSTERIES OF JOSEPH CORNELL

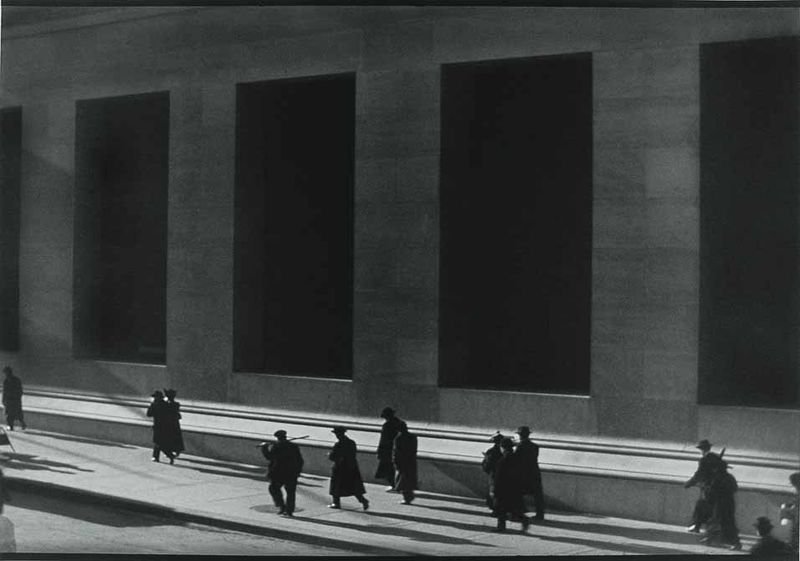

MANHATTAN — 1920S — Throughout the Lower East Side, antique merchants in Lower Manhattan start to see the same man haunting their stores. Tall and thin, he is alone, always alone. He never says a word, just browses and buys. Pillboxes. Compasses. Old wine glasses and pipes and dolls. Merchants find him annoying. Why doesn’t he talk? Say what he wants the junk for? But the tall, thin man does not live in this world. He lives in “Eterniday.”

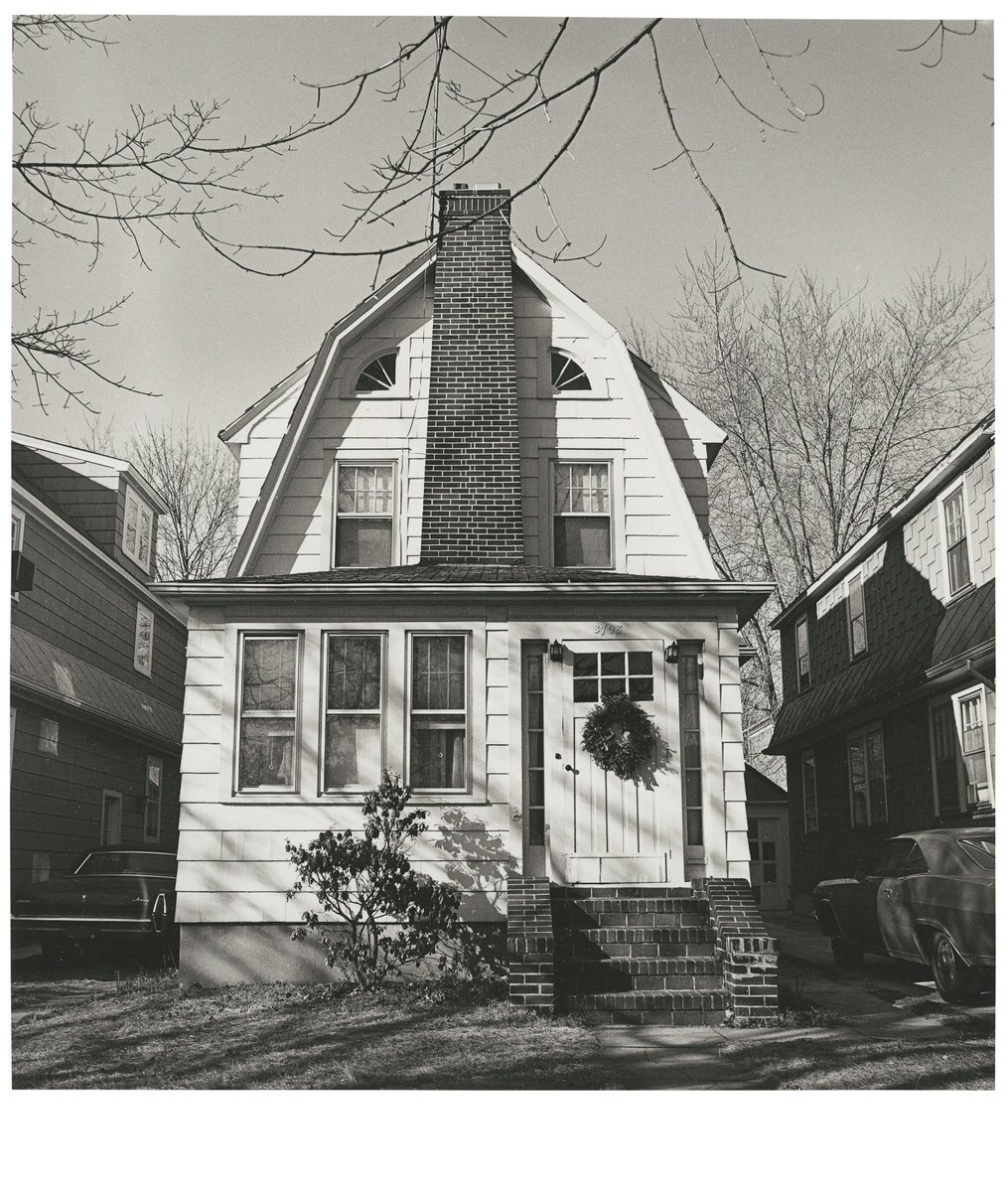

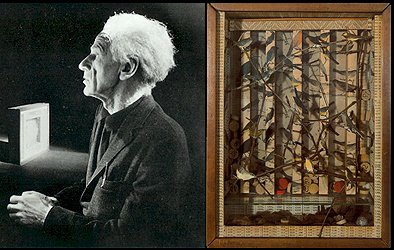

Joseph Cornell did not finish high school. He never took an art class. And while artists tehd to live in lofts and garrets, Cornell lived his entire life with his mother and younger brother. In a small house in Queens, on Utopia Parkway.

“There are fairy stories to be written for adults,” Surrealist Andre Breton wrote. “Stories that are still in a green state.” The life of Joseph Cornell is one of those stories. His works now sell for millions, but he did not make art for money. He worked to make “white magic,” and to capture his imagination in a box.

Cornell’s childhood, like his art, juxtaposed wonder and sadness. The oldest of four children, he remembered family visits to Manhattan, “feeling entranced by the lights.” He marveled at Coney Island, saw Houdini and Buffalo Bill. And then, when he was 13, the magic ended. His father died of leukemia, leaving a wife and four children. The youngest, Robert, had cerebral palsy.

Devoted to his brother, Joseph would spend the rest of his life caring for Robert and their mother. The duty began just after Cornell left prep school. Each morning throughout the 1920s, he took the subway from Queens to his job as a textile salesman. He hated the grind. The pressure gave him migraines, the hours wore him down. But Manhattan gave him a window on his childhood.

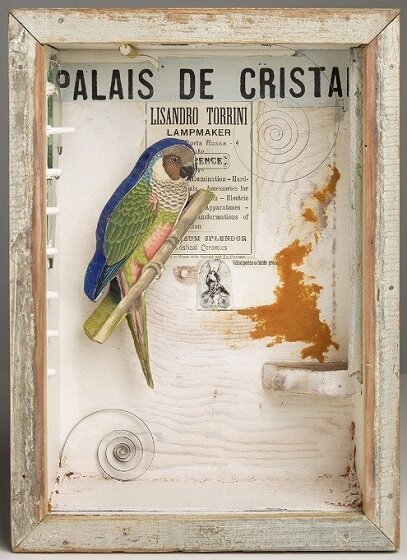

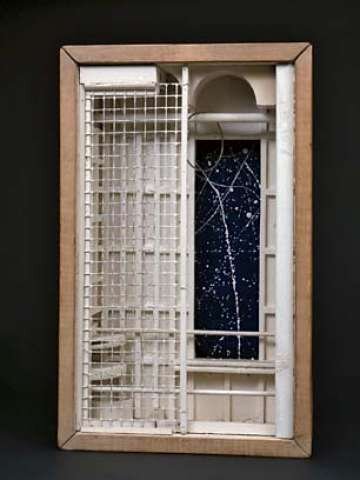

Afternoons and weekends, Cornell roamed 1920s New York. Rising skyscrapers. Reflecting windows. Stores filled with buttons, books, and bric-a-brac. Back home, Cornell assembled his junk into “dossiers” in a hundred different categories.

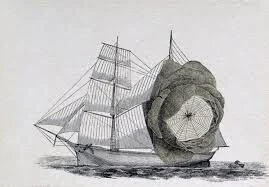

Inspired by the new art form called collage, Cornell made his first work in 1931 — a schooner with a spider web as a sail. He took this and another collage to a gallery where the owner had spotted him browsing. Within a month, he found his work entered in Manhattan’s first show of Surrealism.

Surrealism, n. — “psychic automatism in its pure state, by which one proposes to express the actual functioning of thought."

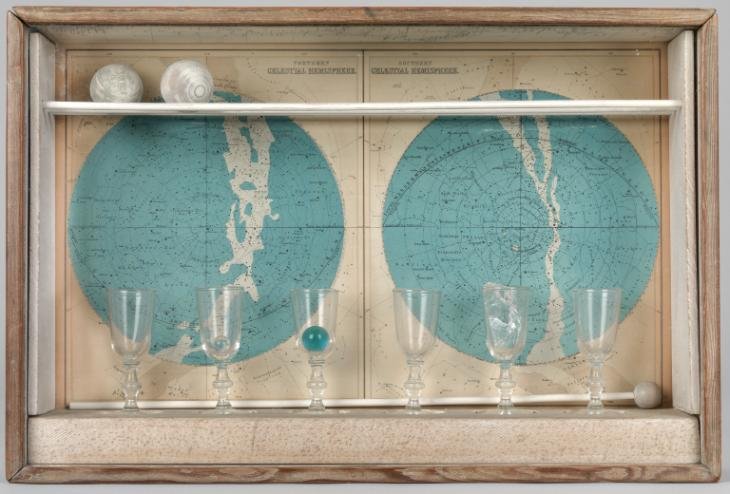

Laid off during the Depression, Cornell struggled to support his mother and brother. He sold refrigerators door-to-door. He worked in a nursery. And he roamed the streets, alone. He would never marry, never have a relationship. Instead, he poured his passion into boxes, starting with pillboxes he filled with beads and shells. By 1936, though his mother complained of the clutter, he was working each evening at the kitchen table making art like no one had ever seen.

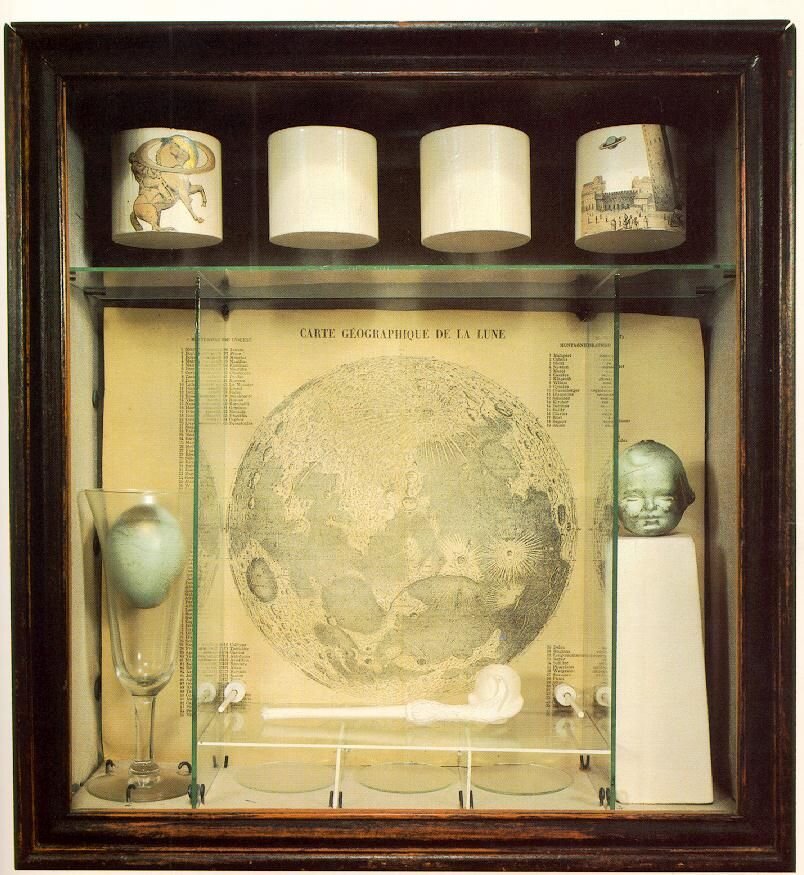

Critics and amateur analysts love to speculate on what a Cornell box “means.” The pipe is for his late father. The wine glass his mother. The four cups for Cornell and his siblings. . . Perhaps. but why not just stand back and wonder?

Cornell’s first boxes were soon displayed at the Museum of Modern Art. He befriended Salvador Dali and Marcel Duchamp. But while they traveled the art world from Paris to Manhattan, Joseph Cornell traveled to Eterniday — his word for the fusion of timeless images and daily life.

“Look at everything as though you were seeing it for the first time, with the eyes of a child fresh with wonder.”

Desperately lonely, he fell in love with Hollywood starlets — Garbo, Lauren Bacall, Hedy Lamarr. He put their pictures in boxes that he sent to them. Other boxes exalted childhood. His “Medici Slot Machines” set Renaissance princes and princesses beside stars, feathers,and wooden balls. He boxed the universe with images of the moon, comets, constellations. Living with life’s limits, he refused to limit his imagination.

By the 1940s, museum and gallery shows gave Cornell a name, and jobs designing magazine covers. He hobnobbed with artists and the women he found most fascinating — ballerinas. But he went home each night to Utopia Parkway, living there alone after his brother died in 1965, then his mother a year later.

“The mind of the dreaming man,” wrote Andre Breton, “is fully satisfied with whatever happens to it.”

Cornell had a major retrospective at the Met in 1970. Two years later, he died of heart failure. Since then the reputation of this lonely dreamer has only grown. In 2007, a New York Times critic observed: “Everything about him, from his fixation on childhood to his play with gender to his mix of fantasy and darkness to his outsider/insider allure, makes sense today. . . Many of the most interesting artists today are in his debt.”

Artists may be a dime a dozen now, their works filling whole basements in every museum. But there is only one artist who put the human mind, with all its hope and longing, into a box.

“Cornell was a voyager,” one critic wrote, “traveling through space and time in dimensions of the imagination and the spirit.”