WINIFRED REMBERT -- LEATHER SOUL

Leather is a soulful material. Once a living hide, it comes back to life in the hands of skilled craftsmen. Strong yet supple, it bends in a child’s hands but the strongest adult can’t tear it. Leather seems enduring, yet in belts and billfolds, shoes and purses, it finally fades, cracks, surrenders. Unless the leather is fashioned into a life.

“When an old man dies,” an African saying has it, “it is as if a library burned.” But when Winfred Rembert died last March, the library of his remarkable life lived on. Because this humble, tortured, resurgent man hammered his story into leather, letting the world know that not even the chain gang, the near lynching, the sorrows of Jim Crow could keep him down.

Rembert, one obit noted, was “an irrepressible man of many talents who was impossible not to love,” but that was not how rural Georgia saw him.

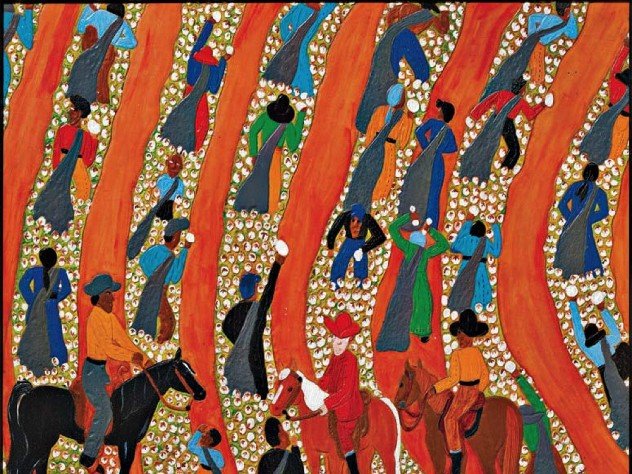

Born a dozen miles from the Alabama line, Rembert began picking cotton at age six, earning his family a dollar a day. “Curved cotton rows make a beautiful pattern,” he recalled, “but as soon as you start picking, you forget how good it looks.”

Missing class for harvests, Rembert did not learn to read until high school, but he soon left school to hang out at juke joints. Feet’s Pool Hall. Bubba Duke. The Dirty Spoon Cafe.

Then came Civil Rights.

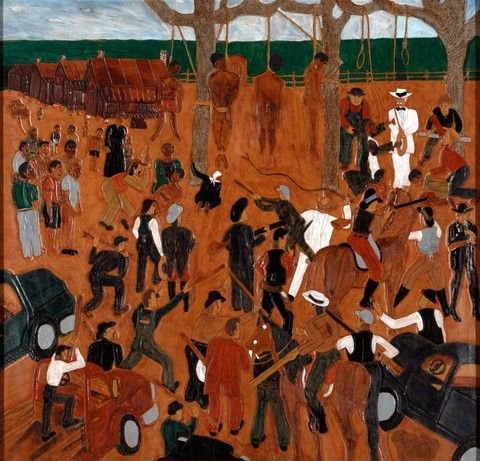

In April 1965, Rembert’s life was derailed when a march in nearby Americus turned violent. When men with shotguns chased him down an alley, he spotted a parked car with keys. He fled but was caught and jailed for auto theft. A year later, he escaped but was caught again. This time, his pursuers “weren’t playin’.”

“I saw all of these white people, and I see these ropes hanging in the tree. They took off all of my clothes, put the noose around my ankles, and they drew me up in this tree. The next thing I see was the deputy sheriff. . . He took his knife, grabbed my private parts, and he stuck me with the blade. You could probably hear me for miles screaming.”

Rembert’s life was saved by a white man who called off the lynch mob. For seven years, Rembert toiled on a chain gang, somehow surviving “the cruelty you go through for being black.”

Released in 1974, Rembert and his new bride fled north and tried to forget, but he had nightmares “almost every night. Lots of times I’d get up out of the bed with Patsy and go in the bathroom and just sit there and cry.”

While in prison, he had learned to work with leather, shaping, imprinting, dyeing. For two decades, work and raising eight children in New Haven kept Rembert busy, but in the mid-1990s, when he found time for leather, his stories were waiting. His first work soon hung in a friend’s bookstore. When a customer offered $300, Rembert was shocked. His wife was not. Her husband was so full of life, so why not. . .

“We can put them stories on the leather.”

“I said, ‘Get out of here, Patsy, no one wants that.’”

Juke joints. Cotton fields. Dancing, singing, surviving. Even if no one wanted such stories, the stories wanted to be told. Rembert soon found himself working with leather, working on into the night. Watch:

A second work sold for $750. When friends helped Rembert buy tools, he began shaping his life into leather. In 1998, a one-man show at a New Haven theater led to a Yale Art Gallery exhibit, then shows in Harlem, Atlanta, L.A. The stories kept coming. “I’ll be a dead person before I put all this stuff down,” he said.

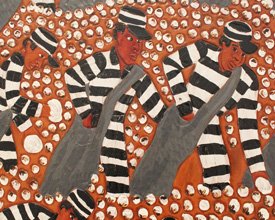

Despite striking colors and sinuous shapes, some of Rembert’s images are hard to look at. Here is Rembert fleeing his pursuers. Here is slavery. Here is the chain gang, “all about work and bustin’ you down.” He spared no viewer, hid no memory.

“With my paintings, I tried to make a bad situation look good. You can’t make the chain gang look good in any way besides by putting it in art. Those black and white stripes look good on canvas. People can’t really tell what they are until they get up close.”

In 2010, the former cotton picker, survivor of a lynching, had a one-man show on Manhattan’s Upper West Side. Rembert found himself compared to Jacob Lawrence and Faith Ringgold. At prices well into five figures, the show sold out. Soon Rembert was telling his stories in documentaries, to school groups, on NPR. His Georgia hometown held Winfred Rembert Day. Jimmy Carter showed up, but Rembert was more amazed by breakfast in his boyhood home.

“It was breakfast for a king,” he recalled. “To have a white woman cooking breakfast for a black man. . .”

On into his 70s, Rembert earned commissions, fellowships, and growing acclaim. And when, in his final year, he finished Chasing Me to My Grave, the story was done, told, released. But although his memoir was hailed as “a stunning portrait of hope,” words are less durable than leather.

“Leather takes a beating,” Rembert wrote, “and whatever you do with it, it will hold its shape. You can carve it up and it will hold your picture.”