JACKIE SAVES GRAND CENTRAL

BENEATH MANHATTAN — Bound not for glory but for Midtown, this train rumbles below the city south of Harlem. Dark tunnels echo with the clatter of rails, the screech of brakes. When the train stops, you exit onto a steamy platform and shuffle, as if approaching the Gates of Hell, towards a light in the distance. You step through the portal and. . .

Like the sky itself, the astonishing Grand Central Main Concourse soars above. Light pours in from enormous arched windows. People scurry to catch trains but others stare, gawk, lift their gaze to where the signs of the zodiac stretch across a vast turquoise ceiling.

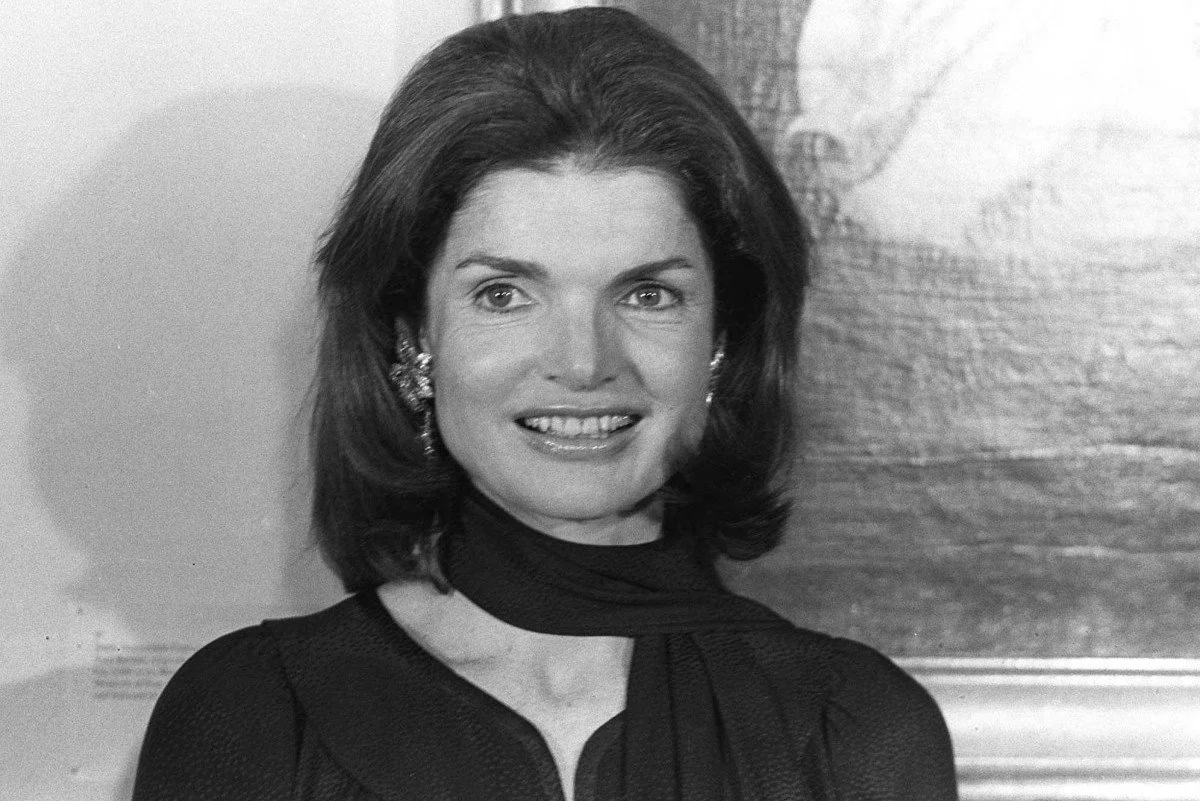

Grand Central is “one of the grandest spaces the early 20th century ever enclosed.” Opened in 1913, the station remains vibrant, active, amazing. Yet a half century ago, this wonder was nearly destroyed. Among its saviors was a woman whose name you might recognize.

By 1975, when Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis settled full-time in Manhattan, Grand Central seemed doomed. Its owners, the Penn Central Railroad, had grandiose plans. A decade earlier, Penn Central had demolished Penn Station, replacing its fabulous wrought-iron concourse with a cramped terminal squashed beneath Madison Square Garden.

“One entered the city like a god,” architecture critic Vincent Scully wrote of the demolition. “One scuttles in now like a rat.”

For decades, New Yorkers had watched in silence as old mansions and hotels fell to the wrecking ball. But Penn Station’s demise sparked a backlash. A new Landmark Law allowed the city to stop the destruction of major landmarks. One of the first listed was Grand Central.

But since its heyday, cars and planes made train travel seem quaint. By 1975, Grand Central was a tomb, its ceiling browned by smoke, its windows grimy, its concourse filled with drug dealers and the homeless. When Penn Central challenged the Landmark Law, the state Supreme Court sided with developers. The demolition, the court ruled, created “no reaction here other than that of a long neglected faded beauty.”

A 55-story building would soon swallow the station. The Main Concourse would be gutted, the Beaux-Arts facade demolished. Jackie was outraged.

As First Lady, she had presided over restoration of the White House. Later she helped preserve D.C.’s Lafayette Square, and parts of her hometown of Newport, R.I. Now, as the most famous woman in America, she lent her prestige to Grand Central.

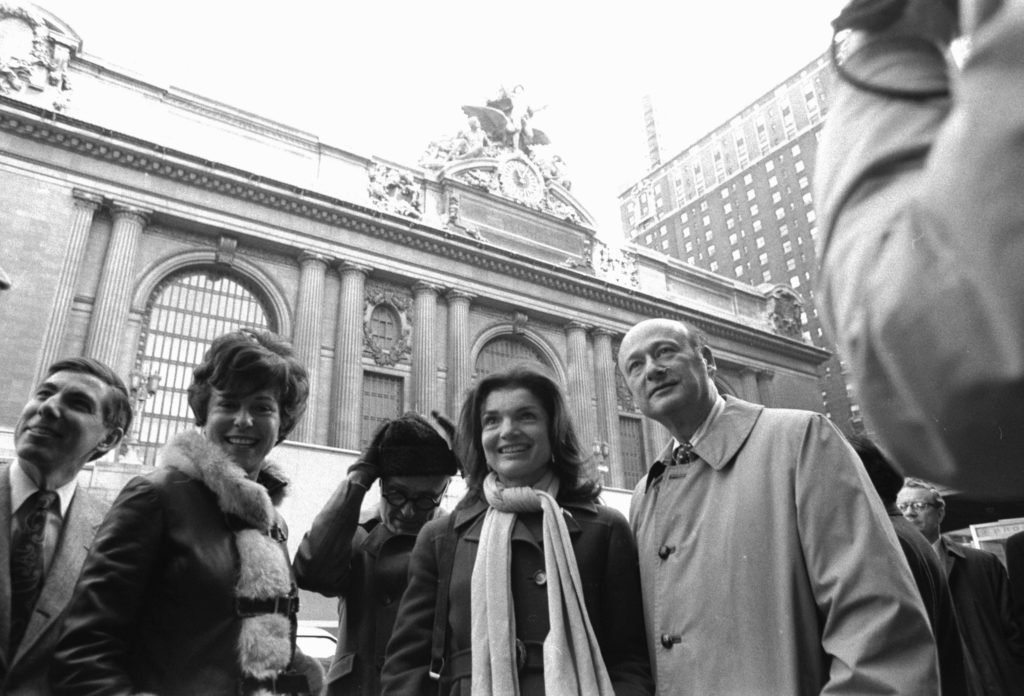

On January 30, 1975, the Municipal Arts Society of New York held a press conference at the Oyster Bar in Grand Central. Politicians and promoters mingled, but the star of the show, the one everyone wanted to meet, was Jackie. When she spoke, her lilting voice seemed to come from some distant Camelot, but with a dire warning.

“If we don’t care about our past we can’t have very much hope for our future. We’ve all heard that it's too late, or that it has to happen, that it's inevitable. But I don’t think that's true.”

A week later, New York Mayor Abe Beame got a hand-written letter on powder blue stationery. With New York on the verge of bankruptcy, development was essential. Beame had said nothing about Grand Central.

“Dear Mayor Beame,” Jackie wrote. “Is it not cruel to let our city die by degrees, stripped of all her proud moments, until there is nothing left of all her history and beauty to inspire our children? If they are not inspired by the past of our city, where will they find the strength to fight for her future?”

Within days, calling Grand Central “a symbol of life in the City of New York,” Beame joined the battle. Jackie then teamed with architect Phillip Johnson to form the Committee to Save Grand Central. “Europe has its cathedrals,” Johnson noted, “and we have Grand Central Station. Europe wouldn’t put a tower on a cathedral.”

The city appealed the state’s decision, won, and the battle went to the U,S. Supreme Court. On the day the court began deliberations, Jackie and other preservationists rode the “Landmark Express,” a chartered Amtrak train to Washington, D.C. Supporters boarded along the route and were soon singing, “Let’s make a grand, grand stand for Grand Central, for the good old U.S.A.”

Two months later, by a 6-3 vote, the Supreme Court saved more than a faded old train station. Some 500 landmark laws stood to fall if Grand Central did. Writing for the majority, Justice William Brennan noted, “Historic conservation is but one aspect of the much larger problem, basically an environmental one, of enhancing—or perhaps developing for the first time—the quality of life for people."

Grand Central was saved, but the terminal was still a wreck. Only in the 1990s did restoration begin. Windows were cleaned, new marble added, concourses revived, and above all, literally, the entire arched ceiling and its constellations were stripped, scrubbed, made to sparkle again.

On October 1, 1998, Grand Central re-opened. Stepping into the Grand Concourse, thousands of jaded New Yorkers paused, looked up, and became children again.

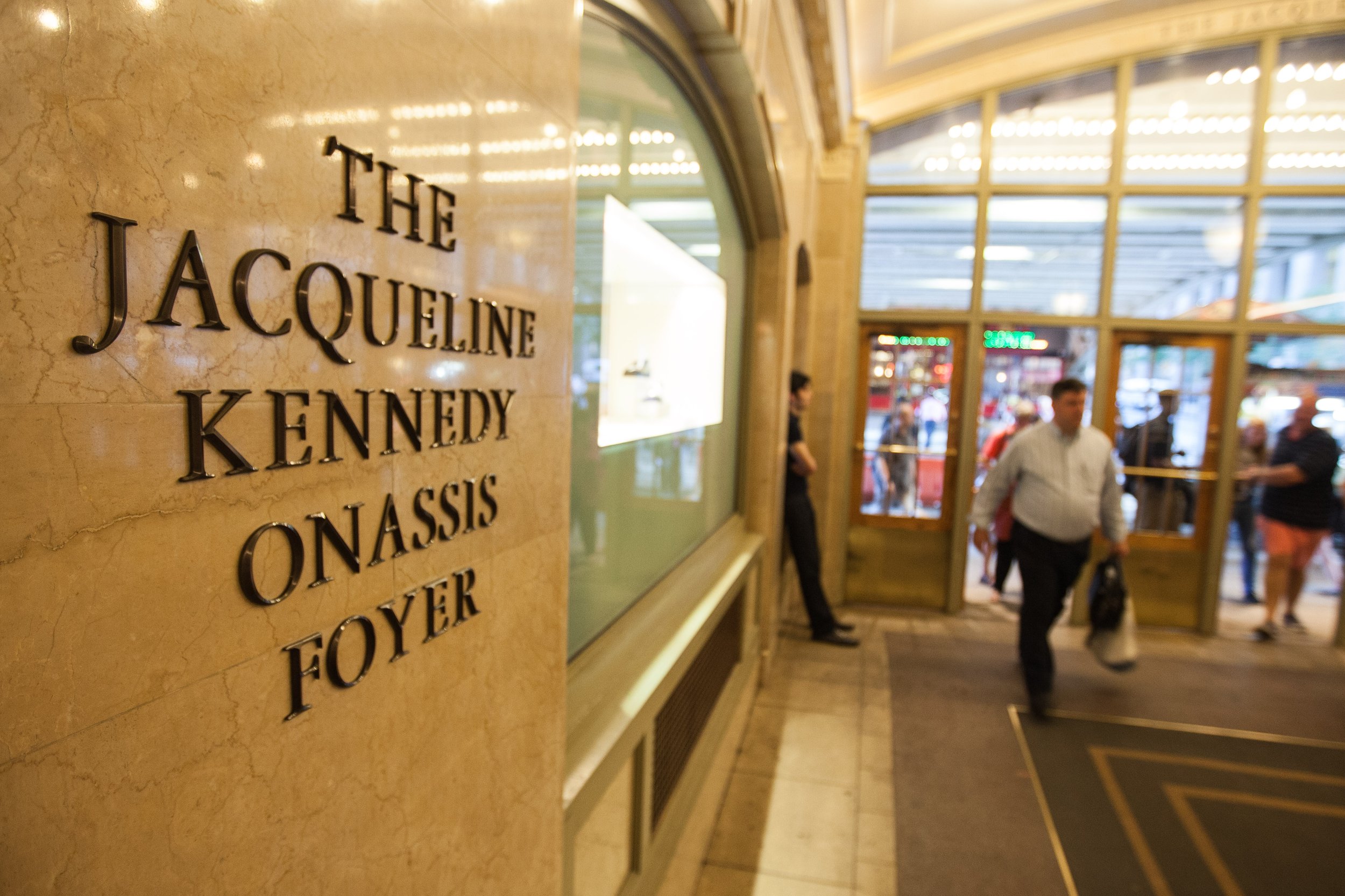

These days, Grand Central glitters with chandeliers, polished marble, and pure panache. But it’s also a train station where thousands pass through each day. Most just hurry on but some pause in the Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis Foyer to learn of how Jackie saved Grand Central.