GRAND DAME OF THE GLADES

SOUTH FLORIDA, 1969 — For decades, the riches of the Everglades flowed into the sprawl of greater Miami. Gorgeous tropical birds — egrets, herons, and cranes — were slaughtered to make women’s hats. Canals, dikes, and drainage projects cut the giant wetlands in half. Sugar plantations spread. And then as Miami continued to boom, developers planned an enormous airport on the edge of the glades.

America’s rising green movement denounced the project. The New York Times called it “a blueprint for disaster.” Reams of studies, reports, and newsprint argued the issue, but plans proceeded. Then, a slight, old woman in a floppy hat went to work.

"In the history of the American environmental movement,” the London Independent wrote, “there have been few more remarkable figures than Marjory Stoneman Douglas.”

She came to Florida when wetlands were more common than hotels. Visiting Tampa at age four, she remembered picking an orange. That was in 1894, when the entire state had a half-million people. Then it was back to Massachusetts for more snow and ice, much of it in her own home where her parents fought, separating when she was six.

She might not have returned to Florida but for her own disastrous marriage to a con man who was already married. In 1915, Douglas fled to Miami (pop. 5,000), where her father ran a small newspaper. There she began a “change from a near frigid to a tropical attitude of mind.”

Rising from journalism’s “pink ghetto,” the society page, Douglas became an assistant editor of what would become the Miami Herald. Throughout the 1920s, when developers turned swampland into prime real estate, bringing tens of thousands to South Florida, Douglas saw promise and threat.

“There must be progress, certainly,” she wrote. “But if, in the name of progress, we want to destroy everything that is beautiful in our world, and contaminate the air we breathe and the water we drink, then we are in trouble.”

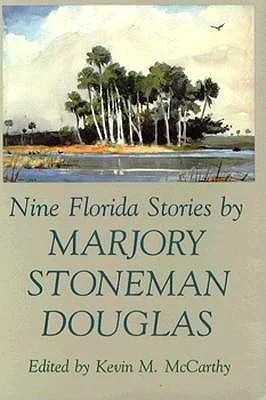

On into her fifties, Douglas published short stories in magazines and profiles in Miami papers. Then in 1942, for a series of books on American rivers, she was asked to profile the Miami River. Complaining that the river was “about an inch long,” she traced its source and fell in love with the Everglades. Five years of research led to her first book. It began “There are no other Everglades in the world.”

Where others had seen an “abominable pestilence-ridden swamp,” Douglas saw unfathomable beauty. “The miracle of light pours over the green and brown expanse of saw grass, and of water, shining and slowly moving; the grass and the water — that is the meaning and the central fact of the Everglades. It is a river of grass.”

The Everglades: River of Grass swept through Florida like the fires that had burned the Everglades after another drainage project. Selling a half million copies, sparking debates, the book presaged Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring. Yet “progress” persisted.

Throughout the 1950s, the Central and Southern Florida Flood Control Project dredged 1,400 miles of canals through the Everglades. Sugar plantations dumped pesticides. Then, when Douglas was 79 and ready for retirement, came plans for an airport.

Douglas spent her 80s touring Florida, speaking to chambers of commerce, politicians, and developers. Some called her a “damn butterfly chaser,” but everyone was captivated.

“She had a tongue like a switchblade and the moral authority to embarrass bureaucrats and politicians and make things happen."

“She would give these wonderful, curmudgeonly speeches to which there was no response. You can't holler back to grandmotherly scolding. All you can do is shuffle your feet and say, 'Yes, Ma'am.'

“The Everglades is a test,” Douglas told Florida. “If we pass it, we may get to keep the planet.”

We passed, sort of. Though the Everglades remains fragile, the airport was never built. One dike was taken down, and further restoration projects struggle to protect the river of grass. But Douglas did not stop.

On into her 90s, she continued to speak. “I’ll speak about the Everglades at the drop of a hat,” she said. In 1983, when homeowners booed her for opposing a drainage plan, she shouted back. “Can't you boo any louder than that? Look. I'm an old lady. I've been here since eight o'clock. It's now eleven. I've got all night, and I'm used to the heat."

Seven years later, in lieu of a 100th birthday party, Douglas asked Floridians to plant trees. Some 100,000 were planted.

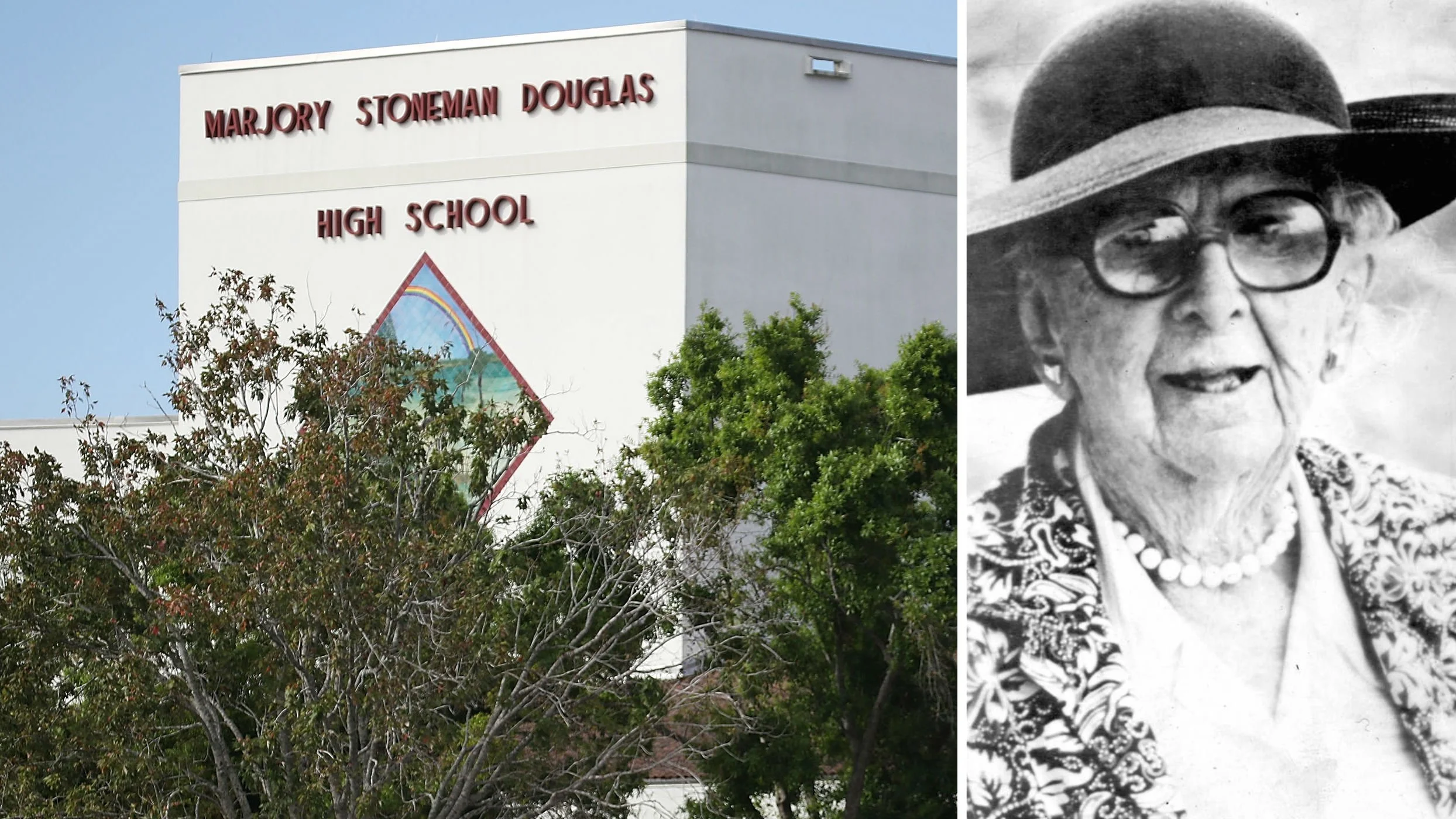

When Douglas died at 108, her ashes were scattered over the Everglades. But her name lived on in eponymous buildings, nature centers, and one high school.

If the name sounds familiar, it comes from tragedy. In 2018, yet another school shooting claimed 17 lives at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida. But the wake of the slaughter brought more than the usual hand-wringing. Students began speaking out. Under the banner “Never Again MSD,” dozens toured America, registering young voters, calling for sensible gun control, organizing a nationwide “March for Our Lives.”

They had learned their lessons well, lessons taught by the woman whose name was on the wall.

“Be a nuisance where it counts. Do your part to inform and stimulate the public to join your action. Be depressed, discouraged, and disappointed at failure, and the disheartening effects of ignorance, greed, corruption, and bad politics — but never give up.”