MUSIC'S MASTER TEACHER

MANHATTAN — 1958 — The music of the late Fifties was adolescence with a backbeat. Teenagers powered the hit parade. “Jailhouse Rock.” “At the Hop.” “Wake Up, Little Susie. . .”

Then on a frigid Saturday afternoon, while TV pumped out cartoons and westerns, CBS showed young people streaming into Carnegie Hall. Moments later, a conductor in a dark suit stepped onstage. He raised a baton, and a trumpet announced “The William Tell Overture.”

But before you could shout “Hi-yo Silver!” the conductor slashed his baton. The music stopped. He turned to the audience.

“Okay, now, what do you think that music is all about? Can you tell me?”

The audience erupted. “The Lone Ranger!”

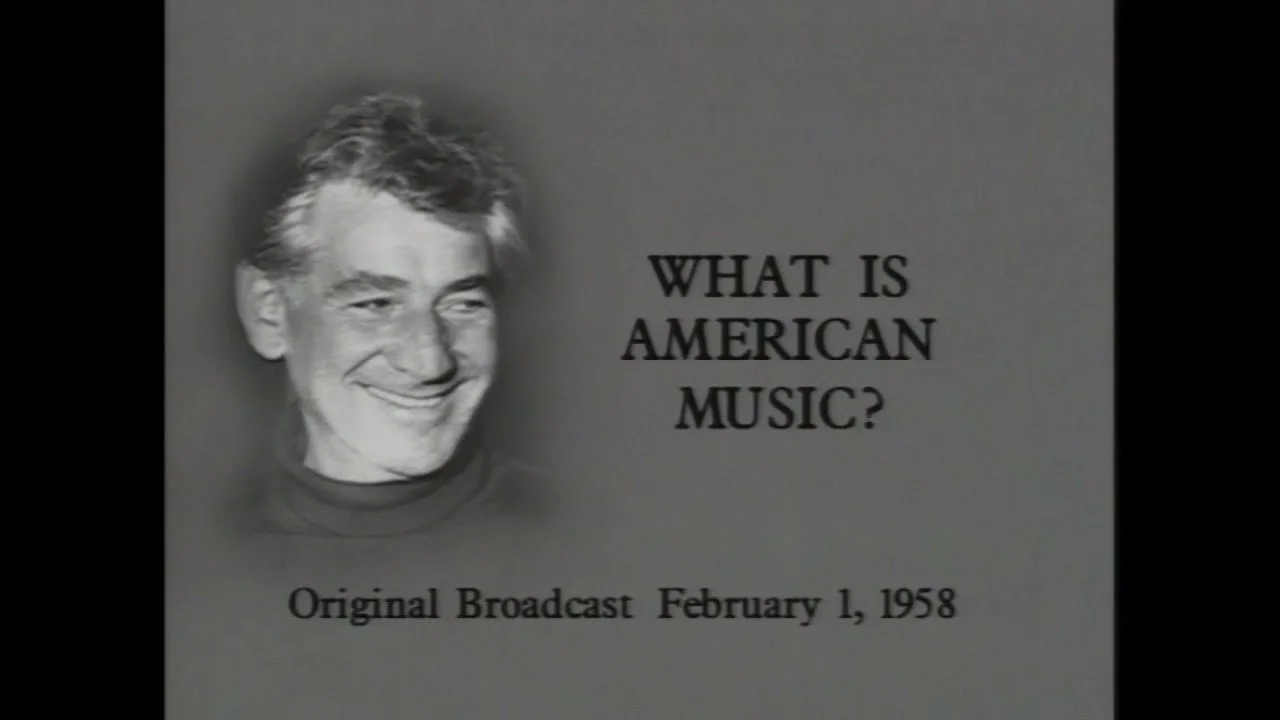

“That’s just what I thought you’d say,” Leonard Bernstein replied. “Cowboys, bandits, horses, the Wild West. . . Well, I hate to disappoint you, but it really isn’t about the Lone Ranger at all.”

Every child of the Cold War knew a harsh truth about music. Along with Elvis and Buddy Holly, some music was (ugh!) classical. Teachers dragged in radios to force-feed this music students. Parents actually listened. Names flew. Beethoven. Bach. Brahms. But no one explained what this music was about or how it worked.

The New York Philharmonic began “Children’s Concerts” in 1925. The series went on tour, nationally, internationally. But Leonard Bernstein brought the concerts to TV. And he brought himself.

Growing up near Boston, entranced by music, “Lenny” became a rising star in the classical world. Piano lessons at ten. First composition a year later. First performance at 14. Then Harvard, grad studies in conducting, and at 25 he became assistant conductor at the New York Philharmonic. But Bernstein had an avocation — teacher.

“Teaching is probably the noblest profession in the world,” he told his young audience, “the most unselfish, difficult, and honorable profession. It is also the most unappreciated, underrated, underpaid, and under-praised profession.”

Before taking over the philharmonic in 1958, Bernstein taught college classes, Tanglewood students, and his own children. But could a teacher make classical music interesting, even fun?

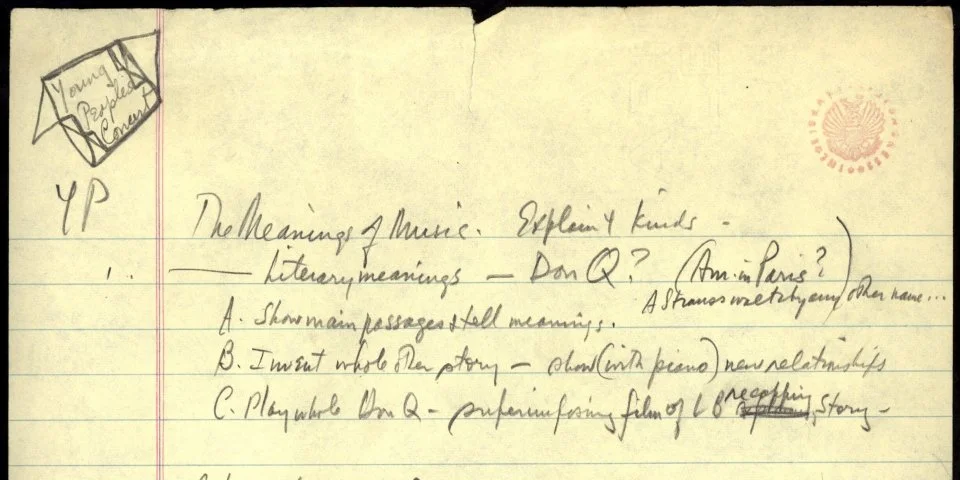

From his debut concert, “What is Music About?” Bernstein displayed his virtuosity as conductor, pianist, teacher. First ingredient — curiosity.

“No matter what stories people tell you about what music means, forget them. Stories are not what music means. Music is not about things. Music just is. It’s a lot of beautiful notes and sounds put together so well that we get pleasure out of hearing them. So when we ask ‘what does it mean? What does this piece of music mean’ we are asking a hard question. That’s the question we’re going to try to answer today.”

Over the next 14 years, Bernstein led 53 young people’s concerts. The series moved from Carnegie Hall to Lincoln Center, from black and white to color. Bernstein’s second ingredient — surprise — kept young people guessing what they’d hear next.

To explain music’s Dorian mode, Bernstein played the Beatles’ “And I Love Her.” The Mixolydian mode brought The Kinks’ “You Really Got Me.” He played “La Bamba,” sang “Volare,” banged out boogie-woogie. He treated kids with respect, as “young people” with minds, not just tapping feet.

“No subject is too difficult to talk to the kids about. You just have to know where the pain is.”

Like the best teachers, Bernstein asked questions, played off kids’ answers, cut from idea to example. Parents who hoped their kids would get a crash course in “highbrow music” got much more.

“An electric current of subversiveness ran through these concerts,” a biographer wrote. “Bernstein seemed almost to reach inside the psyches of his listeners and unlock the barriers between them and music.”

Swirling his arms, entranced by music and ideas, Bernstein seemed to be conducting his audience as much as an orchestra. Critical of “the music appreciation racket” that dumbed down classical music, Bernstein openly tackled terminology — orchestration, concerto, counterpoint. “Don’t you ever be scared of counterpoint,” he told kids. “It’s not the absence of melody. It’s an abundance of melody.”

And on the series went, expanding, deepening, astounding. “Who is Gustav Mahler?” “Unusual Musical Instruments.” “What is a Concerto?” Concerts paid tribute to musical styles — latin, jazz, folk — and to composers — “Forever Beethoven,” Bach, Berlioz, Strauss. . .

Even while on sabbatical, Bernstein continued his youth concerts. They were, he later said, “among my favorite, most highly prized activities of my life." Bernstein left full-time conducting in 1969 but continued the concerts for three more years.

No one knows how many young people owe their musical interests to Leonard Bernstein. “The series would be lost without him,” the New York Times wrote, “for in this area of pedagogical showmanship he has no real competitor.”

The series continues to this day, without television, without “Lenny,” who died in 1990. All 53 Bernstein concerts are available on DVD. Most are on Youtube.

TV and fashions have aged since the Sixties. There — in black and white — is the philharmonic, all men, all pasty-faced. And there is Bernstein, sometimes using dated terms — Indian and Negro. But his love of teaching and his joy in music resonate like bass notes on a cello.

Bernstein at the piano. A Chopin nocturne. “Beautiful, isn’t it? But what’s it about? Nothing.” He leads the orchestra in a Beethoven sonata — “It’s not about anything.” He moves on to Ravel and the Blue Danube Waltz. . .

“Now we can really understand what the meaning of music is. It’s the way it makes you feel when you hear it. . . We don’t have to know a lot about sharps and flats and chords and all that business in order to understand music. If it tells us something, not a story or a picture but a feeling, if it makes us change inside — to have all of these good feelings that music can make you have — then you’re understanding it.”