FINDING ZORA

FORT PIERCE, FL — AUGUST 1973 — The graveyard is a jungle, a tangle of weeds, snakes, and gravestones toppled or trampled. Into this swamp of amnesia steps a young author in search of time.

Though Alice Walker has yet to write The Color Purple, her first novel and poems have set her on the road to literary acclaim. Now she wants to repay the woman whose novels, though unknown to the rest of America, made her own possible.

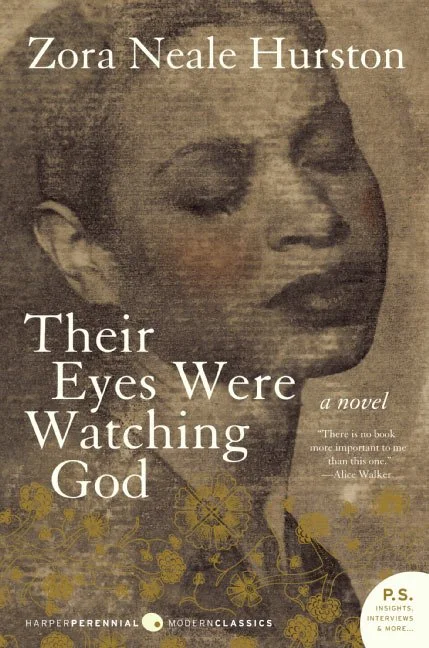

If stranded on that proverbial desert island with just ten books, Walker often said, two would be works by Zora Neale Hurston. When friends asked, “Who?” Walker explained that Hurston’s book of folklore, Mules and Men, would let her “pass on to younger generations the life of American blacks as legend and myth.” And of Hurston’s Their Eyes were Watching God, Walker wrote, “there is no book more important to me than this one.”

But where is Zora?

The day is sweltering, the insects swarming. Rosalee, the woman in the graveyard office. is no help. The grave must be out here — somewhere. Finally, Walker begins calling.

“Zora!” I yell as loud as I can. “Zora, are you out here?”

“If she is,” Rosalee says, “I hope she’ll keep it to herself.”

America now knows Zora Neale Hurston as a leading light of the Harlem Renaissance. A brilliant prose stylist, her four novels, plus 50-some stories and essays reveal a blithe spirit, proud, curious, often dazzling.

“I am not tragically colored,” she wrote in How it Feels to be Colored Me. “There is no great sorrow damned up in my soul, nor lurking behind my eyes. . . I do not weep at the world. I am too busy sharpening my oyster knife.”

In 1925, after rising from teenage maid to student at Howard and Barnard, Hurston charmed Harlem with her wit, style, and sass. “She is a perfect book of entertainment in herself,” Langston Hughes wrote. “She was full of side-splitting anecdotes, humorous tales, and tragicomic stories. She could make you laugh one minute and cry the next.”

READ FIVE EXCERPTS FROM ZORA NEALE HURSTON ON “THE DUSTY BOOKSHELF”

During the Depression, Hurston’s novels got mixed reviews and sold poorly. Undaunted, she continued to write and to pursue her other passion. Collecting black folktales, she traveled throughout the South, to Haiti, and later to Honduras. But by the mid-1940s, her star was sinking.

After one last novel in 1948, Hurston struggled. Magazines contracted articles but she rarely finished them. She briefly taught high school, worked as a librarian, a newspaper reporter, a maid. Living alone in small apartments, she worked on a final novel about King Herod, also unfinished.

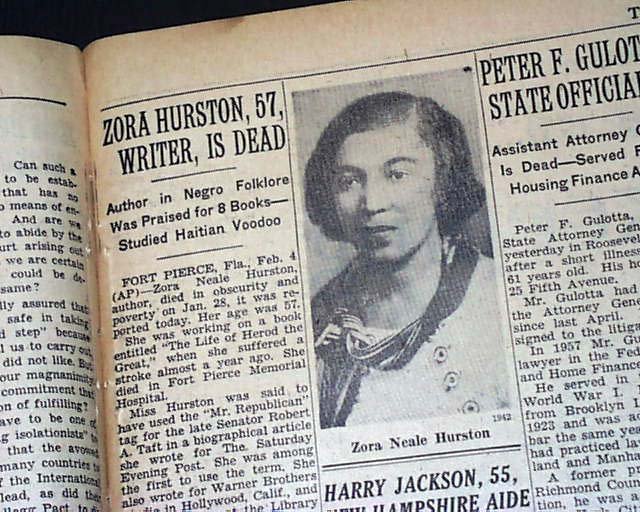

In the late 1950s, Hurston ended up on welfare. A stroke landed her in the hospital and, after moving to a county welfare home, another stroke killed her. Aside from her voluminous papers, a typewriter, and a kerosene lamp, she had nothing.

“I am not materialistic,” she wrote to one of three ex-husbands. “If I happen to die without money, somebody will bury me.”

When news of her death spread, friends took up a collection. $661 bought a grave but no headstone. A hundred people attended the memorial service. Then Zora, “an iridescent personality of many colors,” lay forgotten beneath the spreading weeds.

“I know that nothing is destructible; things merely change forms,” she had written. “When the consciousness we know as life ceases, I know that I shall still be part and parcel of the world.”

“Zo-ra!” Alice Walker shouts again. Just then her foot sinks into a hole. Six by three feet. A grave. Further research identifies this as the spot. Walker soon has a headstone made.

Comebacks are hard to plan. Fallen on hard times, every human effort aims at revival, yet the world moves on, forgetting if not forgiving. Revival hinges on chance, circumstance, and the eternal talent of the fallen.

So when Alice Walker’s article, “In Search of Zora Neale Hurston” appeared in Ms. in 1975, legions of readers asked “Who?” then went on their own search. What they found was the remarkable novels of a remarkable woman. And word spread.

In 1977, the first biography (of several) portrayed the Zora who had charmed Harlem and all those folks who told her their stories. Her four novels were soon back in print. Their Eyes Were Watching God has since sold more than a million copies and been translated into a dozen languages. The Library of America has two volumes of Hurston’s works.

READ FIVE ZORA NEALE HURSTON EXCERPTS ON “THE DUSTY BOOKSHELF”

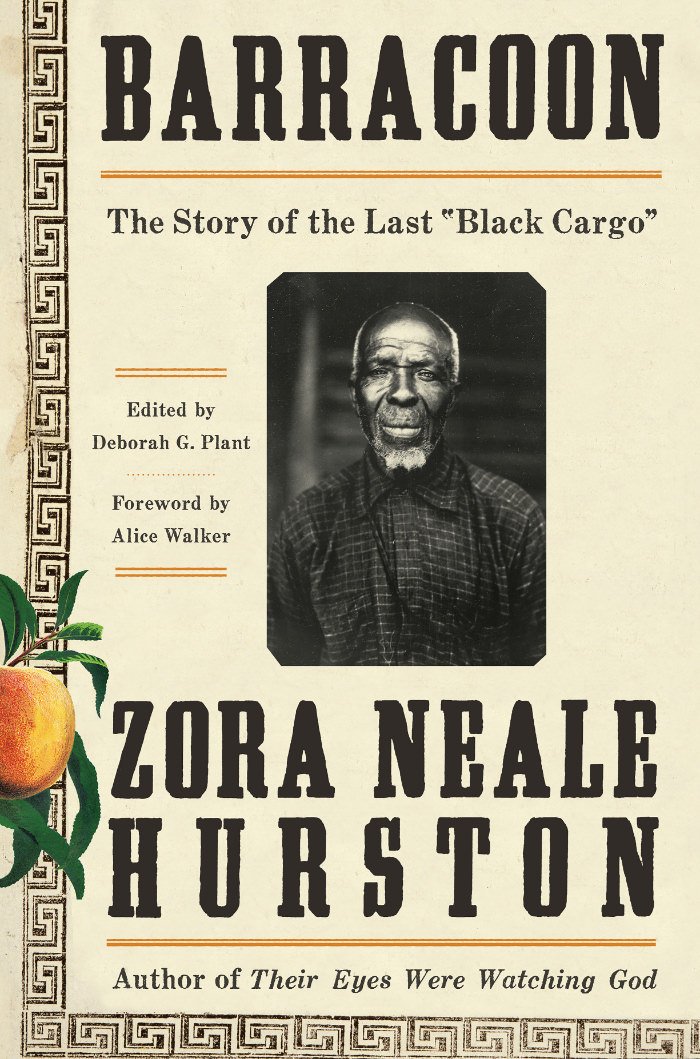

“Mule Bone,” her play co-written with Langston Hughes, appeared on Broadway in 2002. The Smithsonian published Zora’s folk tale collection, Every Tongue Got to Caress. And in 2018, Barracoon, recounting her interviews with the last slave brought to America — illegally in 1859 — became a bestseller.

Zora’s grave has since been cleaned up and is part of a regional “Dust Tracks” tour tracing Zora’s life in Florida. But although she died poor, she did not die dispirited. She rarely doubted her talent, nor did she ever write for fame or money. She wrote as she danced, to celebrate.

“I have known the joy and pain of deep friendship. I have served and been served. I have made some good enemies for which I am not a bit sorry. I have loved unselfishly, and I have fondled hatred with the red-hot tongs of Hell. That’s living.”