THE ADS THAT TICKLED THE WASTELAND

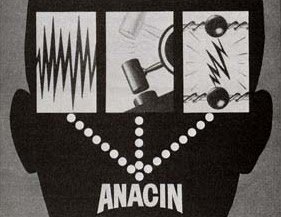

THE VAST WASTELAND — 1960s — During the dumbest days of television, commercials were as stupid as the shows. Mr. Clean and Listerine and Josephine the Plumber. There was a giant in your washer, a white knight riding to rescue your laundry. So imagine, you Mad Men, your newest client.

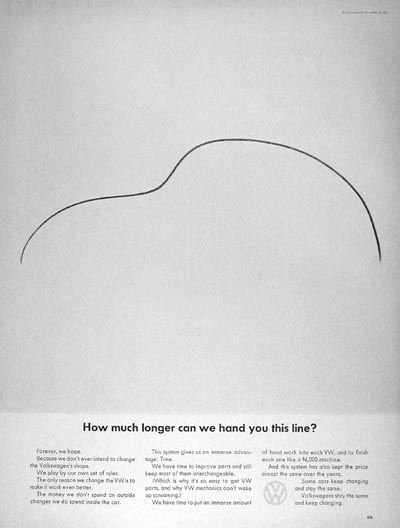

It’s a car but not some high-fin chrome coupe. This car is small, wimpy, kind of ugly. No red-blooded American, raised on Cadillacs and Chevys, could possibly want one. Oh, and this car? It was designed by Nazis. So what’s your pitch?

“Think Small” was more than just an ad. This singular campaign, one historian noted, “changed the culture of advertising.” Before “Think Small,” Madison Avenue’s holy grail was the USP, the unique selling point. Using market research and statistics, ad men pitched their products as New, Improved, Life-changing!

Slogans were drummed into brain-washed minds. “Melts in your mouth. . . “ “You’ll wonder where the yellow went. . .” “See the USA in your Chevrolet. . .” But one ad man, though he looked as buttoned-down as the rest, saw that “rules are what the artist breaks; the memorable never emerged from a formula.”

From a single ad he wrote while working the mail room of a liquor company, Bill Bernbach rose to creative director of a major agency. Then in 1949, he started his own firm. Years of drudgery on Madison Avenue taught Bernbach a life-changing lesson.

“There are a lot of great technicians in advertising, and unfortunately they talk the best game,” Bernbach said. “They are the scientists of advertising. But there's one little rub. Advertising is fundamentally persuasion, and persuasion happens to be not a science but an art.”

Doyle, Dane, Bernbach, known in the trade as DDB, broke all the rules. Copywriters and artists, instead of working on separate floors, worked as a team. Research, which “leads to conformity,” was replaced by imagination. If a client didn’t like a campaign, too bad. It would run anyway. And instead of being drudges in grey flannel, ad men became “creative geniuses.”

“We just felt very free,” one DDB genius remembered, “as if we had broken our shackles, had gotten out of jail.”

The results reached every TV and magazine in America. Avis Rent-a-car, whose execs hated their new slogan — “We’re number two” — went from huge losses to huge profits. American Tourister saw their suitcases battered by gorillas to show their strength. Burlington socks saw a businessman in boxers doing a joyful dance while his socks stayed firmly in place. And all those slick pitchmen, were replaced by folks who talked like you and me. Even like kids.

“Mikey likes it!”

Bill Bernbach had made good on his promise. “All of us who professionally use the mass media are the shapers of society,” he said. “We can vulgarize that society. We can brutalize it. Or we can help lift it onto a higher level."

Breaking every rule, DDB tapped the disruptive Zeitgeist of the Sixties. Ad-sated consumers still wanted to consume but they wanted their products to be different, even — dare we say it — cool. So DDB ads were the first to admit they were ads. “Don’t bother to read this ad,” one Chivas Regal pitch proclaimed. Calvert Whiskey openly asked whether “the soft whiskey,” was “just another slogan.”

In The Conquest of Cool, Thomas Frank explained Bernbach’s impact on advertising. “The ads his agency produced had an uncanny ability to cut through the overblown advertising rhetoric of the 1950s, to speak to readers’ and viewers’ skepticism of advertising, to replace obvious puffery with what appeared to be straight talk.” Watch.

On through the decade, DDB was “the unchallenged leader of the creative revolution of the Sixties.” But success spawned imitators. Other agencies began breaking rules, inspiring Benson and Hedges to mock their cigarette’s length, leading Alka-Seltzer to drop its “Speedy” mascot in favor of pitches that became cultural talking points.

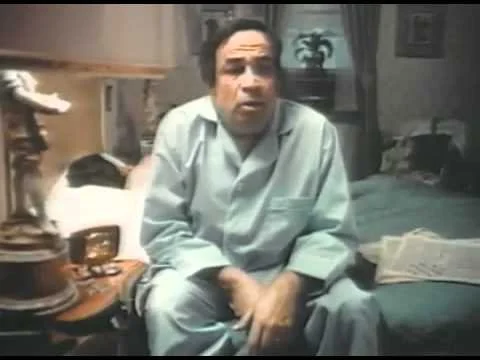

“I can’t believe I ate the whole thing.”

Not to be outdone, DDB did its own Alka-Seltzer ad. Again, a cultural touchstone and a breakthrough — an ad about making an ad.

Bill Bernbach retired in 1976 and died before his campaigns, from “Think Small” to Spicy Meatball won “Ad of the Century” awards. And today, alas, there is no shortage of stupid commercials. But every now and then, the mundane “art” of advertising reaches for a higher level. And along with selling you something, a commercial tells a human story, touches a nerve, or just talks to you like an adult. And then you hear the Mad Man who broke all the rules thinking big.

“Let us prove to the world,” Bernbach said, “that good taste, good art, and good writing can be good selling."