THE BICYCLE THAT FLEW THE CHANNEL

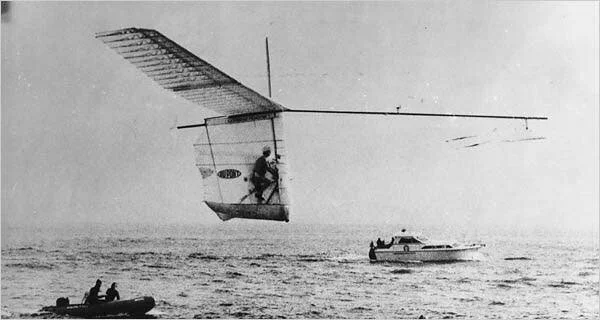

ENGLISH CHANNEL — JUNE 12, 1979 — Carrying no engine, no gas, the featherweight plane took off at dawn. To his left, the cyclist saw the white cliffs of Dover. Ahead stretched only sea and sky. The Gossamer Albatross was on its way. Destination: France.

Ever since those mythological Greeks, Daedalus and Icarus, fashioned wings of wax, human-powered flight had been a lofty dream. You’ve seen the footage. Flapping wings flumping to the ground. Multi-layered planes collapsing like a house of cards. But the Gossamer Albatross had more than legs to fly on. It was also powered by genius.

Seconds after takeoff, cyclist Bryan Allen feels “as if I have emerged from a world of black-and-white dreams into full-color reality.” For the next two hours, Allen must pedal at 80-90 rpm, follow directions from his support crew, and keep his lead boat in sight. The lead boat is the key. It carries the genius.

Like millions of kids, Paul MacCready loved model airplanes. “Anyone who's not interested in model airplanes,” he said, “must have a screw loose somewhere.” During World War II, MacCready trained as a Navy pilot, then earned a Ph.D. in aeronautical engineering from Cal Tech. In the 1950s, he took to the air, soaring in gliders above the California desert.

MacCready won national and world soaring titles, thanks to his MacCready Speed Ring. Glider pilots still use the invention which calculates the ideal speed for prolonged, powerless flight. So MacCready, busy gliding and designing, barely noticed when British industrialist Henry Kremer offered a prize — £50,000 — to the first Icarus to fly, self-powered, a one-mile figure-eight.

Designers began testing the limits of lightness and power. Planes slid down ramps or launched from catapults. Some flew a quarter-mile, half, three-quarters. . . But turning was tricky and gravity prevailed. Then in 1975, MacCready found himself in debt. “The prize equaled the debt!” he remembered. “Human-powered flight suddenly became attractive.”

Twenty minutes in, the Gossamer Albatross is faltering. Strong winds. The pilot’s breath fogging the cockpit window. MacCready radios back — stronger winds ahead. “It’s no use,” Bryan Allen thinks. “I’ll have to ditch.” Fondly, he recalls the Gossamer Condor.

The Gossamer Condor was MacCready’s first Daedalus design. Before starting, MacCready studied hawks and turkey vultures, marveling at their soaring feats. Applying his Ph.D., he calculated wingspan, wind speed, turning angles. Then, “pretending I never saw an airplane before,” he masterminded a craft that was part bicycle, part glider, with a touch of magic.

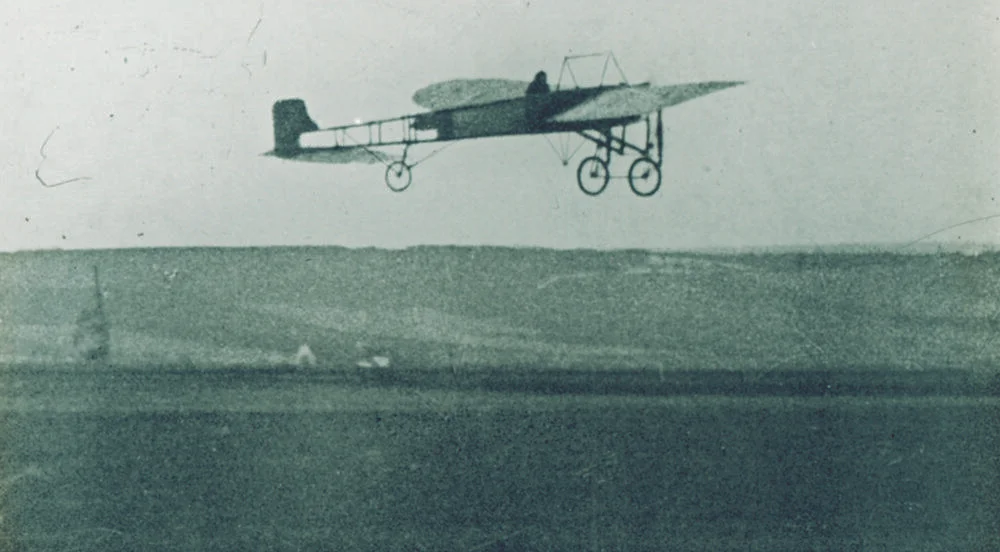

Wings stretched 90+ feet, longer than a DC 9’s. The cockpit was stripped— no door, barely a seat, a plastic chain hooked to a plastic propeller. With carbon fiber tubing and Kevlar coating, the Gossamer Condor weighed just 70 pounds. In 1977, Bryan Allen easily steered the craft around the figure-eight, then cleared a 10-foot bar at the finish, winning MacCready the Kremer Prize.

6:20 a.m. Inches above the water, Bryan Allen signals his crew. He is finished. Spent. But he must climb a little so the crew can hook the wings. Allen sprints to 15 feet. At that exalted height, there is less wind, no turbulence. “I’ll try it up here for a while!” he shouts down. And on he flies.

Days after the Gossamer Condor paid his debt, Paul MacCready learned of a new Kremer prize — £100,000. Back in 1909, a French pilot made a historic flight across the English Channel. Twenty-five miles! Could it be done on human power?

MacReady went back to the drawing board to design the Gossamer Albatross. In June 1979, his team disassembled the new marvel, shipped each piece to England, then rebuilt on the coast. Testing. Training. Weather checks. Plane and pilot were ready. But more trouble lay ahead.

6:30 a.m. Through his fogged window, Bryan Allen thinks he sees the coast. It’s only a supertanker. His water almost gone, he pedals on. Twenty minutes later, MacReady reports: “We have France in sight. Four miles to go.” But Allen’s legs are cramping. “Altitude six inches! Six inches!” Allen digs in, thinking “Against all hope! Against all hope!”

7:30 a.m. “Gossamer Albatross,” MacCready radios. “You have one mile to touchdown!” Seconds later, a crewman below calls out, “Fly into the sun.” Allen chuckles. He is Daedalus, not Icarus. No danger of flying too high. “Correction,” the crewman barks. “Fly towards the sun.”

Coming in on wings of carbon and Kevlar, the Gossamer Albatross skims the rocks along the shore. The propeller coasts to a stop. Winds settle and the plane lands softly on the beach. The exhausted pilot punches through the plastic. Champagne and roses. Hugs from the team and the genius. “Take the rest of the day off,” MacCready tells his human engine.

Paul MacCready went on to design prize winning solar planes and a solar car that crossed the Australian outback. MacCready earned dozens of prizes for aviation and creativity, and was one of TIME’s 100 Greatest Minds of the Century, but he never missed an opportunity to speak to young tinkerers.

Turn away from those screens, he advised. Keep your eyes on nature, which has already solved most design problems. And keep dreaming. “The only big ideas I ever came up with arose from daydreaming.”