THE GAME OF THEIR LIVES

BELO HORIZONTE, BRAZIL — JUNE 29, 1950 — No eyes of an eager world focused on the soccer squads as they took the pitch that afternoon. But to 30,000 onlookers in this Brazilian mining city, the game looked like a rout.

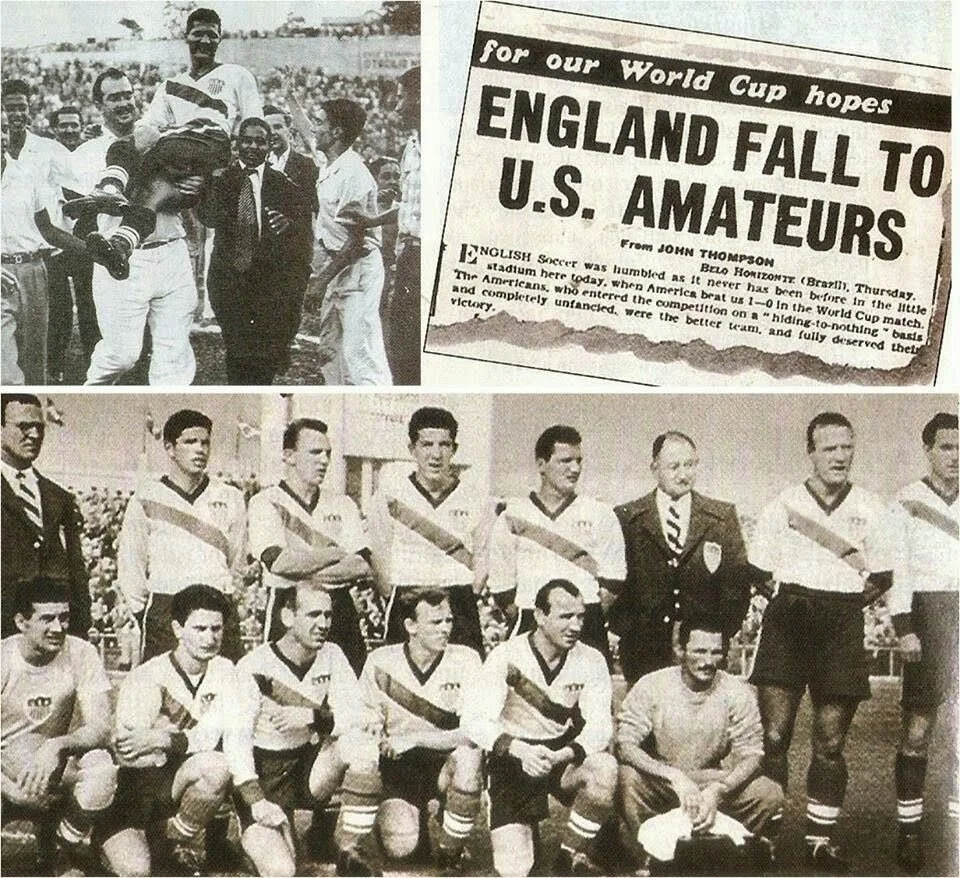

The British were the “Kings of Football,” 3-1 favorites to win the 1950 World Cup and expected to beat the U.S. (500-1 odds) by six goals or more. Hadn’t the Americans lost recent matches by 4-0, 5-0, 11-0? Weren’t they a ragtag band of amateurs?

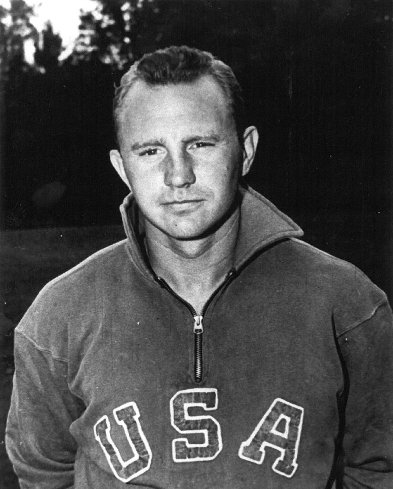

Forward Walter Bahr taught high school in Philadelphia. Forward Joe Gaetjens was dishwasher in Manhattan. The team also included a mailman, a machinist, and a few factory workers. Goalie Frank Borghi, nicknamed “the six goal wonder” for the average score against him, drove a hearse for a funeral home.

“We were playground players,” one recalled in The Game of their Lives. “Like the kids you see today shooting baskets in any park.”

But there was a scrappiness about the Americans, noticed by one reporter. “The Americans came strolling into the dressing rooms in Belo Horizonte, surely the strangest team ever at a World Cup. Some wore Stetsons, some smoked big cigars, and some were still in the happy, early stages of hangovers.“

In the game’s first twelve minutes, England had six shots on goal. Two hit the post, one sailed inches over the crossbar. Frank Borghi saved others with a dive, a leap, a prayer.

Then the Americans brought the ball upfield and took their own shot. England’s goalie gobbled it up but fans came alive, roaring for the Americans. A minute later, Borghi made another diving save. And another. . .

Whether you call it football or soccer, it is the world’s game, “the beautiful game.” The grace, the footwork, the endurance endeared it to every country — except America. In 1950, NO ONE in America played soccer. There was no MLS, no youth soccer, few college teams.

So when the American squad somehow qualified for the cup, the first since 1938 due to World War II, no one cared. The lone American journalist among 400 covering the cup had paid his own way to Brazil.

The exception came in immigrant circles, especially in St. Louis. There, tightly knit enclaves — Germans in Deutschtown, Irish in Dogtown, Italians on Dago Hill — played their hearts out.

“You played for the neighborhood, you played for the Hill,” goalie Frank Borghi remembered. “And because it was fun.”

To the amazement of the crowd, the Americans — four Italians, two Portuguese, one Belgian, an Irish, German, Haitian, and a Scot — kept the score at 0-0 past the 30-minute mark. And then. . . Well, “do you believe in miracles?”

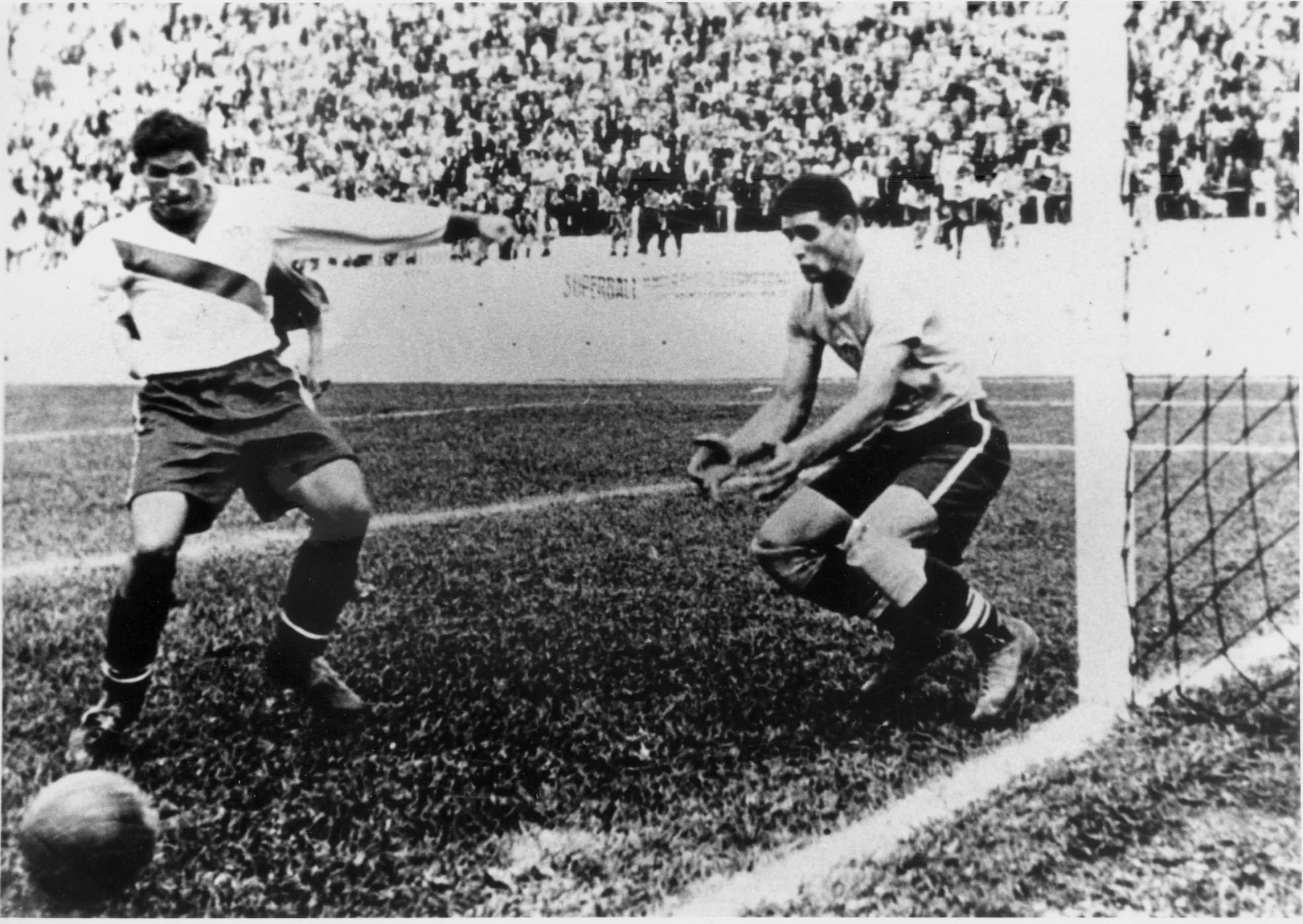

In the 38th minute, the high school teacher took a throw-in at midfield, dribbled 20 yards, then launched a looping pass into the penalty box. The ball looked easy to grab but at the last second, the dishwasher hurled himself head first “as if he thought he could fly,” the mailman recalled. The ball glanced off Gaetjens’ head and into the net.

The roar was deafening. Fathers shielded sons from the noise. The referee plugged his ears.

“Holy Christ,” the mailman told the machinist. “I think we just woke them up. Hold onto your hat, Joe, all hell’s gonna break loose now.”

The score remained 1-0 into halftime. Back on the field, England pressed again and again. The U.S. had another shot that got the crowd chanting: Mais Um, Mais Um (one more.) But the amateurs looked weary.

“We didn’t have the conditioning those guys had,” the mailman remembered. “We were good for maybe twenty, twenty-five minutes before we started to tire.” Five days earlier, the U.S. had led Spain 1-0, only to lose 3-1. No substitutions were allowed in soccer back then, and everyone expected another fadeout, everyone except the “playground players.”

From the 80th minute, England dominated. Shot after shot. Wide by inches. Blocked by a dive, a leap, a prayer. A breakaway run, tackled from behind. A ball kept off the goalline by inches. When the whistle blew, Walter Bahr caught the ball and clutched it to his chest. Thousands surged onto the field, lifting the Americans, frolicking as only World Cup fans can.

Five days later, The U.S. lost to Chile 5-2. When players flew home, no one met them at airports. The upset had made news only in St. Louis. The New York Times got the report, thought it was a hoax, and buried it.

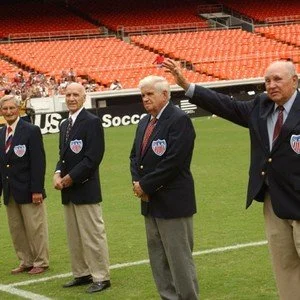

The U.S. did not return to the World Cup until 1990. By then, upstart youth leagues and college programs brought the American team a grudging respect in “the world’s game.”

All those young men from a summer afternoon in 1950 are gone now. But every four years, someone remembers “the greatest upset in World Cup history.” When America’s amateurs not only beat the Kings of Football but reminded them why we play games, after all.

“The way it is today,” Frank Borghi remembered, “you see those guys out there, they got twenty, thirty soccer balls, they’re all serious, they’re doing their fancy drills, their organized calisthenics. Hard to believe they’re havin’ much fun. Us, we were lucky if we had one good ball. And calisthenics? I’d go get in the goalmouth, pick up a few rocks, shake ‘em around a little to loosen up, and it’d be, ‘Okay, I’m ready. Let’s go.’”