HERE COME THE SUN QUEEN

DOVER, MA — WINTER 1949 — In this Yankee village of colonial and Cape homes, the new house on the block is an eyesore. Odd, angular, and shockingly modern, it “might as well have been dropped in the middle of a field by aliens,” one resident recalled.

But every day dozens line up for tours. Ushered inside, they marvel at the huge windows, the fans, but mostly the heat. Month after month, throughout the coldest New England winter, the house’s heat comes solely from the sun.

“It is the things supposed to be impossible that interest me,” the Sun Queen said. “I like to do things they say cannot be done.”

Today, as upstart solar is finally gaining ground against Big Oil, it’s hard to remember a time when the sun had a P.R problem. Solar power is too fleeting, skeptics said. Solar power is a dream. Oil, gas, electricity, even nuclear — these are the energies that pay. Maria Telkes disagreed.

Telkes came to engineering the hard way — as a woman. Born in Hungary in 1900, she entered college at age 16 and earned her Ph.D. at 24. A year later, she moved to America.

Telkes worked at Westinghouse, designing thermocouplers, little gizmos that convert heat to electricity. But during the Depression, learning of a budding solar program at M.I.T., she wrote to the department. By 1939, she was teaching there and studying M.I.T. Solar #1.

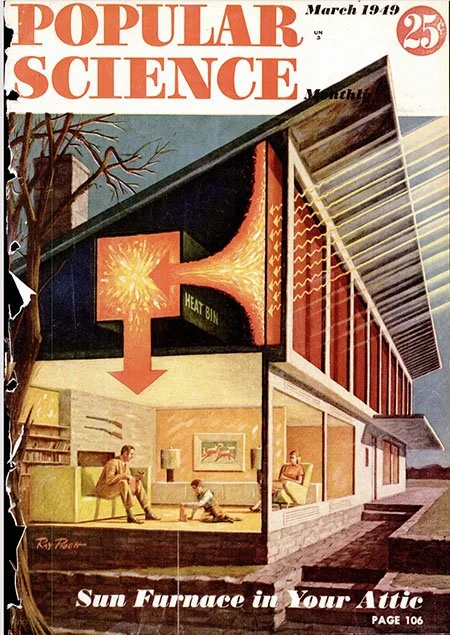

This (mostly) solar-heated house, like later passive solar systems, used flat panel collectors on the roof. Heated water was stored in a huge underground vat, then fanned through the house. The public was curious. “No idea of the last 30 years has so fired the imagination of the American public as the one of letting the old Sol reduce the winter fuel bill,” wrote House Beautiful.

But M.I.T.’s head engineer was skeptical.

“When we started we had high enthusiasm,” Hoyt Hottel remembered. “But we slowly came to realize that while there were uses of the sun, they were not as promising as we all thought they would be."

For the next decade, Telkes and Hottel fought over solar’s promise. Hottel, a Midwestern engineer with more interest in profit than potential, thwarted Telkes at every turn.

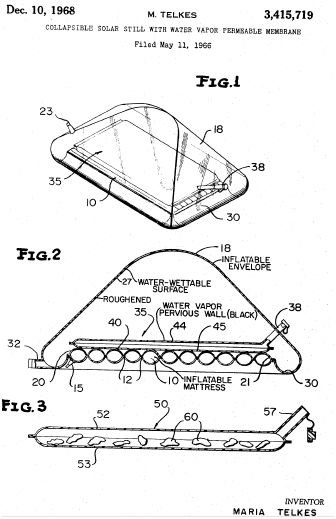

During World War II, Telkes designed a solar-powered desalination device, enabling soldiers on Pacific islands to make fresh water. Hottel delayed its release. Whenever Professor Telkes touted the sun’s untapped energy, Professor Hottel scoffed.

“Figures such as these are almost irrelevant to the problem of practical utilization of solar energy,” he said. “They have attracted uncounted crank inventors who have approached the problem with little more mental equipment than a rosy optimism.”

But one “crank investor” was a Boston brahmin, Godfrey Lowell Cabot. Despite making his fortune in industrial chemistry, Cabot saw the sun’s potential, and his funding helped Telkes research alternatives to passive solar.

Glauber’s salt (sodium sulfate) begins to melt at 90 degrees F. And as it melts, it slowly releases the stored heat. Telkes was soon designing an entire home heated by this special salt.

While Hottel stayed with flat panels, Telkes worked with architect Elizabeth Raymond to build the Dover Sun House. When the house opened I 1949, the press called Telkes “the Sun Queen.” This “attractive blonde Hungarian scientist,” was “the world’s foremost authority on solar science for heating.” And her Sun House was a miracle.

LIFE headlined — “A New House in Dover, Mass., Has Been Comfortably Warm All Winter Without a Furnace.” Popular Science considered the house more important than the Bomb. But back in the lab, men remained skeptical.

“We’re kidding the public about the sun,” Hoyt Hottel said. “It’s not worth as much as claimed.”

The Dover Sun House had a limited shelf life. Glauber’s salt corroded its tanks, which leaked, reducing heat supply. By 1954, the house needed a full heating system. By then, drawing suspicion as an “ultra radical,” as a Hungarian in the age McCarthyism, and of course, as a woman, Telkes had been dismissed from M.I.T.

But the Sun Queen persisted.

Telkes went on to teach at NYU and design solar ovens and solar houses in Manhattan and Princeton. Then in 1971, she and colleagues at the University of Delaware built Solar One, the first house to blend passive solar with the newest tech — photovoltaics.

Eight years later, President Jimmy Carter put solar panels on the White House roof. “In the year 2000,” Carter announced, “this solar water heater behind me will still be here supplying cheap, efficient energy.” Carter was wrong. President Reagan had the system removed.

When the Sun Queen died in 1995, solar energy was still reeling from the Reagan years. This “road not taken,” wrote Bill McKibben, was “an unspeakable tragedy.”

Telkes’ Solar House is gone now but Dover now sports an enormous solar field. And 20 percent of Massachusetts’ electricity is from solar. (The Attic has been all solar since 2019.)

Proven prescient, Maria Telkes is finally getting the respect she deserves. In 2012, as holder of 20 patents, she was inducted into National Inventors Hall of Fame (along with Steve Jobs). Last month, Google changed its daily logo to honor her. And in April, PBS will feature her in a prime-time documentary.

Solar energy, the Sun Queen wrote in 1951, is “the cleanest and healthiest fuel Sunlight will be used as a source of energy sooner or later anyway. Why wait?”