DOROTHEA LANGE -- BEYOND "MIGRANT MOTHER"

NIPOMO, CA — MARCH 1936 — Two women, exhausted from work, converged in a moment that captured the human condition. But the moment almost didn’t happen.

Weary from a week of touring migrant labor camps, Dorothea Lange was headed home. “Sixty-five miles an hour for seven hours would get me home to my family that night, and my eyes were glued to the wet and gleaming highway that stretched out ahead.”

The sign read PEA PICKERS CAMP. Lange sped past. Didn’t she have enough photos? But mile after mile, she argued with herself.

“Dorothea, how about that camp back there?”

“What is the situation back there?”

“Are you going back?”

Twenty miles on, she could stand it no longer. She did a U-turn, drove back, parked, and went looking.

“I saw and approached the hungry and desperate mother, as if drawn by a magnet. . .”

“Migrant Mother” is an American icon, but Dorothea Lange was no “one-picture photographer.” Drawn to the world’s injustice, Lange pioneered “documentary photography,” turning photo-journalism into high art. And beyond “Migrant Mother,” her photos spotlit humanity in all its hardship and hope.

Lange’s interest in struggle came at an early age. At seven, polio withered her right leg, leaving her with a lifelong limp. “It formed me, guided me, instructed me, helped me, and humiliated me," Lange said. Five years later her parents split, sending Dorothea’s family from Hoboken into Manhattan’s gritty Lower East Side. There, while her mother worked, Dorothea roamed the streets, studying people.

Though she did not own a camera, Lange was drawn to photography and soon studied with a member of Alfred Stieglitz Photo-Secession. In 1918, she set out with a friend to tour the world, but in San Francisco, a robber took all their money. Lange had to stay and work. She started in a photo studio.

Soon married with a son, Lange rose through the 1920s, running her own photo shop taking portraits of rich socialites. Then one week in 1929, the riches vanished.

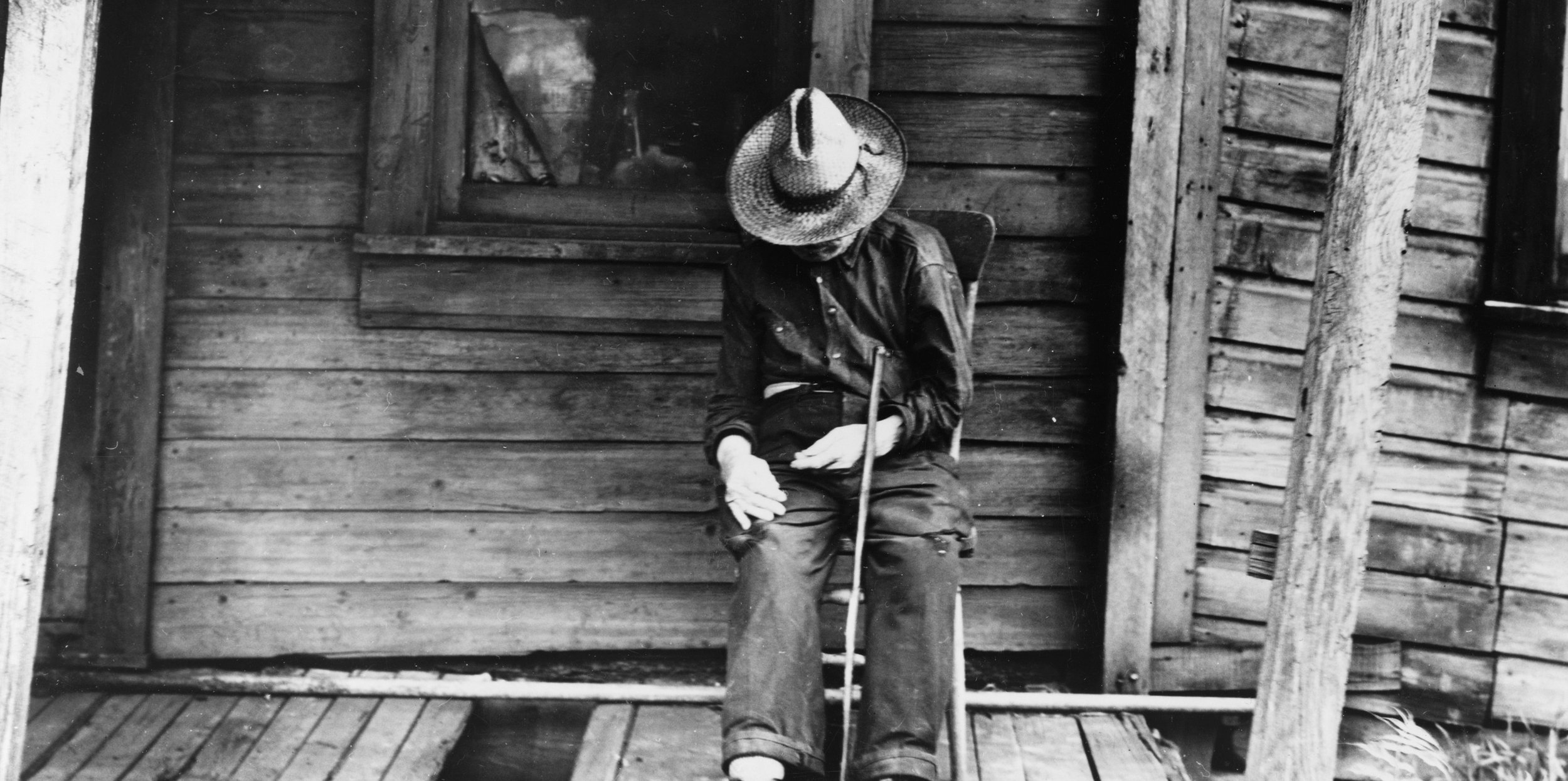

Looking out her studio window, Lange saw desperate, hungry people roaming the streets, sleeping on sidewalks, lining up for bread. One afternoon in 1932, she left the studio and began taking photos. “Five years earlier I would have thought it enough to take a picture of a man, no more. But now, I wanted to take a picture of a man as he stood in his world.”

One of Lange’s first shots was at a bread line run by a woman locals called the White Angel. When “White Angel Bread Line” ran in newspapers, it earned Lange a job with the New Deal’s Resettlement Administration.

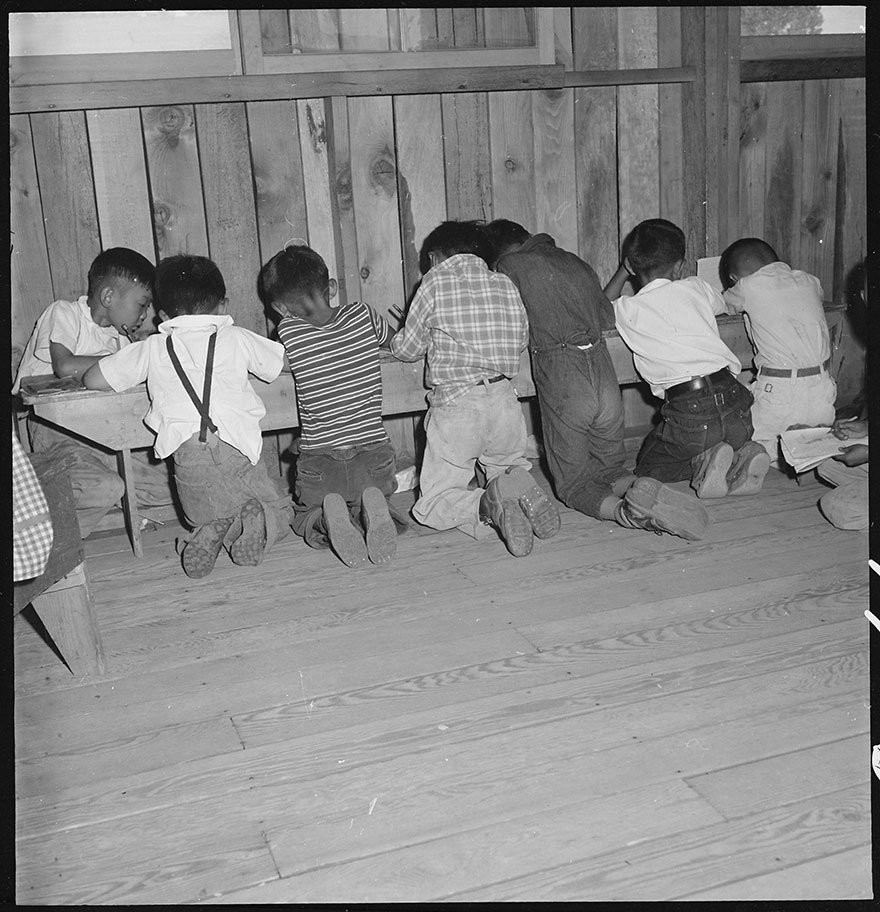

“No one was ever given exact direction,” she recalled. “You were turned loose in a region. And the assignment was — see what is really there. What does it look like? What does it feel like? What actually is the human condition?”

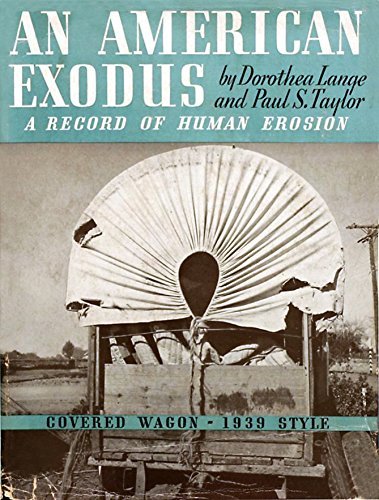

Some 300,000 Dust Bowl refugees had poured into Central California, seeking work, dignity, a life. Alone, Lange began touring migrant camps. After a divorce, she married a Berkeley economist and they spent five years on the road, he compiling data, she capturing hardships in full face. Her photos ran in newspapers, some alongside an article, “The Harvest Gypsies,” by a young journalist named Steinbeck. In 1939, the year Steinbeck turned his stories into The Grapes of Wrath, Lange published An American Exodus.

“You see these American faces, strong, spare, anxious,” one reviewer wrote. “You will find it hard to forget this material of human erosion.”

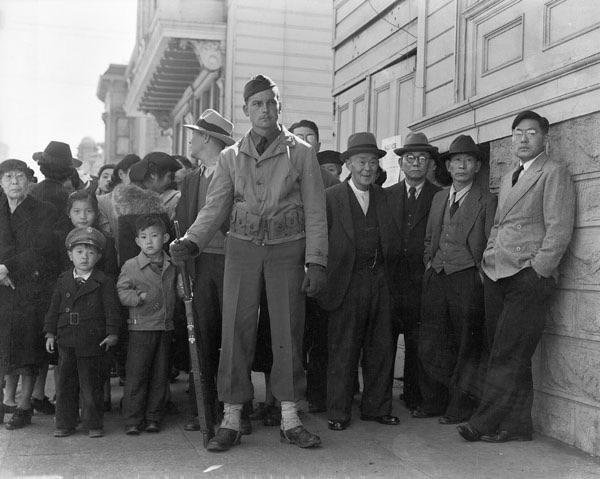

Lange won a Guggenheim to study abroad but renounced it when World War II began. Photographing the home front — shipyards, street scenes, more migrants — she was drawn to another human tragedy.

Under Executive Order 9066, 100,000 Japanese-Americans were rounded up and put into camps. From their identification tags to their faces, innocent and bewildered, Lange documented the outrage. Touring the camps, she settled in rural California at Manzanar She was appalled.

Here were people living in horse stalls. Here was hunger, despair, suicide. Lange was forbidden to photograph barbed wire or armed guards but her photos were still considered too harsh for public viewing. All were stored in the National Archives until 2011 when 800 were discovered and published in Impounded.

After the war, Lange continued to photograph “the deprived, the dislocated, the rootless.” She started the magazine Aperture, taught with Ansel Adams, and held fast to her faith in humanity, a faith that emerged in faces.

“The human face is the universal language. The same expressions are readable, understandable all over the world.”

And the Migrant Mother? In 1978, thirteen years after Lange’s death, Florence Owens Thompson stepped forward to tell her story. She rather resented the ubiquitous photo of despair and defeat. Because Thompson, widowed, mother of six, had raised her children by picking cotton, 400 pounds a day. After that moment in 1936, she had moved on to work throughout the Depression and the war.

In 1983, when news spread that the “Migrant Mother” had cancer, strangers sent her $30,000 for health care. The face, the moment, the two women were linked.

“The woman in this picture,” Lange said, “has become a symbol to many people; until now it is her picture, not mine.”