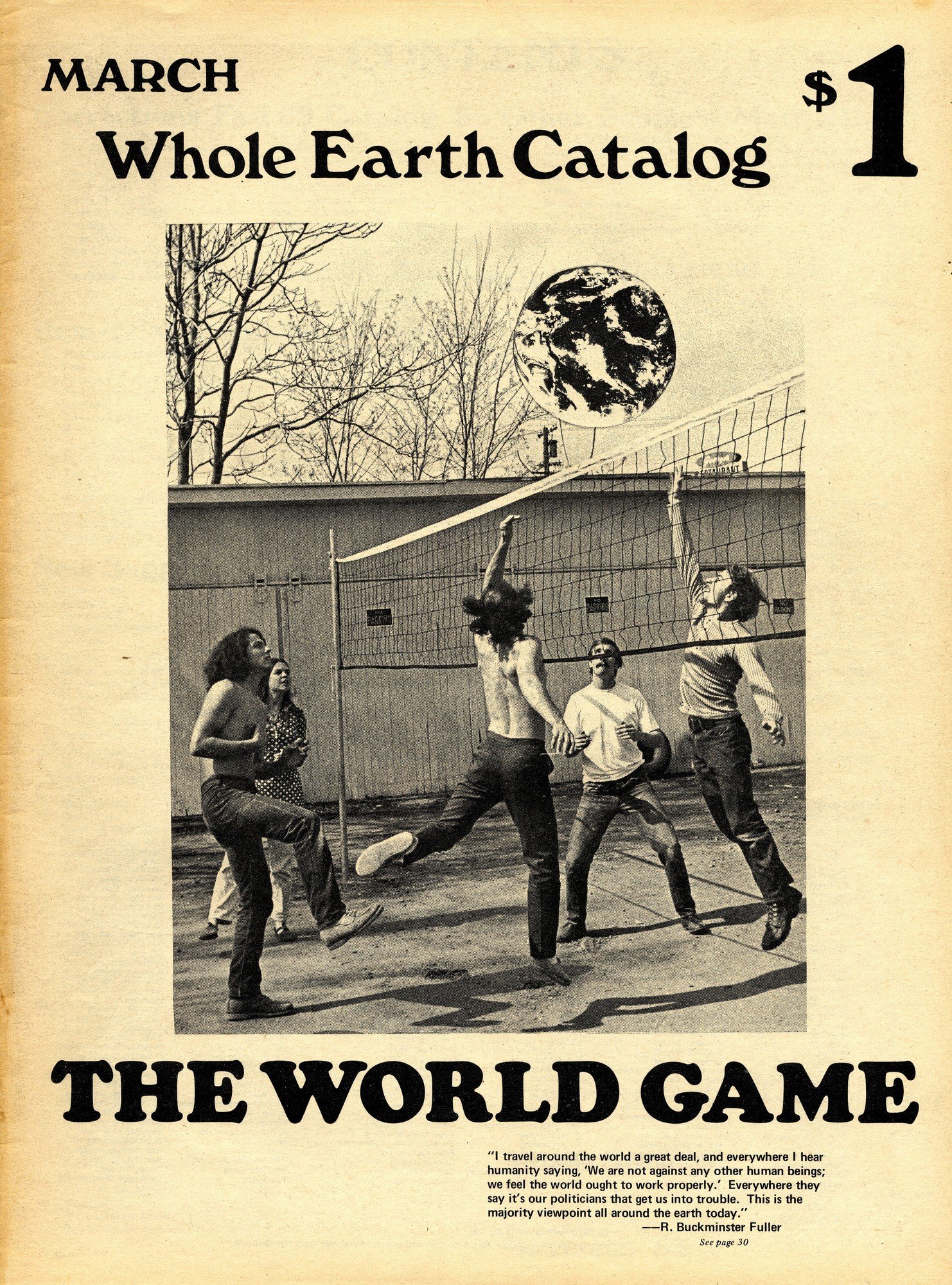

THE WHOLE EARTH'S QUIRKY CATALOG

A link connects the screen you’re reading with the catalog in question. Call it a long, strange trip.

One foggy summer afternoon, Stewart Brand stepped onto his rooftop in San Francisco. The mist and skyline were magical but not enough. By natural insight, or with the help of LSD, Brand saw himself soaring above the earth. He saw curvature, clouds, oceans. Soon he saw the whole earth, a blue marble suspended in space. Satellites had photographed the planet, but “there we were in 1966, having seen a lot of the moon and a lot of hunks of the earth, but never the complete mandala."

Brand started a campaign — buttons and letters to scientists, politicians, NASA. When he got no response, he doubled down on the whole earth. He started with a catalog.

The Whole Earth Catalog lasted just three years. Updated versions followed, but the Whole Earth community moved on to new horizons, mostly digital. So what was this catalog and why do so many say it changed their lives?

Though seen as a “counterculture bible,” the Whole Earth Catalog listed few products related to sex, drugs, or rock n’roll. Instead, it offered tools. On page 3, Brand explained:

“We are as gods and might as well get good at it. . . A realm of intimate, personal power is developing — power of the individual to conduct his own education, find his own inspiration, shape his own environment, and share his adventure with whoever is interested. Tools that aid this process are sought and promoted by the WHOLE EARTH CATALOG.”

The catalog mirrored the mind of its creator. And with all due respect to catalog pioneers Mr. Sears and Mr. Roebuck, few minds are as expansive as Stewart Brand’s.

Brand headed west from Illinois in 1958 to study biology at Stanford. But in (legal) lab experiments with LSD, he found altered states. In 1964, he joined Ken Kesey’s Merry Prankster’s, riding the psychedelic bus labeled “Further.” He soon organized the first Trips Festival, then stepped onto a rooftop. Human thought was changing, evolving. People needed tools.

In 1967, Brand converted a ‘63 Dodge pickup into the Whole Earth Truck Store. Roaming the Southwest, he visited communes and sold farm tools and books about simple living. Noting how communards enjoyed the store’s catalog, Brand came home, set up a storefront, and hired an art student as designer.

The first Whole Earth Catalog emerged in 1968. By then, NASA had released a whole earth photo, and there it was on the cover. The marble. The spaceship. Between covers, on pages seemingly cut and pasted, Whole Earthers found:

Garden tools, carpenters' tools, potters wheels. Tents and hiking shoes. Magazines, auto repair manuals, organic gardening guides. But just when the catalog seemed Sears and Roebuck gone green, the mind of Stewart Brand booted up.

The Whole Earth Catalog introduced a generation to designer Buckminster Fuller, whose geodesic domes soon graced several communes. The catalog sold an early desktop calculator and books on video production. You could read about kibbutzes, self-hypnosis, or an esoteric eastern practice called Yoga. And on page 34 was a handbook on cybernetics, the M.I.T. based system that was changing computer science.

“When I was young,” Steve Jobs recalled, “there was an amazing publication called The Whole Earth Catalog, which was one of the bibles of my generation. It was sort of like Google in paperback form, 35 years before Google came along. It was idealistic and overflowing with neat tools and great notions.”

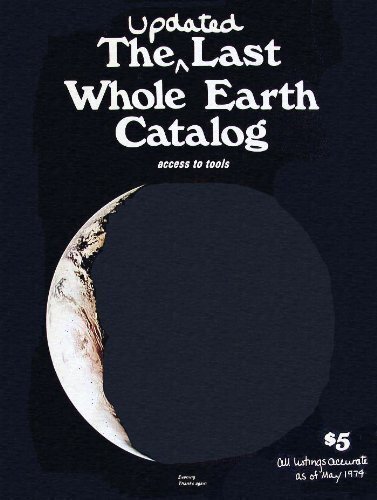

New catalogs followed, with new tools, ideas, and images of the whole earth. Back covers offered Zenlike wisdom. The earth as a crescent — “Evening again. Good night.” The earth rising: “We can’t put it together. It is together.”

The debut catalog ran 63 pages. The last catalog, 452 pages, won a National Book Award. But Brand measured success not by sales but by influence. Foreseeing the end just 20 months ahead, he wrote: “If by that time there aren’t people and ideas around doing a better job than us, then we will have failed. We won’t have replaced ourselves. Most likely, though, we’ll be obsolescent and in the way, and our departure will be occasion for sighs and relief and a party.”

The Demise Party came in June 1971, by invitation only. Dress? “You could come as a tool.” At party’s end, Brand gave $20,000 in profits to guests as seed money. And seeds were sown.

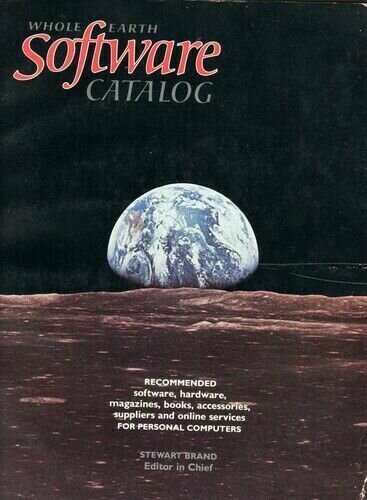

The Whole Earth Catalog spawned versions in several countries. And The New Woman’s Survival Catalog. And a magazine — Co-Evolution Quarterly. And occasional updates. But Stewart Brand went Further.

In 1992, when personal computers seemed risen from garages and nerdfests, Brand wrote, “Blame it on the hippies.” It was the counter-culture, the Bay Area dream of “intimate, personal power” that led Steve Jobs and others take Brand’s advice — “We are as gods. . .”

Today, Stewart Brand runs the Long Now Foundation, created to foster long-term thinking. Images of the Whole Earth are on flags, calendars, tote bags. . . And the catalog’s farewell, from the 1974 Whole Earth Epilog, remains a mantra for the forever young.