LITTLE MISS SURE SHOT -- ANNIE OAKLEY

“When Americans tell stories about themselves,” historian Richard White noted, “they set them in the West.”

So we have stories of leathery cowboys, brave sheriffs, proud and defiant natives. But one story of the West wears a skirt, speaks like “a lady,” and can shoot the ashes off a cigar at 30 paces.

According to the story, on Thanksgiving Day in 1875 — or perhaps 1881 — the traveling show of Baugham and Butler came to town. The town was Cincinnati and the show was a shootin’ match. Irish immigrant Frank Butler shot holes in everything that didn’t move, then issued a challenge — with a $100 stake — to any local marks-man. And up stepped a girl, just five feet tall and 15 years old — or perhaps 21.

“I was a beaten man the moment she appeared," Butler said, "for I was taken off guard.” Butler and his challenger each set up 25 targets. Bang! Boom! Each hit the first two dozen. Then Butler missed his last shot. The girl hit hers and a legend was born. Because, as the song says, “There’s no business like show business.”

Behind the legend of Annie Oakley are some harsh facts. Born on the Ohio frontier, Phoebe Ann Mosley grew up in dire poverty. The sixth of nine children, she was “bound out” to a nearby family after her father died. Toiling for a couple she later called “the wolves,” Mosley was enslaved, abused, abandoned. But when she took up hunting — at age eight — she did “what comes naturally.”

“I saw a squirrel run down over the grass in front of the house, through the orchard and stop on a fence,” she recalled. Grabbing a rifle, Phoebe fired. "It was a wonderful shot, going right through the head from side to side."

After fleeing “the wolves” and returning to her family, Phoebe took up hunting. Bringing in food and selling the surplus, she paid off the family farm. Word spread, making her famous throughout Western Ohio. A Cincinnati hotel manager set her up to challenge Frank Butler, and when she beat him, she won more than a bet. Frank Butler and Phoebe Mosely were soon married and on tour. He did the shooting, while she managed affairs, until. . .

One day in 1882, Butler’s shooting pardner took sick. Butler got his wife into the act but when he kept missing, so the story goes, someone shouted, "Let the girl shoot!" Mrs. Butler stepped up, blew away every target, and within a year, she was the star. She took the last name Oakley, after the Cincinnati neighborhood where the couple lived.

By 1885, Annie Oakley was touring in Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show. The show was pure mythology, glorifying guns and putting native Americans on shameless display. But its biggest star was not the self-promoting Buffalo Bill but Annie Oakley.

While others strutted, all duded up, Annie appeared in a modest dress she had sewn herself. She did not twirl pistols, never fired in the air. She merely set up targets and took aim. A playing card at 30 paces. Bam! Split in half. A cigar in her husband’s mouth. Boom, ashes gone. A candle across the stage. Poof! Snuffed out.

Audiences loved Annie. Buffalo Bill loved the box office. And another troupe member, Sitting Bull, took a shine to Annie, calling her “Little Miss Sure Shot.”

The rest, of course, is more legend. How the show toured Europe, with the Ohio sureshot meeting royalty, picking off targets in Paris, shooting a cigar from the hand of Kaiser Wilhelm. The name Annie Oakley became synonymous with precision and poise. Complimentary theater tickets, punched with a hole, were called “Annie Oakleys.” Annie joined other Western legends — from Billy the Kid to Wyatt Earp — as the star of dime novels. And when Thomas Edison needed subjects for his pioneering movies, Buffalo Bill volunteered Annie. . .

Annie toured until a train accident in 1901 left her paralyzed. She recovered after several surgeries. Then, as often happens to legends, she was targeted in the press. A story in the Hearst papers said she’d been arrested for stealing to support a cocaine habit. Never one to back down, Annie sued and hit the mark, winning 54 of 55 libel suits.

Moving in and out of retirement, Annie kept shooting. She and Frank gave much of their earnings to orphanages. Believing women should hand guns “as well as they handle babies,” Annie taught some 2,000 women to shoot.

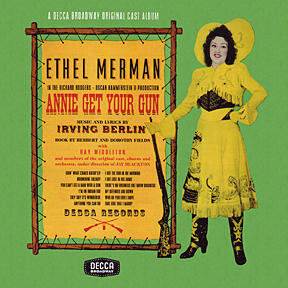

After Annie died in 1926, Western legends faded. Then shortly after World War II, she hit Broadway in the musical “Annie Get Your Gun.” Its made-for-stage story, plus such Irving Berlin songs as “There’s No Business Like Show Business” and “Doin’ What Comes Naturally,” made it an instant hit, revived again and again. Then came a TV western, biographies, and the National Women’s Hall of Fame.

The Western legend that wore a dress remains a household word. Her parting shot is a piece of advice: “Aim for the high mark and you will hit it. No, not the first time, not the second time and maybe not the third. But keep on aiming and keep on shooting for only practice will make you perfect. Finally you'll hit the bull's-eye of success.”