"IMMIGRANTS -- WE GET THE JOB DONE!"

A question haunts our history. Who built America?

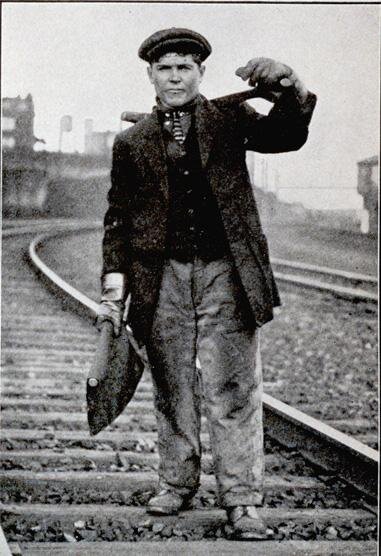

Who built the skyscrapers? Who dug the mines? Who forged steel into bridges? Who wove our fabrics and sowed our clothes? The question has a broad answer — immigrants. Poles, Italians, Germans, Swedes, Slovaks, Greeks, and more. Arriving from throughout Europe, they built this country for bottom dollar wages.

But one monumental labor has a different answer. Who built the railroad that spanned the continent? Scanning the faces in the famous picture above, you might fall back on Europeans. You might even, like Nixon’s Secretary of Transportation, opt for “Americans.” Because “who else but Americans could have laid ten miles of track in twelve hours?” But John Volpe was wrong. America’s Transcontinental Railroad — “nothing like it in the world” — has a Chinese flavor, with an Irish brogue.

In January 1863, in a field outside Sacramento, railroad tycoon Leland Stanford dug the first shovel of earth. The Central Pacific was eastbound. Ten months later, the Union Pacific broke ground in Omaha. The race was on.

But with the Civil War raging, American labor busy. Needing thousands of hired hands, Stanford’s fellow Robber Baron Charles Crocker asked — why not the Chinese?

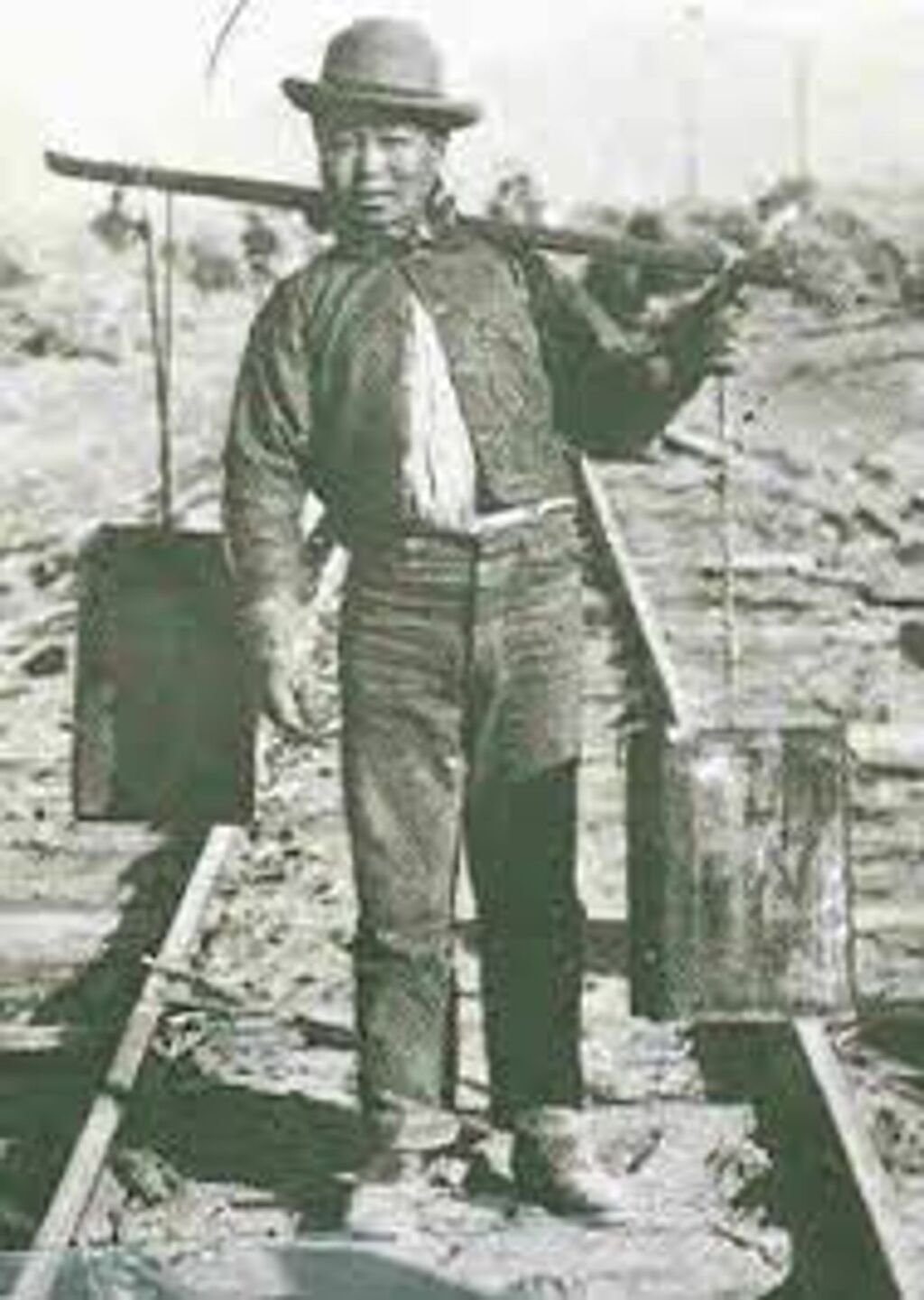

Some 50,000 Chinese, nicknamed “Celestials,” came to California in search of gold. When America’s “Gold Mountain” proved elusive, they stayed on as small merchants. Some worked on railroads linking California, but the Leland Stanford had doubts. The Chinese, he said, were “an inferior race.” Charles Crocker answered: "Did they not build the Chinese Wall, the biggest piece of masonry in the world?"

Early in 1864, fifty Chinese began clearing Dutch Flat outside Sacramento. Then another fifty came. And another. And. . .

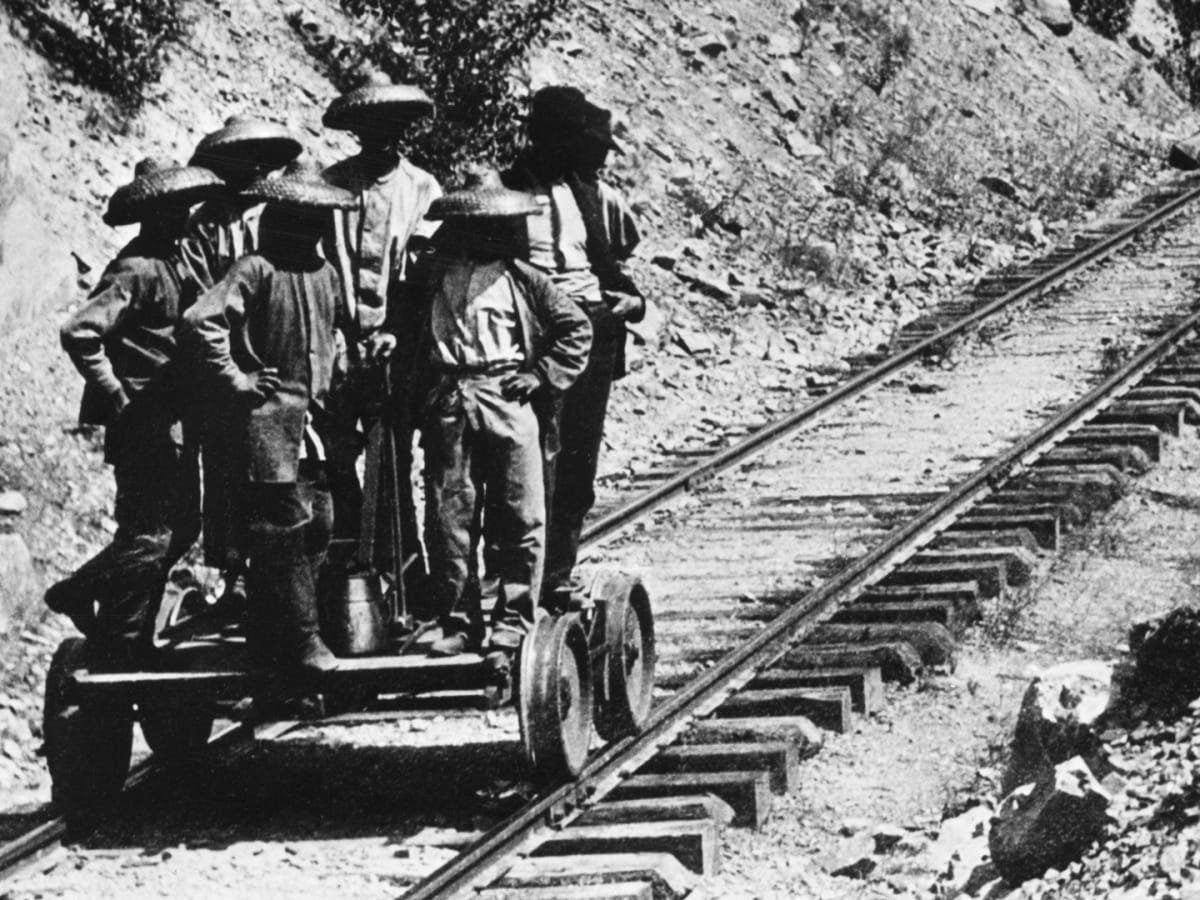

Soon the impossible work began — building a railroad across the Sierras. By the end of 1865, some 8,000 Chinese were opening tunnels a quarter mile long. Their tools? Dynamite, nitro-glycerine, picks and shovels. Joined by shiploads of men recruited back in Canton province, the Chinese labored 12-hour days, six days a week. Their pay — $26 a month — half what non-Chinese made.

Meanwhile out on the Plains, the Union Pacific had its own immigrants — the Irish. Ten thousand cleared the land, dodged native-Americans, and laid track westward. Eating boiled meat and potatoes, drinking local water or whiskey, many Irish took sick. The Chinese, providing their own food, dined on rice and vegetables, drank only tea, and worked on. Foremen marveled. Even Leland Stanford was impressed, calling the Chinese “quiet, peaceable, patient, industrious, and economical.”

The names of the places they linked were colorful and Californian. Grizzly Hill. Eminent Gap. Horse Ravine. Truckee. But the names of the laborers are lost to history. Payroll records record Irish surnames — O’Connell and McBride — but few foremen could pronounce Chinese names. Paychecks were issued en masse to “John Chinaman.”

As John Chinaman’s railroad soared, stories spread of men tunneling through solid rock. Men dangling from ropes flung over steep slopes, men inserting dynamite in crags, then scrambling for safety. The Chines survived snow piled to 40 feet. They dug through ice and lived for weeks in frozen caves. Hundreds, perhaps a thousand, died. Their bones were collected and shipped home to China. The rest toiled on.

But their patience had a limit. In June 1867, after a landslide buried 20 workers, the Chinese lay down their shovels and folded their arms. Their strike lasted eight days, winning concessions for safety, but no higher pay.

By 1868, the Central Pacific was laying track on the Nevada desert. Each locomotive pulling supplies to track’s end had a separate car, the China Store, selling food, tea, and ginseng. The one day in 1868, Central Pacific laborers laid ten miles of track in a single day. Americans? The few hundred Irish, perhaps, but all Chinese were barred from American citizenship until 1943.

Finally, the tracks met. Leland Stanford drove the golden spike. Wired to a telegraph, it sent a message to the White House. “DONE!” But when the famous photo was taken, the Chinese were erased from history, herded off the track, out of the frame. The erasure lasted for a century, the century of the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, the century of anti-Chinese riots, the century of silly stereotypes and Charlie Chan.

At the 1969 railroad centennial, the lone speaker from the Chinese Historical Society was canceled at the last minute. It took decades for the full story to emerge.

In 2013, at the university endowed by Leland Stanford, the Chinese Railroad Workers of North America Project began digging in newspaper archives, talking to descendants, unearthing the truth. Six years later, at the 150th anniversary, project director Gordon Chang welcomed hundreds of Chinese. Among them was Secretary of Transportation Elaine Chao.

The Chinese work on the Transcontinental Railroad, Chao said, was “every bit as consequential as the digital revolution that binds the world today.”

So who built America? The answer lies down a long and winding track.