THE ART OF REBUILDING A NEIGHBORHOOD

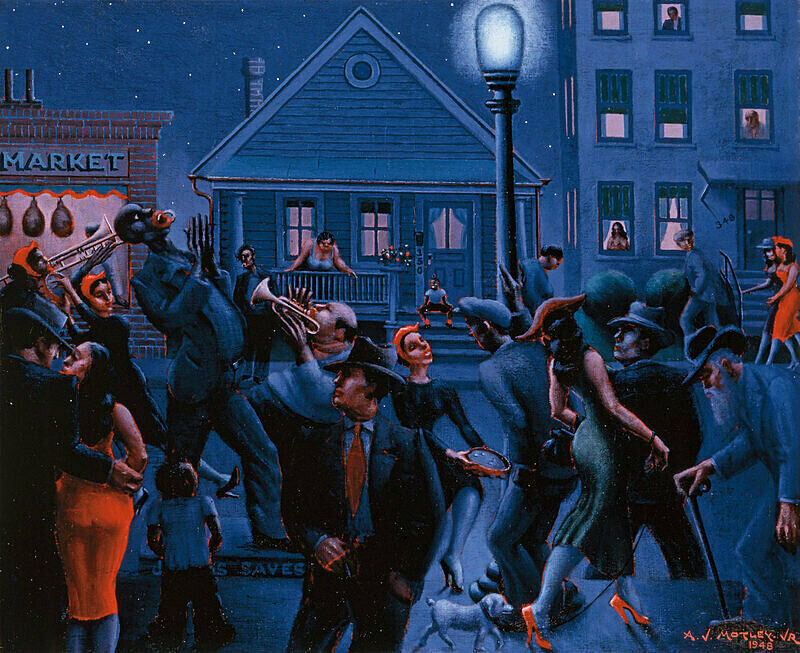

SOUTH CHICAGO — Like Harlem before it, Chicago had its Black Renaissance. During decades of Depression and war, the neighborhood folks called Bronzeville blossomed with art, literature, and music. Louis Armstrong was blowing his horn. Richard Wright was writing Black Boy and Native Son. Community art centers welcomed young talent. Poetry and prose boosted pride.

And then came the era “when work disappeared.” After a grudging integration opened schools and other opportunities, the tight-knit all-black communities fragmented. Population plummeted. Jobs dried up. Buildings were abandoned. You know this story. It’s one story of America. But who said the term “renaissance” is always about history?

In 2007, Theaster Gates was hired to coordinate community arts programs for the University of Chicago. Between his own art, shown at major museums, and his job at the prestigious university, Gates could have lived elsewhere in Chicago but he chose “the place people leave or are stuck in,” a neglected South Chicago neighborhood called Grand Crossing. There he bought an abandoned candy store and moved in, then bought the house next door — for $18,000 — and began dreaming.

Gates grew up in Chicago, on the West Side, the son of a roofer and a school teacher, with eight older sisters. The gospel of his church choir introduced him to aesthetics, but he did not discover art until college. There he began collecting the ambient materials of poverty — bricks, broken boards, and other detritus — and turning it into art. When he took dozens of fire hoses, like those turned on Civil Rights protestors, and made “Minority/Majority,” museums began taking notice.

Art soon took Gates to Japan and South Africa where he focused on pottery. And pottery taught him “to make great things out of nothing. As a potter, you also learn how to shape the world.”

So when he came home to Chicago, Gates began shaping his world. Some call this “urban renewal.” Gates calls it “curating” a neighborhood.

Working with architects, planners, and builders, Gates turned the house next door into The Archive House, a cultural hub that soon hosted lectures, exhibits, poetry readings, and more.

Next came The Listening House, an abandoned home resuscitated into a library of music and poetry. Three more abandoned buildings became arts centers. A former crack house became the Black Cinema House whose screenings drew sellout crowds.

In 2010, Gates formed the non-profit Rebuild Foundation. Today Rebuild owns 80 buildings in South Chicago. Its projects include:

— a former elementary school being converted into an arts incubator;

— a former power plant soon to be a woodworking studio;

— a greenspace, Kenwood Gardens, now sprouting with small artists studios;

— and a bank.

In 2013, Rebuild bought the Stony Island Trust and Savings Bank, 17,000 square feet of urban blight. The cost: $1. The bank, abandoned for years, had six feet of standing water beneath rotting ceilings and mildewed walls. “We just started imagining,” Gates recalled. “What else could happen in this building?”

First, Rebuild stripped out the bank’s marble and chopped it into pieces. These “bank bonds” sold for $5,000 each, jumpstarting the massive project. The work went on for years until, today, the bank houses a library, an archive of the magazines Ebony and Jet, and a collection of memorabilia from the black community. The bank, like all Rebuild projects, reflects the foundation’s core values: “black people matter, black spaces matter, and black objects matter.”

While curating, Gates has continued his own art. Now a full professor at the U. of Chicago, he has shown in museums throughout the U.S. and Europe. Gates’ renaissance work has won him many awards, including the Wall Street Journal’s “Innovator of the Year,” yet he does not see rebuilding as heroic. He thinks of it as radical.

In neighborhoods where everyone else has left, he says, “where there is abject poverty, simply choosing to stay becomes a radical act.” And while staying on in Grand Crossing, Gates is now consulting with Renaissance men and women in other cities.

“Where neighborhoods have failed,” he says, “they still often have a pulse. Detroit, Akron, Ohio, Gary, Indiana — there are people in those places who already believe in those places. They’re already dying to make those places beautiful. So now we’re starting to give advice around the country on how to start with what you got.”

For better and worse, it’s one American story: segregation and racism exclude a people but their spirit flourishes in defiance. Opportunity knocks, sort of, and many move on, move out. Then, as if some inner cities should be called Phoenix, the spirt rises again from its own ashes. But having seen his “curating” grow “from a bowl to a single house to a block to a neighborhood to a cultural district,” Theaster Gates knows there is still much work to do.

“The truth of the project is that so much more is needed from us all, policy makers, writers, activists, lobbyists, businessmen and women, preachers and teachers and thinkers and artists.” Think of the future, then, as clay on a wheel.