OCTAVIA BUTLER -- SCI FI, SLAVERY, AND SEEDS OF THE FUTURE

READ “OCTAVIA BUTLER’S “FOUR TIPS FOR PREDICTING THE FUTURE” IN ATTIC LISTS

The 1950s was the golden age of sci-fi shlock. Sure, you could read Ray Bradbury or Isaac Asimov, but for every book sold, thousands watched B-movie dreck. “Cat Women of the Moon.” “Plan 9 From Outer Space.” “Attack of the 50 Foot Woman.” The future looked. . . weird.

One day while watching “Devil Girl from Mars,” ten-year-old Octavia Butler had “a series of revelations. The first was that ‘Geez, I can write a better story than that.’ And then I thought, ‘Gee, anybody can write a better story than that.’ And my third thought was the clincher: ‘Somebody got paid for writing that awful story.’”

Her father shined shoes. Her mother was a maid. But when Octavia got her first typewriter, the future looked. . . promising. There was, however, a glitch in the launch sequence.

Shy, awkward, convinced she was “ugly and stupid,” Octavia holed up in the Pasadena Central Library, reading science fiction. Transported to other planets, other galaxies, she did not see herself. A girl. A black girl. So when an aunt told her, “Honey, Negroes can’t be writers,” Octavia vowed to “write myself in.”

Twelve novels, dozens of stories, and a MacArthur Genius grant later, Octavia Butler’s reputation is soaring. Beyond other worlds, she is known for her eery predictions about Planet Earth.

“I began writing about power because I had so little.”

Decades ago, Butler foresaw the 2020s. “People have changed the climate of the world,” she wrote in Parable of the Sower. “Now they’re waiting for the old days to come back.” Some wear “dream masks,” others tune in “news bullets.” But it gets eerier when a presidential candidate runs on the slogan “Make America Great Again.”

“For sheer peculiar prescience,” the New Yorker noted, “Butler’s novel and its sequel may be unmatched.”

So how did a black girl write herself into a genre of white male techno-fantasy? By refusing to quit. “I shall be a best-selling writer,” Butler wrote in her journal. “So be it. See to it.”

After graduating from Pasadena City College in 1968, Butler joined writing workshops where she met sci-fi legend Harlan Ellison. When he published one of her stories, she felt “on my way, but I had five more years of rejection slips and horrible little jobs ahead of me before I sold another word.“

Rising at 2:00 a.m. to write, toiling all day, facing down the future, Butler pressed on. Then she remembered something overheard during the Black Power Movement. African-Americans, even slaves, should be condemned, a friend said, for surrendering power to whites. The man knew his history, Butler realized, “but he didn’t feel it in his gut.” Could science fiction, where “there are no closed doors,” plunge readers into the nightmare of slavery?

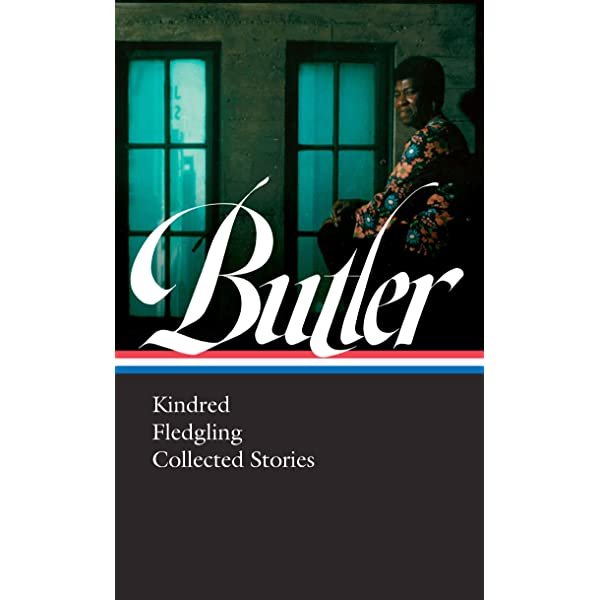

Her first novel had sold modestly. Another followed. Then in 1979, Butler published Kindred. The story sends Dana, a black writer in LA, whirling back in time to the ante-bellum South. All the whippings, all the degradation, all the hopelessness unfold. Readers feel slavery “in their gut.” “One cannot finish Kindred without feeling changed,” a critic wrote. “It is a shattering work of art.”

Butler soon penned fantastic stories that won Hugos and Nebulas, but as a “news junkie,” she could not escape the headlines. Global warming. Persistent racism. Technology distracting, distorting minds. Rather than dream of escape, Butler asked “what if this continues?”

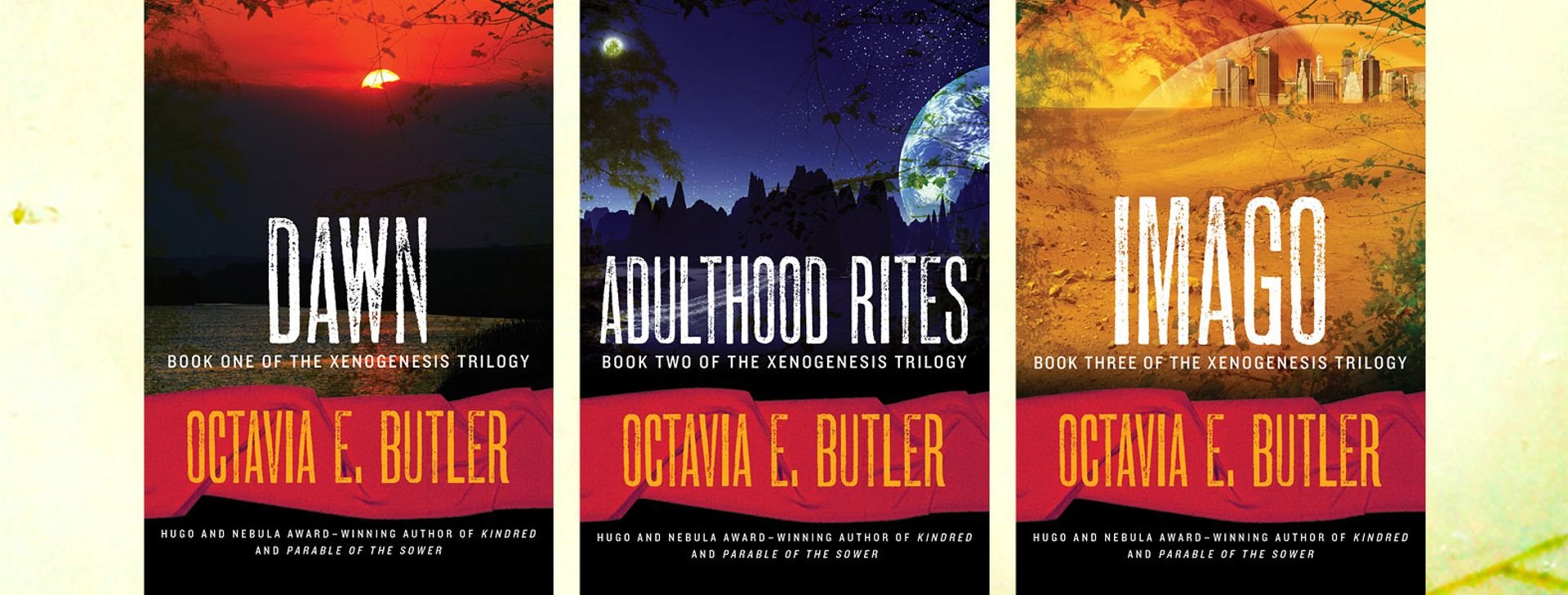

Her Xenogenesis Trilogy described a society doomed by divisions of race and class. Parable of the Sower envisioned a burning planet torn apart by inequality and greed. Hope emerges in a new religion, Earthseed, and a colony to spread the seed into the galaxy. The sequel, Parable of the Talents, left Butler so depressed she could not write.

A third parable book was never finished, but before she died of a stroke in 2006, Octavia Butler had written herself into the canon. Her novels, selling a million copies in 10 languages, have been adapted as opera, graphic novel, and podcast. Movies are in the works. Her name now graces an asteroid and a planetary moon, but her lasting legacy is in the headlines. The future has caught up to Butler’s fears, but it doesn’t have to end in defeat.

One afternoon, Butler was signing books when a young man approached.

“So do you really believe that in the future we’re going to have the kind of trouble you write about in your books?

“I didn’t make up the problems,” Butler replied. “All I did was look around at the problems we’re neglecting now and give them about 30 years to grow into full-fledged disasters.’

“So what’s the answer?”

“There isn’t one,”

“No answer? You mean we’re just doomed?”

“No,” Butler replied. “I mean there’s no single answer that will solve all of our future problems. There’s no magic bullet. Instead there are thousands of answers – at least. You can be one of them if you choose to be.”