THAT MAD, MAD MAGAZINE

During the coldest days of the Cold War growing up was a humorless task. Adults enjoyed mature wits — Mort Sahl, Lenny Bruce, Nichols and May — but kids were left with the usual Bozos.

Tom and Jerry just kept fighting. The Roadrunner beep-beeped. Captain Kangaroo wasn’t in it for the laughs. What was a Duck-and-Cover kid to do? And then from out of New York came a howl, a Bronx cheer, a magazine — MAD.

MAD, the New York Times wrote, “was magical, objective proof to kids that they weren't alone, that in New York City, if nowhere else, there were people who knew that there was something wrong, phony, and funny about a world of bomb shelters, brinkmanship and toothpaste smiles.”

Issue after issue, MAD did not disappoint. Here were send-ups of movies that truly stunk. Takeoffs of mindless commercials. Song parodies mocking the vast wasteland.

Summerti-ime, and the TV is disgusting

Shows are re-runs that were bad the first ti-iimmme.

As America’s class clown, MAD stood on the sidelines and mocked on. And a generation of wits, from underground cartoonists to SNL writers, honed their humor reading MAD. MAD’s message, said graphic novelist Art Spiegelman, was simple: “'The media is lying to you, and we are part of the media.' It was basically 'Think for yourselves, kids.'"

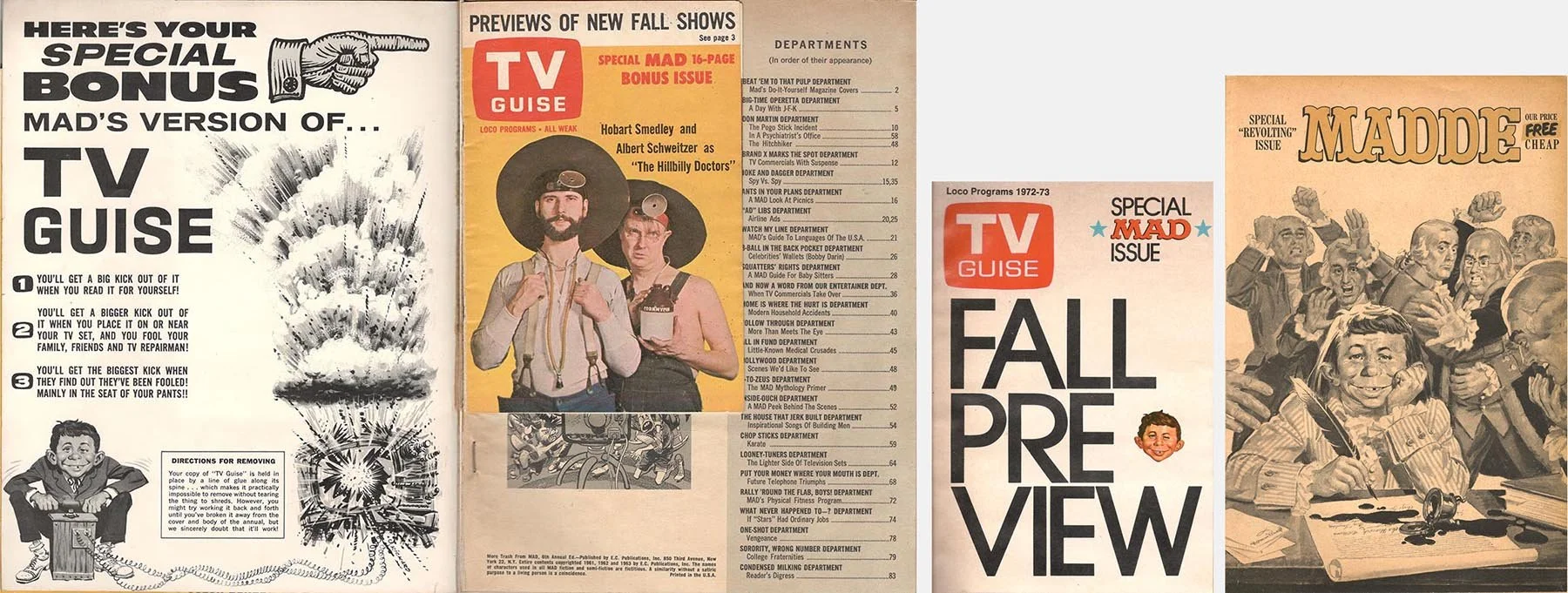

Started as a comic book in 1952, MAD soon morphed into a magazine. Early editions are collector’s items but sadly dated. It took a new editor, Al Feldstein, to give MAD its edge. By 1960, the magazine had a stable of writers, a.k.a. “the usual gang of idiots.” As mascot, they chose the gap-toothed Alfred E. Neuman. On every cover, Neuman’s “What, Me Worry?” grin contrasted with his wise epigrams heading each issue.

If communism is such a huge success, why don’t they put up a picture window instead of an Iron Curtain? — Alfred E. Neuman

Behind MAD’s madness was a singular wit — publisher William J. Gaines. Gaines was raised on comics. His father’s upstart comic line struck it rich with “Wonder Woman.” In starting MAD, Gaines had high standards. To keep material fresh, he limited issues to eight per year. He kept MAD merchandise to a minimum and published no ads.

“We long ago decided we couldn't take money from Pepsi-Cola and make fun of Coca-Cola.” Gaines treated his writers well, paying promptly, taking them on annual trips to Europe or the Caribbean. During one MAD trip to Haiti, Gaines learned that MAD had one subscriber there. Tracking him down, the entire gang of idiots showed up at his door.

Under Gaines sardonic eye, with satirists like Dick de Bartolo and the masterful caricaturist Mort Drucker, MAD soared through the Sixties. The highlights are still clever, still funny.

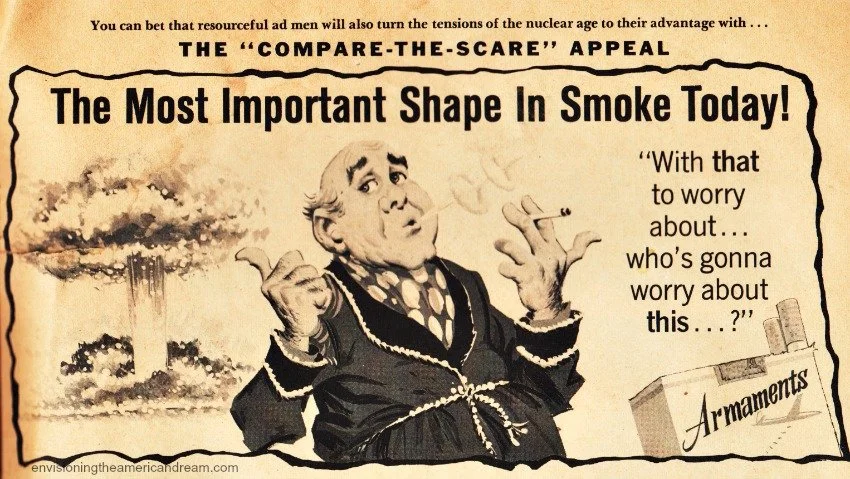

Through MAD’s lens “West Side Story” became “East Side Story,” with rival gangs — Castro and Khrushchev stalking JFK’s men — preparing a rumble at the U.N. “Movie Cliches We’d Like to See” turned Hollywood on its head. To wit: “Good news, Mrs. Johnson! Your horse survived that terrible fall. Of course, we had to shoot your poor husband.” MAD’s commercial parodies twisted slogans, imitated idiocy, even told the truth about smoking, “Lucky Strike separates the men from the boys. . . But not from the doctors!”

Some material got old. Every last issue had Dave Berg’s “The Lighter Side of. . .” and the tired Spy Vs. Spy. But at its best, novelist Joyce Carol Oates remembered, MAD was “wonderfully inventive, irresistibly irreverent, and intermittently ingenious." From MAD’s parody of TV Guide:

8:00 — 7 — DAKOTA — Western — North Dakota and South Dakota fight over which state this show is about. North Dakota wins the fight so the show is now called South Dakota.

Cynical Boomers made MAD their Bible. “I did not read the magazine,” said movie critic Roger Ebert. “I plundered it for clues to the universe.”

But as Boomers matured, MAD remained juvenile. Its target audience was that pimply age, 10-16, when childhood is fading, adulthood looms, and America’s incessant “Yes!” needs a skeptical “But!” MAD cartoonist Sergio Aragones: “People say ‘I used to read MAD, but MAD has changed a lot.' Excuse me— you grew up!”

Circulation peaked in 1973 at two million. Within a decade, it fell by two-thirds. Most of the “idiots” were still hard at play, but MAD’s success seeded its decline. Early readers created new satiric stages — National Lampoon, SNL, sketch comedy. MAD kept mocking, but William Gaines died, leaving MAD under control of Time-Warner. Ads appeared. Readership dwindled. When headquarters moved to L.A., none of the “idiots” went along. By 2017, MAD was no longer on newsstands Today, on website only, most articles are reprints.

Yet MAD’s spirit lives on in The Simpsons, The Onion, The Daily Show and its spinoffs. Like MAD during those coldest days of the Cold War, each speaks to the kid in all of us, the idealist who knows there must be more, more than this. Because:

Astronomers point out that star clusters, galaxies, in fact the whole universe is racing away from Earth at 15,000 miles per second. Can you blame it? — Alfred E. Neuman