TABASCO -- THE LITTLE SAUCE THAT SPICED UP AMERICA

NEW IBERIA, LOUISIANA — From pre-Columbian times, salt was the seasoning on Avery Island. Not an actual island but an enormous dome of salt, this muggy swampland was spiced by Native-Americans, slaves, plantation owners, and the Union soldiers who captured it during the Civil War. Then a new condiment came to conquer the culinary world.

“There are no empty tabasco sauce bottles,” comedy writer Mason Williams once observed. If true, that’s because whenever a bottle is emptied, drop by drop, a new one quickly appears — on kitchen tables, in restaurant booths, on the counters of every damn diner coast-to-coast. Though it has spawned imitators, Tabasco remains the gold standard of hot sauces — a uniquely American product with a uniquely American story.

Edward McIlhenny was not born on the bayou but came here for love. A New Orleans banker, McIlhenny married into Avery Island’s most prominent family — the Avery’s themselves — in 1850. Then one day, a soldier back from the Mexican War handed McIlhenny some bright red peppers. Live dangerously, the soldier said. Or perhaps just, “try ‘em.”

American food, even in the deep South, was bland and bean-ish. Collard greens, butter beans, cabbage. But when McIlhenny chopped up the peppers and sprinkled them on this mush — WOW! Suddenly the sweltering Petit Anse Bayou wasn’t the only heat in these parts. And pepper seeds planted in his garden grew as if in Mexico.

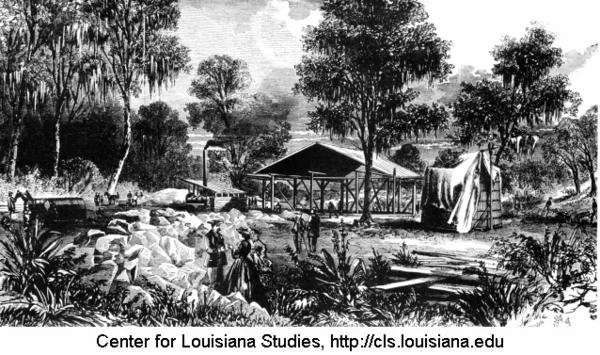

No one knows when McIlhenny began making the sauce, but after fleeing Avery Island during the Civil War, he came home to ruins. Burned buildings. Ravaged crops. But the little red peppers were growing all over. Needing an income, McIlhenny turned to the sauce whose making was as simple as this:

Find the reddest peppers, comparing their color to a bright red stick, aka “le baton rouge.” Chop them up, add salt, and soak the mash in crockery for 30 days. Strain to remove seeds and skins, then add vinegar. Soak another 30 days, later for three years in oak barrels. Open the barrels and stand back. “The smell,” New York Times food writer Craig Claiborne wrote, “is akin to that of newly squeezed tomatoes fresh from the vine.” Bottle and serve, drop by drop.

McIlhenny began collecting old cologne bottles, and from a few dozen filled in 1868, Tabasco was born. McIlhenny wanted to call it Petit Anse Sauce but locals objected, so in 1870, his newly patented recipe read “Tabasco Sauce,” from the region of Mexico where the first peppers came.

Tabasco might have stayed in the Deep South had McIlhenny not given a few bottles to a Union general in occupied Louisiana. The general had a brother back in New York who was a wholesale grocer. Soon Americans from Boston to Nevada, where an ancient Tabasco bottle was recently found in a buried saloon, were asking for “that famous sauce Mr. McIlhenny makes.”

In 1872, hoping to spice up Europe, McIlhenny opened a London office. Come the new century, Tabasco sauce was mentioned in Broadway shows, in cookbooks, in recipes for a new drink called a “Bloody Mary,” Mexico might have its habaneros and jalapeños, Korea its siracha, but America had Tabasco sauce. And every bottle, filled with the sauce still made by hand, came from the little hamlet down on the bayou.

But Avery Island is more than just spice. McIlhenny’s descendants, who still run the company, are ardent conservationists. Shortly after McIlhenny pere died in 1890, one son was appalled by the local slaying of egrets, whose feathers made fine hats. Soon eight young egrets were gathered and protected, then released into the Gulf of Mexico. When they came back the next spring, a migration pattern was begun. It continues to this day, making Avery Island a sanctuary for birds, alligators, live oak trees, and Spanish moss. Even when oil was discovered in 1942, the McIlhennys insisted that pipelines be buried or painted green.

Today, Tabasco remains a family affair, run by the sixth generation of McIlhennys. Some 200 employees pump out 750,000 bottles of sauce each day. Tabasco sauce can be found in Buckingham Palace, on Air Force One, on the International Space Station, and perhaps in your own cupboard.

If imitation is the highest form of flattery, Tabasco is highly flattered. Dozens, perhaps hundreds of hot sauces are now on the market. Seeking to stand out, many have spicy names. Hot Lava. Angry Goat Pepper. Hemorrhoid Helper. Slap Ya Mama. Smack My Ass and Call Me Sally. . .

But there remains only one Tabasco. The original cologne bottles were replaced in 1927 with the slim cylinder still used today. And the original recipe — peppers, vinegar and salt — has never changed. As Amazon reviewers note, why mess with a classic?

— “Put it on everything; no regrets.”

— “Although I’ve heard Tabasco sauce can be used to spark forest fires, kill cockroaches, cure insomnia and remove rust from steel, I purchased it to use in food to add ‘heat’ and flavor. It works just fine for that purpose.”

— ”My husband uses this on everything.”

As they say in these parts, “‘nuff said.”