THE MOTHER, THE DAUGHTER, THE "LITTLE HOUSE"

THE PRAIRIE, THE DEPRESSION — Hot winds blow across the plains as the writer opens a letter from a New York publisher. An editor at Knopf is raving about When Grandma Was Young. “I have read it with the greatest interest. I like the material you have used. It covers a period in American history about which very little has been written, and almost nothing for boys and girls.”

The writer is confused. Though she has described her prairie childhood in newspapers, publishers have rejected her memoir, Pioneer Girl, again and again. At 53, her writing is going nowhere. So what’s this about grandma? And writing “for boys and girls?”

The world knows Laura Ingalls Wilder for her “Little House” books which have sold 60 million copies. But the world is only beginning to learn about Laura’s daughter, Rose. And the story of how mother and daughter worked together — writing, re-writing, sharing stories — is, like the “Little House” books themselves, enduringly American.

Laura Ingalls’ childhood was not so homespun as her stories. Born in the Wisconsin woods in 1867, she followed “Pa and Ma” throughout the Midwest as they struggled to live off the land. A brother died in infancy. Fire burned down the barn. Drought scorched the fields. And in covered wagons, the Ingalls rode from Wisconsin to Kansas, on to Minnesota, Iowa, finally South Dakota. Living in log cabins, surviving icebound winters, locusts, despair, the family kept its spirits up. “We had no choice. Sadness was as dangerous as panthers and bears. The wilderness needs your whole attention.”

Laura married at 18 and soon gave birth to Rose. A second child survived only ten days, leaving Laura and Rose alone in the mother-daughter minefield. Like Laura, Rose was bright, articulate, strong-willed. The girl could barely wait to get out of South Dakota, and at 15 she was sent to Louisiana to live with an aunt.

But a year later, Rose was back home, learning Morse code to become a telegrapher. After dull years working for railroads, she followed a man to San Francisco where she began writing for newspapers, then magazines.

By 1920, Rose Wilder Lane was a successful freelancer. Divorced, independent, Rose wrote for national magazines, reporting from Europe and America. Meanwhile, Laura stayed home on the prairie, occasionally writing for local papers but mostly helping her husband tend the farm.

In 1928, Rose, suffering from bi-polar disorder, came home to Missouri and built a house next to her parents’ farmstead. Then came the crash.

When the stock market tanked, Rose and Laura lost their life savings. Reeling from the loss and the deaths of her mother and sister, Laura began a memoir. In the summer of 1930, she handed Rose 200 pages scribbled on tablets. Rose got to work.

The Depression left even the celebrated Rose Wilder Lane searching for money and markets. When her publishing contacts rejected Pioneer Girl, Rose was desperate. Moving to Connecticut, she took Laura’s manuscript and told no one. Removing horrific memories — of fires, diphtheria, death — and pumping up the homespun fortitude, she crafted When Grandma Was Young.

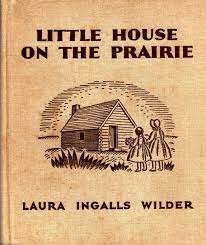

When Laura heard from Knopf, Rose revealed her plan, then encouraged her mother to expand the novella with “any and all details about the way of living, what you played, what you ate, wore, everything like that,” Laura renamed the book Little House in the Big Woods. Reading the manuscript on a commuter train, an editor missed her stop. “The real magic was in the telling. One felt that one was listening, not reading. All of us were hoping for that miracle book that no Depression could stop.”

The first Little House book came out in 1932. Laura got a $500 royalty check, the smallest she would ever receive, and began writing about her husband’s childhood. Rose came home to help and for the next few years, mother and daughter were the most successful writing team in America. When Laura finished Farmer Boy, Rose edited it — lightly.

“The changes I made, as you will see, are so slight that they could not even properly be called editing. It is really your own work, practically word for word.”

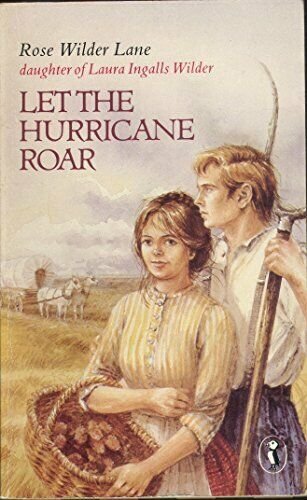

Meanwhile, Rose wrote her own novels, basing them on Laura’s parents’ prairie life, hardship included. Let the Hurricane Roar and Free Land tapped Depression era hunger for stories of grit and survival. “Perhaps,” the New York Times observed, “Mrs. Lane wants us to take a lesson in courage from the early settlers.”

But the strong-willed writers soon clashed. Craving more time for her own writing, Rose returned to Connecticut, but the collaboration continued through the “Little House” series, the last book coming out in 1943. By then, Rose was consumed with the stories — some say the “myth” — she had midwifed. She spent her final decades denouncing all government programs and promoting libertarian politics.

Laura died in 1957, at 90. Rose kept writing, even reporting from Vietnam at age 78. When she died in 1968, she was buried on the prairie, beside her parents.

“It sounds, to tell it,” Rose wrote, “as if they’d known nothing but calamities but the truth is they didn’t expect much in this world and they just shed thankfulness around them for what they had.”