SWEET HONEY'S ENDURING ROCK

(NOTE: This article was published in February 2023. Bernice Johnson Reagon passed away on July 19, 2024.)

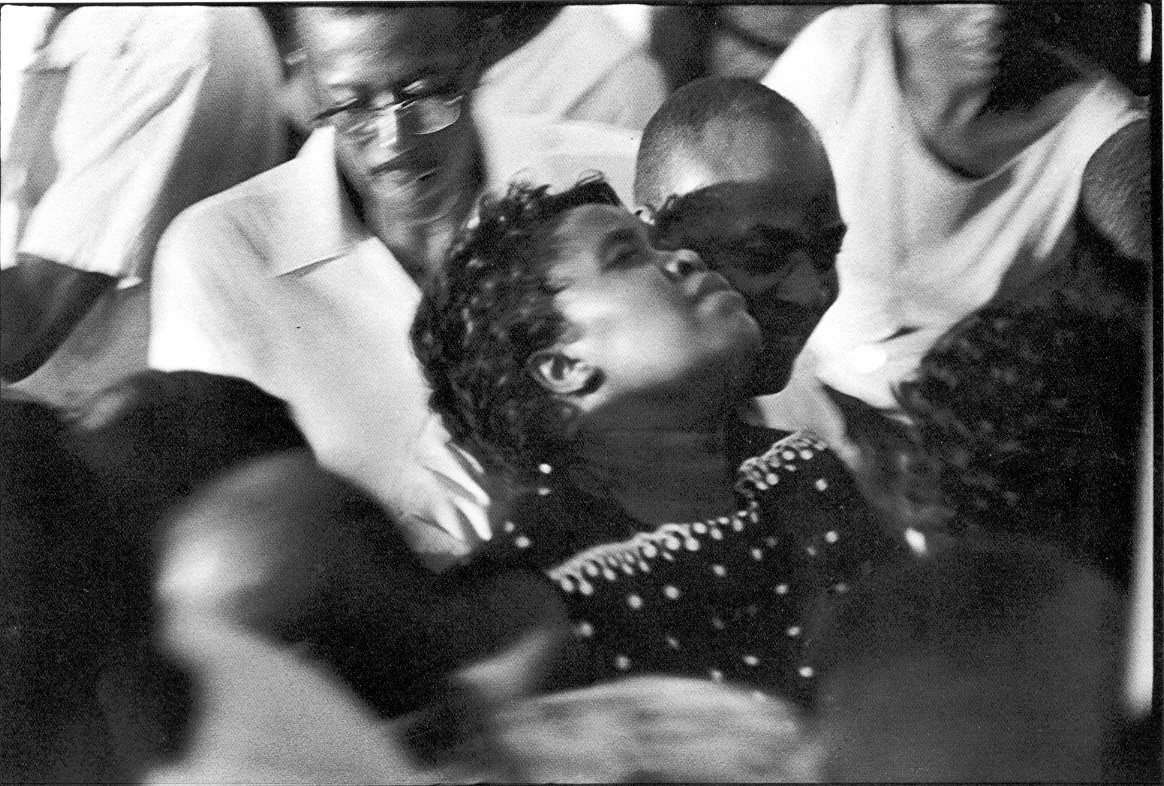

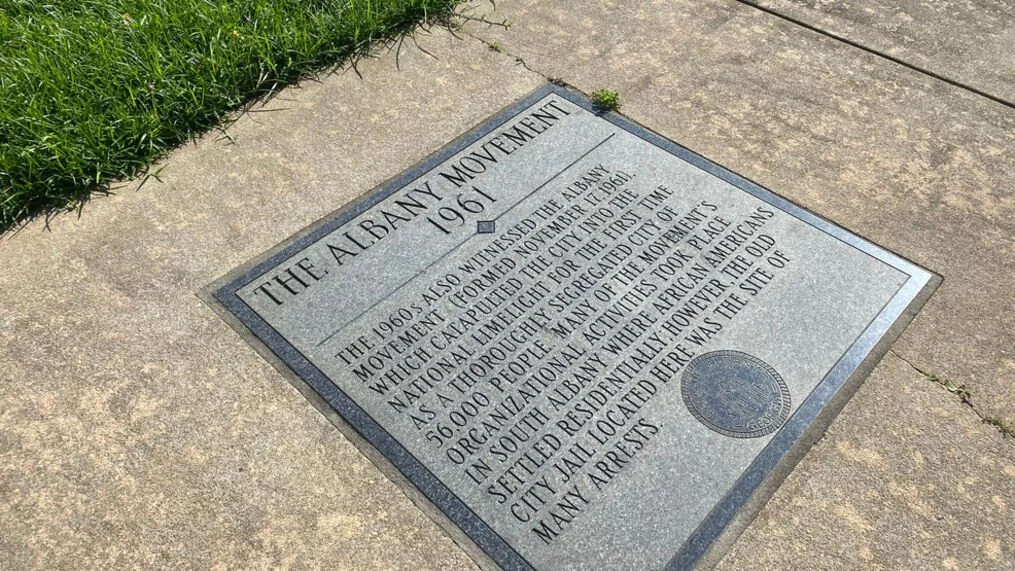

ALBANY, GA, NOVEMBER 1961 — Home from work, home from school, home from jail, dozens dragged themselves to the meeting that night. Martin Luther King was not ready to dream with them — yet. The dream came in song.

Nineteen-year-old Bernice Johnson stepped before the crowd in the Union Baptist Church. She began to sing:

Over my head, I see trouble in the air

Johnson immediately sensed trouble. Tired and terrified, few felt like singing. “Trouble” was hardly the right word for what blacks in Albany faced. “So instead I put in ‘freedom’. . .”

Over my head, I see freedom in the air

“. . . and by the second line everyone was singing.”

Song did not spark the Civil Rights movement at first. There wasn’t much singing in Montgomery, 1955, nor in the first sit-ins. But from the Albany movement onward, every meeting, every march broke into song.

The songs were as feathered as lullabies, as strident as marches. The songs made hair stand on end, made souls sink in sorrow and rise again in triumph. And leading, living those songs was Bernice Johnson Reagon.

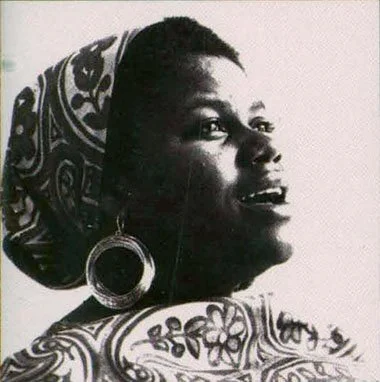

To call her a singer is to call Shakespeare a writer. At 81, Bernice Johnson Reagon is a living testimony to the power of music. Along with numerous awards and degrees, she has been a recording artist, Smithsonian consultant, history professor, and founder of the long-running group “Sweet Honey in the Rock.” And to think it all started with a song.

Black folk in Dougherty County, Georgia were too poor to have a piano in church, so Bernice made her voice an instrument to be reckoned with. From age three, when she entered school, throughout a childhood of singing in her father’s church, the music stirred her.

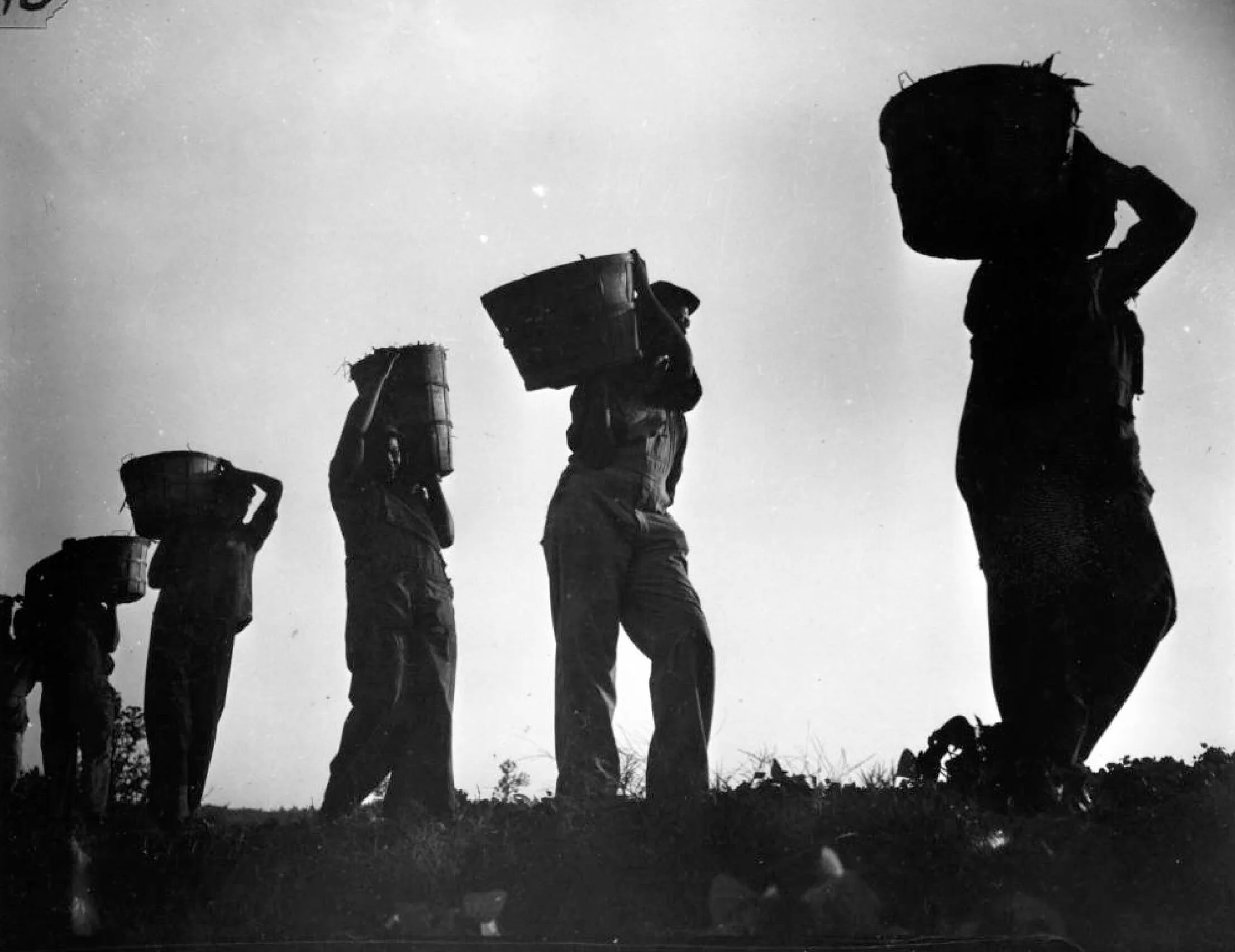

“My history was wrapped carefully for me by my fore-parents in the songs of the church, the work fields, and the blues."

Johnson entered Albany State in 1959, just in time for the “good trouble.” Segregated and bone poor, Albany was stirring. Johnson joined the NAACP but its legal approach wasn’t working. Then SNCC came to town.

In October, 1961, field organizers for the upstart Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee began organizing in Albany. Johnson told Charles Sherrod to change his group’s name. “The term nonviolent did not name anything in my experience.”

But watching Johnson lead Union Baptist in song, SNCC staffers were impressed. James Forman later told Johnson, “I remember seeing you lift your beautiful black head, stand squarely on your feet, your lips trembling as the melodious words 'Over my head, I see freedom in the air' came forth with an urgency and a pain that brought out a sense of intense renewal and commitment of liberation.”

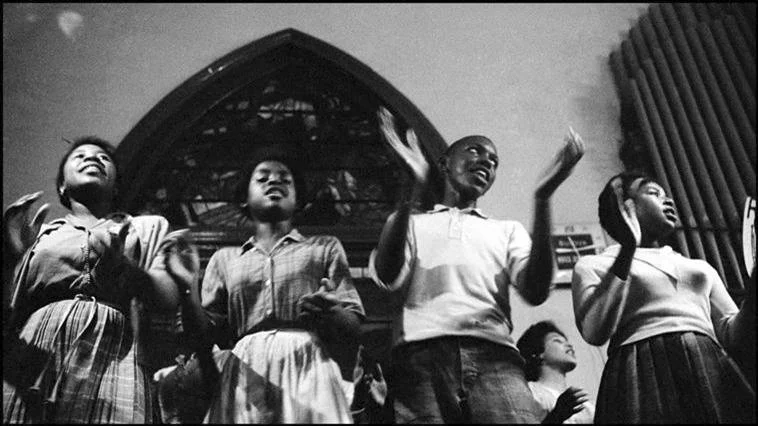

SNCC’er Cordell Reagon was also impressed. In 1962, when he formed the SNCC Singers, he hired Bernice Johnson, by then Bernice Johnson Reagon, to sing alto. Adding a bass and a soprano, the SNCC Singers hit the road.

“We traveled all over the country in a compact Buick,” Rutha Mae Harris recalled. “On one tour, we managed to go fifty thousand miles in nine months without any flights.” The SNCC Singers held forth on campuses, in churches, in coffee houses. At Carnegie Hall, they sang with Harry Belafonte. They raised money for SNCC’s activism, including “Freedom Summer,” but they also raised awareness.

Beyond “Freedom Songs,” the SNCC Singers shared the latest from the front lines of the movement. As “a singing newspaper,” Bernice recalled, their songs “became a major way of making people who were not on the scene feel the intensity of what was happening in the South.”

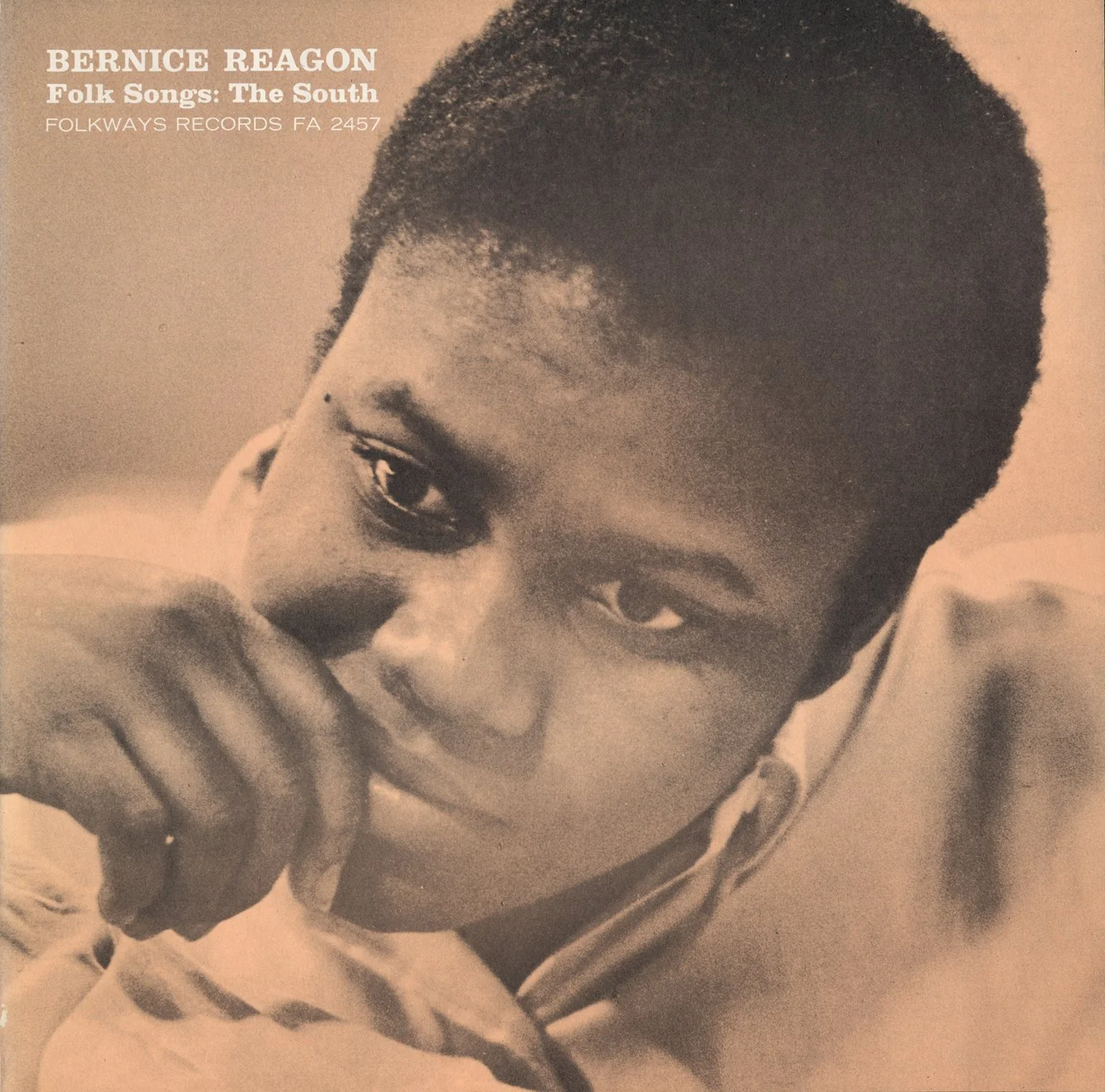

By 1965, with the movement changing, Bernice Johnson Reagon had a daughter, Toshi, a debut album, and a desire to return to college. She graduated from Spelman, then went on to Howard University to earn a doctorate. While at Howard, she gathered fellow “song talkers” to form an a capella group.

She chose the group’s name from Psalm 81:16. “He should have fed them also with the finest of the wheat: and with honey out of the rock should I have satisfied thee.” “Sweet Honey in the Rock” was as soulful as a Freedom Song, as spirited as a freedom march. The group began touring in 1974. They have never stopped.

Through 20 different singers and 27 albums, “Sweet Honey in the Rock” marches on. In 2021, a critic compared them to the Grateful Dead — “their fans arrive in droves whenever and wherever they show up to perform because it’s always a can’t-miss event.”

They have sung at the White House and in major concert halls around the world. Nominated for several Grammies, they have done children’s songs on “Sesame Street” and belted out “sorrow songs” on Ken Burns’ “Civil War.” Dr. Reagon left the group in 2003 but continues to spread the gospel of black history.

After twenty years with the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, Reagon taught history at American University in Washington, D.C. She now accompanies her daughter, Toshi, in concert. And she continues to believe in song, in hope, in freedom.

“In our culture, anything you do disappears the minute you stop doing it. And freedom is like that. People think you are born into freedom. The only freedom you have is the freedom you are exercising. And sitting down thinking it’s going to be there when you need it is going to give you a big surprise.”