COMEBACK ON THE CUYAHOGA

CLEVELAND, JUNE 22, 1969 — On that sunny summer day when the river caught fire, teenager Gene Roberts remembered the afternoon, years earlier, when he fell into the Cuyahoga.

“I thought I might die,” he said. After swimming and slogging through the oily muck, Roberts dragged himself onshore. As he walked home, his stench kept friends far upwind. And now the river was on fire — again.

As river fires went, this was small. Crews spent just a half-hour dousing the flaming sewage. The blaze did not make local headlines. Ho-hum, the river’s burning again.

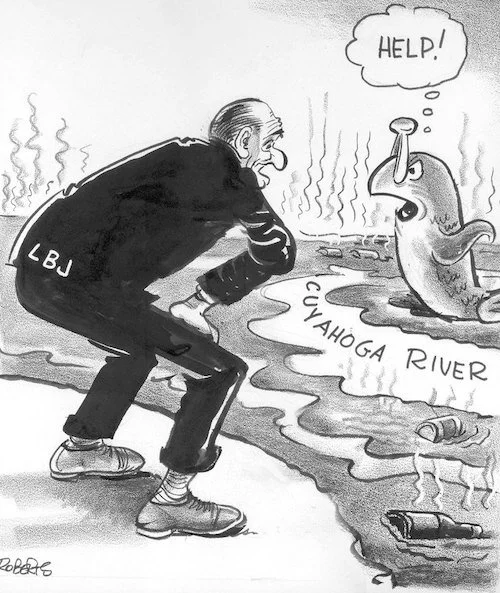

But the 1969 burning of the Cuyahoga “was a spark plug for environmental reforms around the country,” one EPA official recalled. Because unlike previous fires on Cleveland’s river, this one blazed through an America starting to go green.

Randy Newman soon mocked the Cuyahoga, singing, “Burn on, big river, burn on.” A documentary, narrated by James Earl Jones, spread the alarm. And TIME, in a widely-read issue that included “one small step for man,” made the Cuyahoga a symbol of America the Ugly.

“Some river!” TIME wrote. “Chocolate brown, it oozes rather than flows." People who fall into the Cuyahoga, “don’t drown but decay.”

Fifty-some years later, longtime Cleveland residents hardly recognize the river. The Cuyahoga has become a symbol of American revival. The 22-mile stretch between Akron and Cleveland, dead to all life in 1969, now hosts 44 varieties of fish. The Cuyahoga is lined with restaurants and bars. Boats and kayaks ply its waters. And on anniversaries of the 1969 burning, Clevelanders come out to celebrate the river they helped to revive.

“It’s just remarkable,” said Steve Tuckerman of the Ohio EPA. “I never thought I would see in my lifetime, let alone in my career, such an amazing comeback of a river.” So how did the Cuyahoga go from tinderbox to clear sailing? The comeback was sparked by shame, local initiatives, and the legislation the Cuyahoga fire inspired, the Clean Water Act.

Though it burned for just a half hour, the Cuyahoga’s timing was perfect. America’s environmental movement was just picking up steam. The first Earth Day was in the planning stages. Joni Mitchell sang “you pave paradise. . .” Neil Young saw “Mother Nature on the run in the 1970s.” (This list could go on.)

Yet it took more than songs to spark the revival. “This didn’t happen because a bunch of wild-haired hippies protested down the street,” another Ohio EPA official said. “This happened because a lot of citizens up and down the watershed worked hard for forty years to improve the river.”

The work began with lawsuits. A dozen huge industrial plants were belching into the Cuyahoga, while hundreds more were turning Lake Erie into what TIME called “a gigantic cesspool.” But environmental legislation was thin, weak, local.

Enter the EPA. Established in December 1970, the Environmental Protection Agency quickly proposed federal laws to control water pollution. The EPA sued Jones and Laughlin Steel for spewing cyanide into the Cuyahoga. Other lawsuits followed. It was a start.

The following summer, Maine Senator Edward Muskie filed the Clean Water Act. Its goals: “1) to make all U.S. waters fishable and swimmable by 1983;” 2) "to have zero water pollution discharge by 1985;" and 3) "to prohibit discharge of toxic amounts of toxic pollutants.”

The bill sailed through Congress but was vetoed by President Nixon. Congress handily overrode the veto and the Clean Water Act became law in October 1971.

The CWA tightened laws on toxic discharge, requiring a permit to spew anything into any “navigable waterway.” Mandated reassessment every three years checked compliance. States, cities, and Native-American tribes got the power to set their own clean water criteria. Ordinary citizens were allowed to sue polluters, and the feds ponied up funds for water treatment plants, up to 75 percent of construction cost.

Fueled by federal action, Cleveland got busy. The regional sewer district spent $3.5 billion, even building tubes beneath the city to hold sewage runoff until it could be treated. In 1974, President Gerald Ford designated the Cuyahoga Valley National Recreation Area, a park preventing development along the river between Akron and Cleveland.

Cleanup continued, yet the waters of the Cuyahoga, which Randy Newman saw “smokin’ through my dreams,” were still choked by dams where pollutants festered. Then in 2005, dam removal began.

On June 22, 2009, when hundreds turned out for the 40th anniversary of the river fire, all were astonished. Beavers, blue herons, and bald eagles nested along the riverbank. Waters flowed clean and blue. Over the next decade, five dams were removed, revealing waterfalls and canyons long hidden.

Few pretend that American waterways are as clean as they should be. More than half have yet to comply with the Clean Water Act. Recent Congresses and the Supreme Court have weakened the act, and the Cuyahoga is still dirtied by urban runoff and occasional spills.

Yet in 2019, the American Rivers Association named the Cuyahoga its “River of the Year.” That same year, the Ohio EPA declared all fish caught in the river “safe to eat.” “The Cuyahoga River still has some issues,” one environmentalist said, “but flammability isn’t among them.”

Gene Roberts now goes fishing along the Cuyahoga. He often hauls in a meal’s worth in a half-hour. “It’s a miracle,” he says. “The river has come back to life.”