GARY SNYDER -- THE POET WHO OUTGREW THE BEATS

The scene lives on in legend. The Six Gallery, San Francisco, October 1955. Five poets, the handbill says. “Remarkable collection of angels all gathered at once in the same spot. No charge. Small collection for wine and postcards. Charming event.“

And there is Kerouac sharing jugs of wine, everyone drinking, digging the first three poets. Then comes Ginsberg, short, bespectacled, suit and tie. “I saw the best minds of my generation. . .” And soon the gallery is exploding. Ginsberg chanting. Kerouac shouting “Go! Go!” And “Howl!” — raw and angelic — enters ‘50s America like a seed. But who’s next? Who can follow THAT?

Up steps a slim man with a goatee and blue jeans. His poem is something about Coyote and Bear and a “Berry Feast.” Few remember it. But when the poet goes camping with Kerouac, another Beat legend is born.

The Beats blazed like a meteor across the literary scene, but the blue jean poet who had to follow “Howl!” took a different path. Leaving America shortly after being present at the creation, Gary Snyder stepped from Beatdom into a poetics all his own.

Snyder is “the poet laureate of deep ecology.” With his unique blend of Zen Buddhism, working class tales, and Native-American myth, Snyder taught an entire generation to live closer to the land. “Snyder’s sane housekeeping principles desperately need to become government and corporate policy,” one critic wrote. “He is on the side of the gods.”

Gary Snyder seemed born to this. Raised near Seattle and later, Portland, he tended animals on his parents’ farm until, at age seven, an accident landed him in bed. His mother brought books. “I figure that accident changed my life,” he said. “At the end of four months, I had read more than most kids do by the time they're 18. And I didn't stop.”

Drawn to wilderness, he climbed Mount St. Helens at age 15, Mount Hood two years later. Working on native reservations, he was enchanted by myth and folklore. Equally enthralled with Chinese culture, in 1952 he went to UC Berkeley to study Oriental languages. There he was spotted by neighbors.

“Gee, he’s strange,” Alvah Goldbrook (Ginsberg) says in Kerouac’s The Dharma Bums. But this “Japhy Ryder” envisions a cultural shift, “a world of rucksack wanderers, Dharma Bums refusing to subscribe to the general demand that they consume production and therefore have to work for the privilege of consuming, all that crap they didn’t really want anyway.”

Snyder got a kick out of the Beats but soon tired of their “kicks.” “Being high all the time leads nowhere because it lacks intellect, will, and compassion.” So while the Beats hung around San Francisco, Snyder split for Japan. For the next dozen years, he lived as Japhy Ryder would — roaming, meditating, studying. He considered becoming a Zen monk but concluded “that I am firstmost a poet, doomed to be shamelessly silly, undignified, curious. . .”

When he finally settled in America, the counterculture was in full flower. Wanting no part of Beat fame, Snyder headed for the hills. In a modest home he built in the Sierra foothills, Snyder began living like the Chinese poet Han Shan, whose work he translated. Up in the morning to meditate, write, hike. A wife, two sons, no electricity, no running water. Then in 1974 came Turtle Island.

This, a critic noted, was “no hippie-dippy, feather-wearing poem. It was a manifesto, and the national environmental movement had to take it seriously.” With its call to simplicity and “bio-regionalism” — tending your own backyard instead of saving the whole planet — Turtle Island won a Pulitzer and made Snyder a spokesman for the earth. He spoke at UN conferences, at green gatherings, and at UC Davis, as a professor.

In The Dharma Bums, Kerouac idolizes Japhy but wonders “what will happen to him in the end.” He shouldn’t have worried. Snyder still lives in his Sierra home, one of those “Zen Lunatics,” Japhy descibes, “who go about writing poems that happen to appear in their heads for no reason.” Going out nights with a Thermos of sake and a star chart to check on the constellations. Appreciating “the world, in its nakedness, which is fundamental for all of us — birth, love, death, the sheer fact of being alive.”

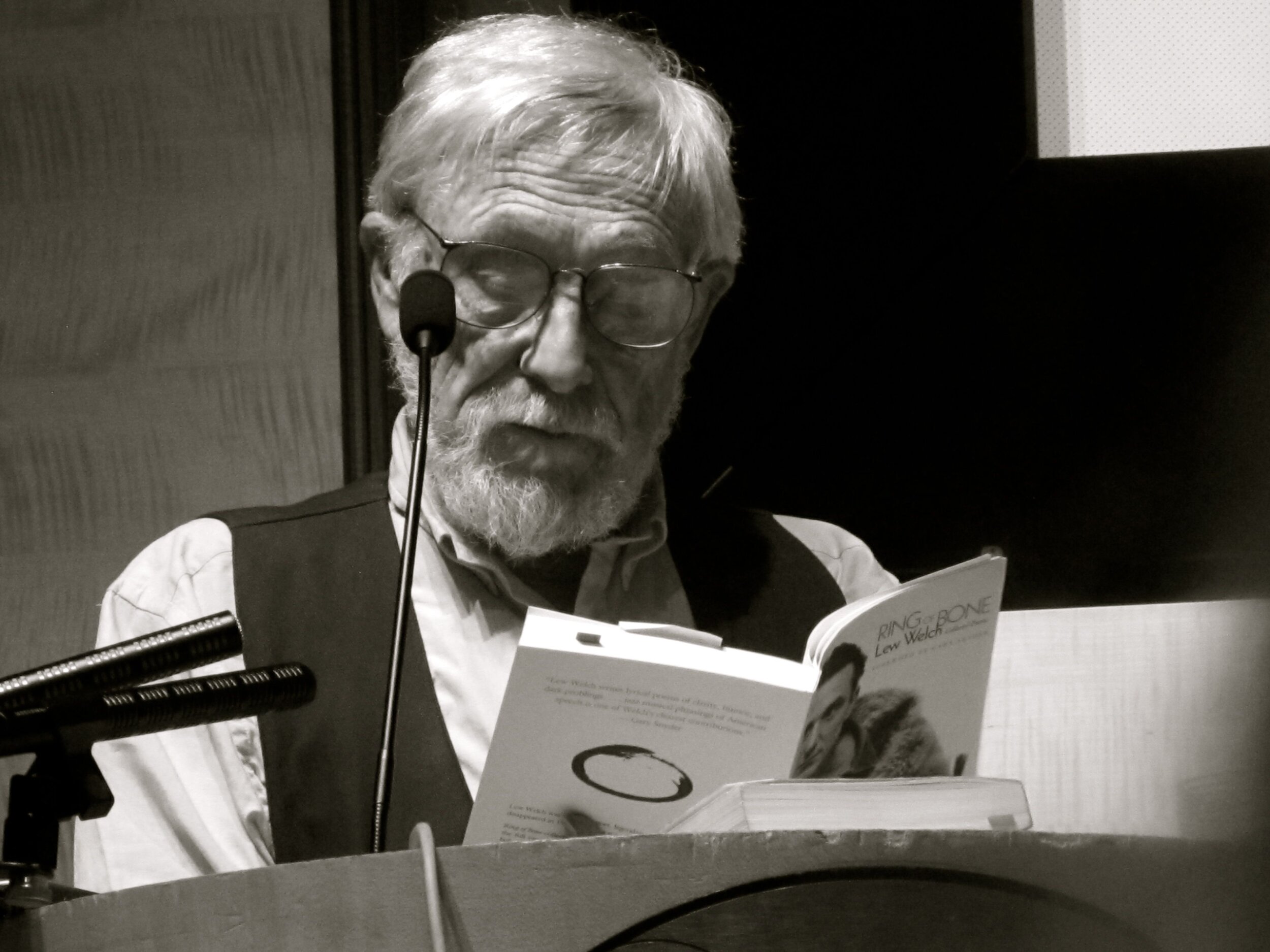

At 91, with a face like some craggy mountain, Gary Snyder sees us doing what he recommended long ago. Bringing our own bags to the grocery store, using natural fertilizer, recycling, carpooling. Noting the planet’s troubles, however, he finds it “not particularly gratifying to have been right.”

His work “such as it is, is done,” But he continues to teach in words that, even today, will be read for the first time by someone. In “Axe Handles,” he writes of teaching his son:

And I see: Pound was an axe,

Chen was an axe, I am an axe

And my son a handle, soon

To be shaping again, model

And tool, craft of culture,

How we go on.