WALKING AMERICA WITH THE MASTER

CONCORD, MA — 1842 — Folks in this small town near Boston knew the young slacker Thoreau, all right. Never did a lick of work. Set fire to the woods while cooking chowder. Left teaching because he couldn’t bear to whip students with the customary cane. And what did this good-for-nothing product of Harvard do all day? He walked.

“I think that I cannot preserve my health and spirits, unless I spend four hours a day at least—and it is commonly more than that—sauntering through the woods and over the hills and fields, absolutely free from all worldly engagements.”

One July morning, a week after his 25th birthday, Thoreau could stand it no longer. Having “traveled a good deal in Concord” he heard the call of the Wild, the West. “Eastward I go only by force, but westward I go free.”

No railroad yet went west from Concord. Thoreau had no horse. So he and a friend set out on foot. All day they passed cabins, pastures, and meadows. Stopping by streams, they read Virgil. They stayed at an inn and by noon the next day they stood atop Mount Wachusett, 34 miles from home.

“Our eyes rested on no painted ceiling nor carpeted hall, but on skies of nature's painting, and hills and forests of her embroidery. . . It was a place where gods might wander.”

The next day they hiked home. American walking had found its Rembrandt.

“I have met with but one or two persons in the course of my life who understood the art of Walking, that is, of taking walks -- who had a genius, so to speak, for sauntering.”

Sauntering through a short but sublime life, Henry David Thoreau gave America a master class in the art. He soon learned that “two or three hours' walking will carry me to as strange a country as I expect ever to see.” In an emerging nation, he saw a role for the walker. “The chivalric and heroic spirit which once belonged to the chevalier or rider only, now seems to reside in the walker.”

Two summers after his overnight hike, Thoreau set out again — alone. His knapsack held a few books, a tin cup, and a change of clothes. Picking raspberries, buying bread at farmhouses, he hiked the breadth of Massachusetts, crossing the Connecticut River, climbing the Berkshires, arriving finally at the foot of Mount Greylock. After buying rice and sugar, he started up.

Farmers thought him a local college student, but students took the beaten path. Thoreau, knowing that “all good things go wild and free,” found his own route.

The summit lay five hours ahead, a farmer told him. Unless he went up the side, but there was no path, “and I should find it as steep as the roof of a house. But I knew that I was more used to woods and mountains than he.” So Thoreau crossed a cow pasture and began bushwhacking. Two hours later, he stood at 3,600 feet.

“All around beneath me was spread for a hundred miles on every side, as far as the eye could reach, an undulating country of clouds, answering in the varied swell of its surface to the terrestrial world it veiled. It was such a country as we might see in dreams, with all the delights of paradise.”

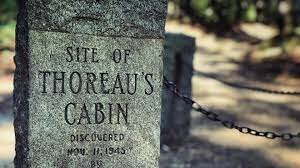

The following summer, Thoreau moved into a cabin on Walden Pond. He did not go there to walk. “I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived.”

Yet Thoreau’s experiment in simple living included daily walks — around the pond, back into town, into the night. . . When it was over, he went back to Concord, but later walked to Cape Cod four times, to Maine’s Mount Katahdin, wherever his wanderlust led.

We know about all this because Thoreau turned adventure into stories. First in journals, then in lectures, finally in essays, Thoreau taught America to revere the walker. The lone saunterer is not some lazy vagabond, nor an escape artist. The walker follows a call — to explore, to take chances, to “live deliberately.”

Thoreau died before his legs gave out, succumbing to TB at forty-four. A month later, his essay “Walking” appeared in The Atlantic. This and other writing linked him to the American Renaissance that included Whitman, Melville, and Emily Dickinson. But those writers wrote from home. A century before Kerouac, Thoreau put American lit “on the road.”

“For every walk is a sort of crusade, preached by some Peter the Hermit in us, to go forth and reconquer this Holy Land from the hands of the Infidels. . . If you are ready to leave father and mother, and brother and sister, and wife and child and friends, and never see them again--if you have paid your debts, and made your will, and settled all your affairs, and are a free man--then you are ready for a walk.“