THE OTHER COLUMBUS DAY

“We will be known forever by the tracks we leave.”

MINNEAPOLIS, OCTOBER 1992 — Five hundred years after he sailed the ocean blue, Columbus went on trial. The charges ranged from rape and murder to robbery and genocide. Dressed in the robes and tunics of 1492, speaking to an audience in the Minnesota State Capitol, the long-dead explorer had his day in court.

″He is a symbol of evil treachery, brutality and all that was bad in the world 500 years ago,″ the prosecution claimed. ″This is a person who deserves the condemnation of humanity.” But the defense countered that Columbus was a bold adventurer, a “deeply religious, upwardly mobile merchant mariner.” Called to testify, Columbus told the court he got along well with the “Indians” until they massacred many of his crew. Further testimony came from a robed Queen Isabella and several natives. Finally, the verdict.

Christopher Columbus of Genoa! The court finds you guilty of murder, torture, slavery, kidnapping, and robbery. Columbus was sentenced to 50 years of community service.

Since losing his court case, Columbus has lost another verdict— the verdict of history. Long hailed as the “Admiral of the Ocean Sea,” Columbus has been convicted in the court of public opinion. And the verdict has spawned celebrations nationwide.

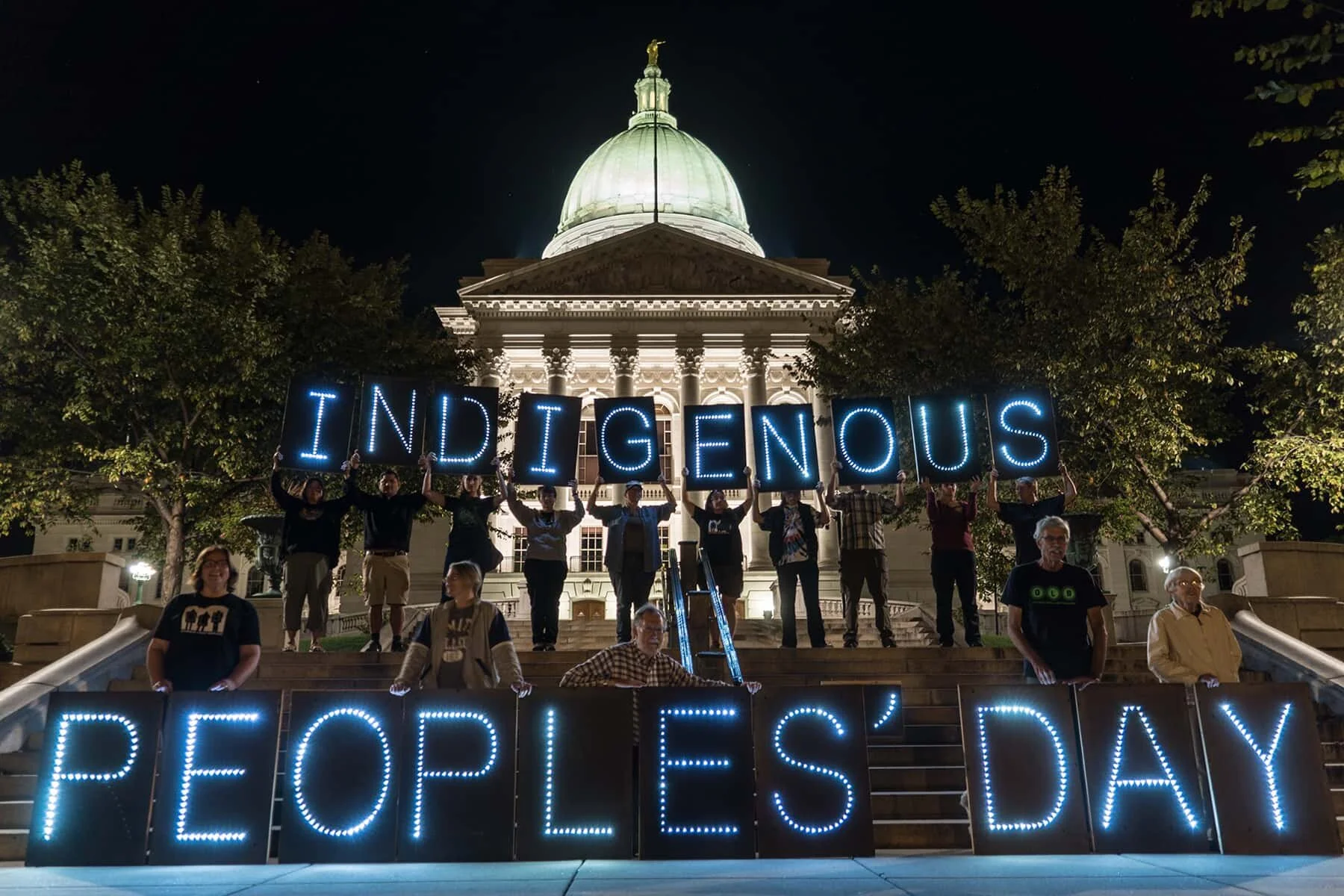

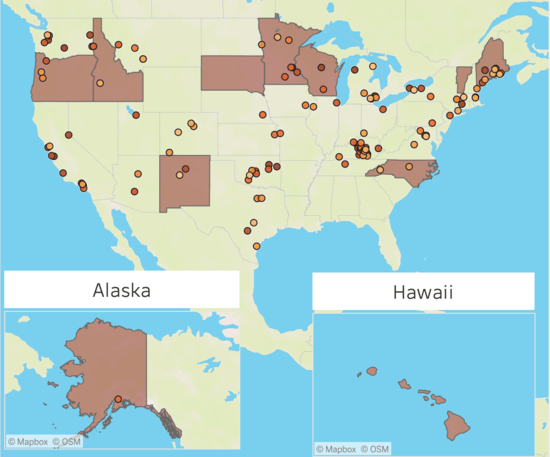

This year, on what used to be just Columbus Day, thirteen states and more than 100 cities will celebrate a different holiday. Hawaii calls October 12 Discoverers’ Day. South Dakota will hail Native-American Day. Other states and cities, from San Francisco to DC to Maine, will honor Indigenous People’s Day.

Though there will be fewer public ceremonies in this viral year, past celebrations involved parades, native dances, and eulogies to the people already here when Columbus “discovered the New World.” Despite occasional mention of the atrocities, which included all of the above crimes and worse, the festivities speak of revival rather than defeat.

“This change allows the opportunity to bring more awareness to the unique, rich history of this land that is inextricably tied to the first peoples of this country and predates the voyage of Christopher Columbus,” the National Congress of American Indians announced.

Like Columbus’ crew, dragged out of prisons and sent to sea, it behooves us to ask how we got here.

Time was when a heroic Columbus sailed through American history. The first Columbus Day celebration, held in New York in 1792, led to bold adventures set down in history books. Another huge celebration in 1892 handed Columbus’ legacy to newly arriving Italian-Americans. Soon the charge was taken up by the Knights of Columbus and all teachers in search of heroes.

During the Depression, FDR made Columbus Day a national holiday. Then came the Dueling Histories of the Sixties. Inspired by the Native-American siege of Alcatraz, the American Indian Movement began presenting the dark side of Columbus. How his men avenged the massacre. How he returned to govern Hispaniola, enslaving thousands and jumpstarting centuries of devastation — guns, germs, and steel — that followed his arrival.

Not everyone knows this side of the story, however. The spread of Indigenous People’s Day is a symbol of America’s divide. Even as states and cities celebrated, a poll showed that 56 percent of Americans still revere Columbus and his holiday. A survey of history texts found that the majority have not caught on to Columbus. How much do you want to tell children about severed hands and slaughtered peoples? Most texts, one study noted, still “see Indigenous Peoples as a long since forgotten episode in the country’s development.”

As the Navajo say, “You can’t wake a person who is pretending to be asleep.”

But the handwriting is on the wall, and on the remains of statues removed by vote or toppled in anger. Each year since 2014, dozens more cities have adopted Indigenous People’s Day. What started in college towns now includes celebrations in Dallas and Wichita, Salt Lake and Nashville. Kentucky has more local Indigenous Peoples’ Day celebrations than any other state.

If you can’t join a parade this year, the Smithsonian’s Museum of the American Indian recommends its online celebration. October 12 at 1 p.m. EST. And if you miss that one, check out the museum’s Native Knowledge 360°.

In Columbus’ wake, America’s native population fell from 60 million in 1492 to just a quarter million in 1900. And by 1900, Indian schools were teaching “white ways,” banning native languages and dress, in an effort to “kill the Indian and save the man in him.” But in the last half century, the resurgence of native pride has reclaimed the past. With native nations numbering 600 and their population topping 6 million, the final word will go to the Arapaho.

“If we wonder often, the gift of knowledge will come.”