LESLIE MARMON SILKO -- THE STRENGTH OF STORIES

LAGUNA PUEBLO, NM — Back in the heyday of TV Westerns, when kids played “cowboys and Indians,” a young girl in New Mexico was listening to stories. Her great-grandmother told her about Thought Woman, who created the world just by thinking. Other elders spoke of Coyote and Raven, and of ancestors from Ohio who married native women and settled on the high desert. Stories, stories. Leslie Marmon sensed their power.

When Marmon was a teenager, her father led a lawsuit against the state of New Mexico for taking land belonging to the Laguna people. Suddenly her house was filled elders who spoke no English but testified in court. “The old folks were going up against the state of New Mexico with only the stories,” she remembered.

The old folks won the lawsuit, but got just 25 cents an acre. And Leslie Marmon saw the limits of the law. A year in law school taught her still more about injustice. “I decided the only way to seek justice was through the power of the stories.”

Fifty years, three novels, and dozens of poems and stories later, Leslie Marmon Silko is a towering figure in Native-American literature. Her works, blending ancient myth with modern reality, have been hailed for their intricate originality. But for Silko, it all comes back to stories.

“Many people think of storytelling as something that is done at bedtime,” she said, “that it is something done for small children. But when I use the term storytelling, I”m talking about something much bigger than that.”

Leaving law school in 1970, Silko taught on the Navajo reservation, won a NEH grant, and published stories and a book of poetry, Laguna Woman. But when she married Alaska native John Silko, she found herself in an alien world. Her homeland had been a painted desert of ochre and adobe. Ketchikan, Alaska was a sopping seaport, foggy and green. Stranded far from the pueblo, raising two sons, with just rain and totem poles on her horizon, she turned back to stories.

“The literature of the aboriginal people of North America defines America.”

She had always wondered about the men who came home from World War II, back to the Laguna Pueblo near Albuquerque. Silent, bitter, they “stayed drunk the rest of their lives.” Now, a world away, Silko began a novel. Alaska was cold, forbidding. Her son was hospitalized with asthma. A visiting aunt had a heart attack. Seeking some “magic vehicle back to the Southwest land of sandstone mesas, blue sky, and sun,” Silko became Thought Woman.

Ts’its’tsi’nako, Thought Woman,

is sitting in her room

and whatever she thinks about

appears. . .

She is sitting in her room

thinking of a story now

I’m telling you the story

she is thinking.

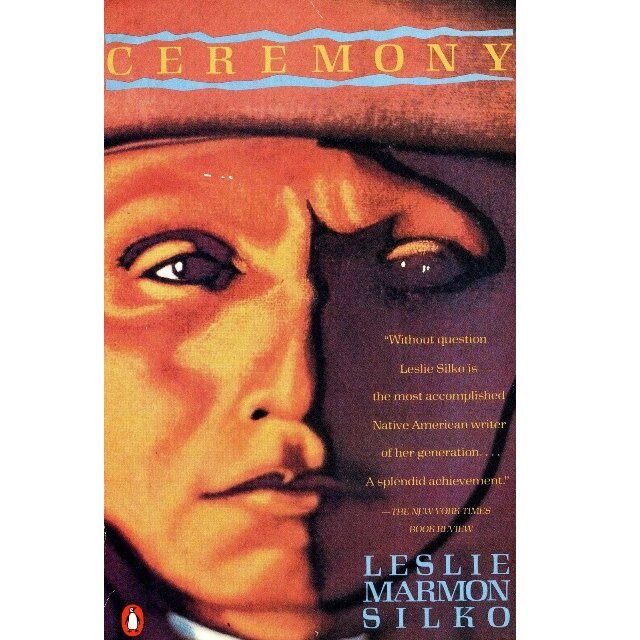

Silko’s story tells of a Laguna man, Tayo, home from the war. His only stories are horror stories — of the Bataan Death March and bodies washing up in memory. Only when Tayo returns to timeless stories does he recover, healed by ancient myths of ancestors and endurance. “Through stories,” Silko says, “we hear who we are.”

Published in 1977, Ceremony touched a nerve. In the wake of Vietnam, America and its vets were learning about post-traumatic stress disorder. And fueled by the native takeover of Alcatraz, the American Indian Movement was rising. Critics saw a literary “Native-American Renaissance,” with Ceremony as one seed.

Silko was hailed as “the most accomplished Native American writer of her generation.” Kiowa novelist N. Scott Momaday thought Ceremony so true that it should not be called a novel, but “a telling.” And in 1981, Silko won one of the first MacArthur Genius grants.

From there, Silko’s own story twists and turns. Divorced, relocated to the hills near Tucson, she spent ten years on her next novel. Almanac of the Dead weaves dozens of characters, timelines, and plotlines, all stretching to 700 pages. Silko knew she was breaking rules, “but this other notion took over—and I couldn't tell you rationally why. I knew it was about time and about old notions of history, and about narrative being alive."

Almanac of the Dead, the New York Times wrote, “burns at an apocalyptic pitch—passionate indictment, defiant augury, bravura storytelling." The New Republic called the book “one of the most ambitious literary undertakings of the past quarter century.” And Leslie Marmon Silko moved on — to essays, a memoir, and, at 76, an elder’s status as storyteller.

Ever since she was a girl in New Mexico, Silko has cherished her time in the hills. Alone with her imagination. Alone with rocks and trees and stories. “I never feel lonely when I walk alone in the hills. I am surrounded with living beings, with these sandstone ridges and lava rock hills full of life.”

Sunrise,

accept this offering

Sunrise.