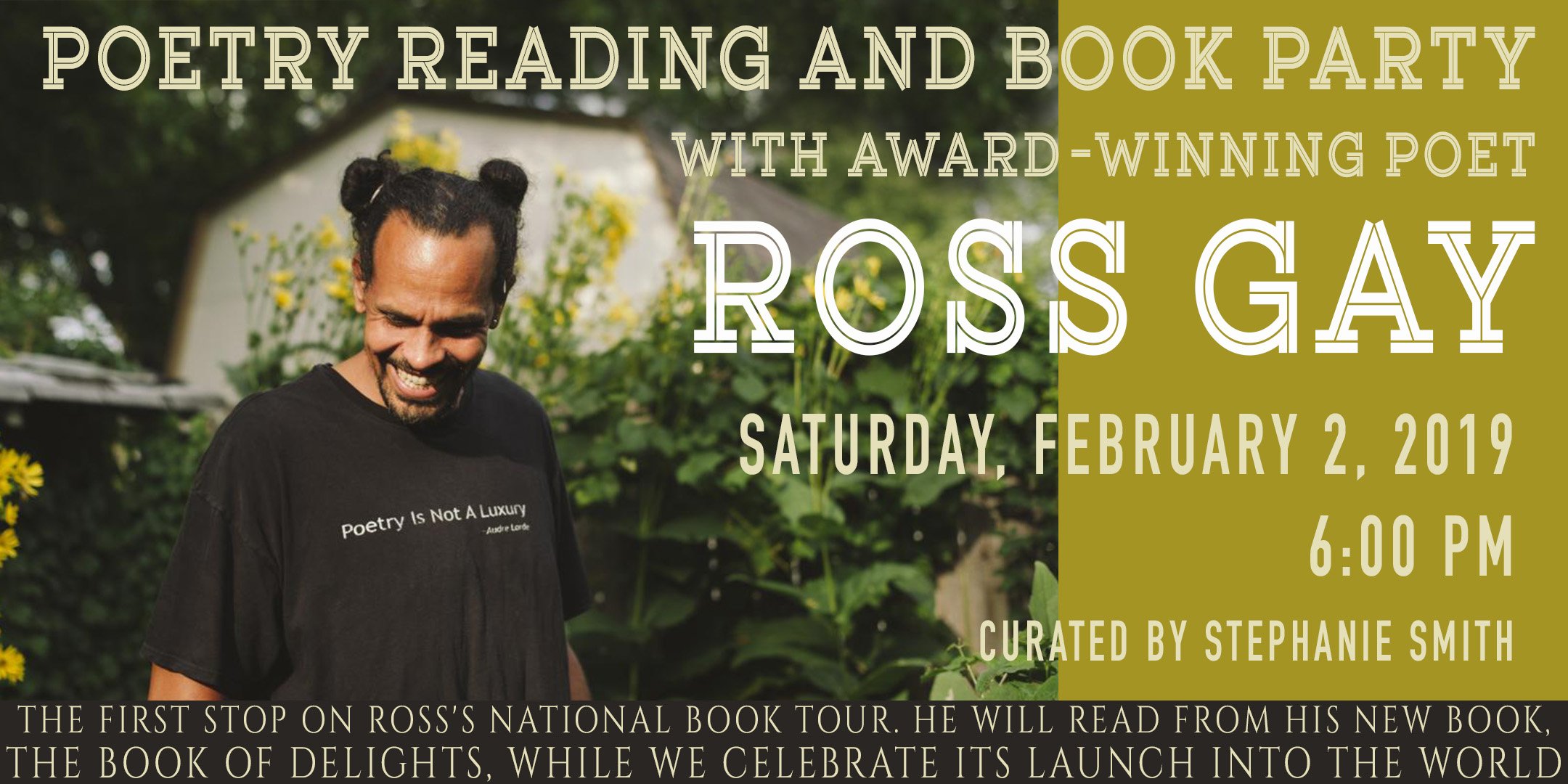

ROSS GAY, AMBASSADOR OF DELIGHT

July 2016 — a season of dread. Car bomb in Kabul. Wildfires in California. An ugly presidential campaign. But Ross Gay saw delight: “A field of sunflowers stretched to the horizon, casting their seedy grins to the sun above, the honeybees in the linden trees thick enough for me not only to hear but to feel in my body, the sun like a guiding hand on my back, saying everything is possible. Everything.”

Suddenly, Gay had a dazzling idea. Why not make delight a daily pursuit? Though a poet, he would write prose. In long hand. With a lavender pen. One essay every day for a year, about whatever delighted him. He would begin on his birthday.

The Book of Delights is not some Pollyanna project. Its 102 short essays roam freely across the American mindscape. And in that mindscape, Gay finds pain, promise, and above all, connection. He finds delight in his garden. In a purple scarf. In “a baby’s hand wrapping around my finger.” But mostly, he finds delight in us — in “the underground union between us, you and me, which is, among other things, the great fact of our life and the lives of everyone and thing we love going away.”

Ross Gay was well prepared to become the ambassador of delight. His father took him and his brother to a field to see fireflies. His mother fought tirelessly for her sons’ dignity and education. Against the assaults of racism and poverty, both kept family and lives together. Gay delights in “the hammer we kept under the seat to tap the stuck starter until it went completely kaput. A rectangle of sheet metal screwed into the rusted-out floorboard of the Corolla. A sheet of plywood tossed over the dinner table for holiday dinners. Taped glasses. Shoe goo. Duct taped car hood. Oh, I could go on.”

(READ EIGHT FROM THE BOOK OF DELIGHTS in Attic Lists)

Gay’s love of language took him from Levittown, PA to a Ph.D. In literature. Two books of poetry brought him acclaim, including a National Book Critics Circle Award. And his infectious spirit delighted students at Indiana University.

— “Ross Gay is AMAZING. If you ever have the chance to take a class from him, do it -- he is the most inspiring, caring, and talented professor that I've ever had,”

— “If you ever see his name pop up as an option, TAKE HIM OR YOU WILL REGRET IT!”

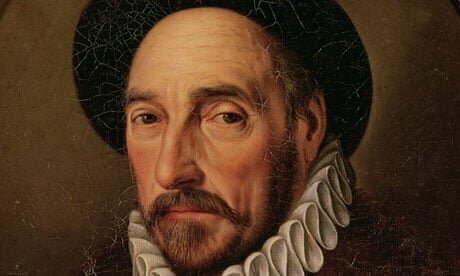

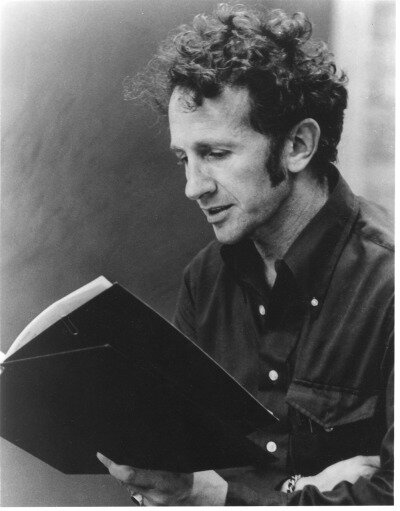

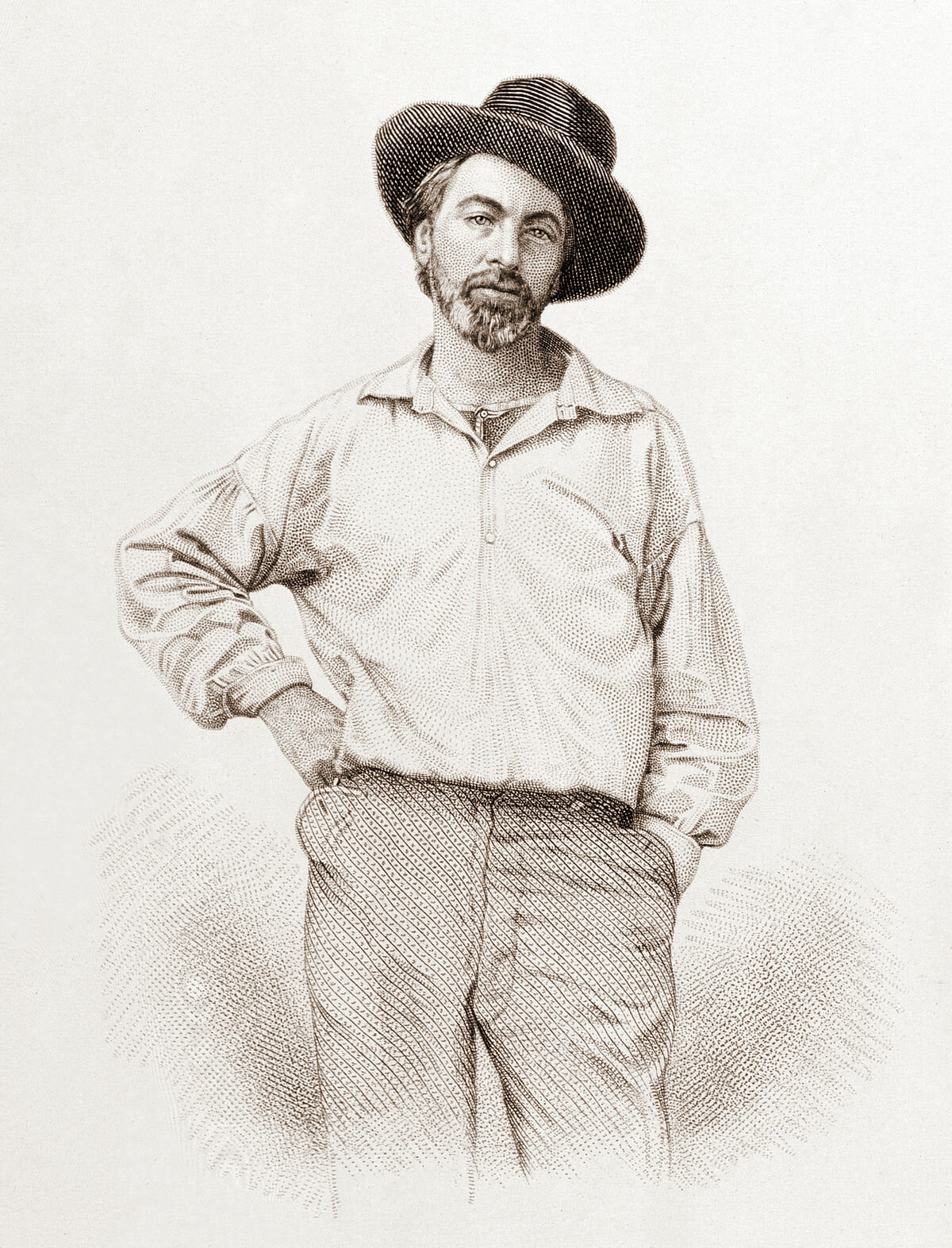

On August 1, 2016, his 42nd birthday, Gay told himself, “so your job for the year is to attend to your delight.” At first he worried about a “scarcity of delight,” but he soon saw joy wherever he looked. His “essayettes,” ranging from one to three pages, follow him around the country as he reads poems at festivals, schools, retirement homes. Whenever he takes out his lavender pen, delight thaws “the Siberia of my mind.” “My mother is often on my mind. Racism is often on my mind. Kindness is often on my mind. Politics. Pop music. Books. Dreams. Public space. My garden is often on my mind.” He quotes Montaigne, Philip Levine, Whitman, Zadie Smith. . .

But delight does not keep Gay from seeing sorrow, particularly “the inconceivable violence black people have endured in this country.” “All angels,” he notes, “remind us that annihilation is part of the program.” Rather than say “ta-daa — dee-light,” he told one interviewer, The Book of Delights “is about how do we attend to the ways that we make each other possible.”

On August 1, 2017, Gay finished his project. Eighteen months later, during another season of . . . oh, you know the drone, The Book of Delights was published. Critics took note. “Ross Gay’s eyes land upon wonder at every turn,” noted former poet laureate Tracy K. Smith. Gay’s prose, wrote the New York Review of Books, “feels as fluent and familiar as a chat with a close friend. . . you feel his hand on your arm, you feel him lean in toward you.” Recently, The Book of Delights reached the New York Times bestseller list.

We live in dark times. Agreed. But despair contains seeds of a better future, and Ross Gay is the perfect gardener — a poet, a teacher, a visionary — seeding your soul.

In his previous book Catalog of Unabashed Gratitude, Gay shares his joy with a child in a dream. But the child pushes back, saying the world will soon be over, that “it’s much worse than we think”:

“I said

no duh child in my dreams, what do you think

this singing and shuddering is,

what this screaming and reaching and dancing

and crying is, other than loving

what every second goes away?

Goodbye, I mean to say

And thank you, every day.”