DEEP, DEEP DOWN. . .

BERMUDA, 1930 — Ever since the first sailor set out on the first sea, the world beneath the waves had been a mystery. Even in oceans mapped around the globe, no one knew what lived, swam, or slithered more than 200 feet below.

Jules Verne imagined monsters “20,000 leagues under the sea.” “The ocean,” wrote Edmund Burke, “is the object of no small terror.”

And then. . .

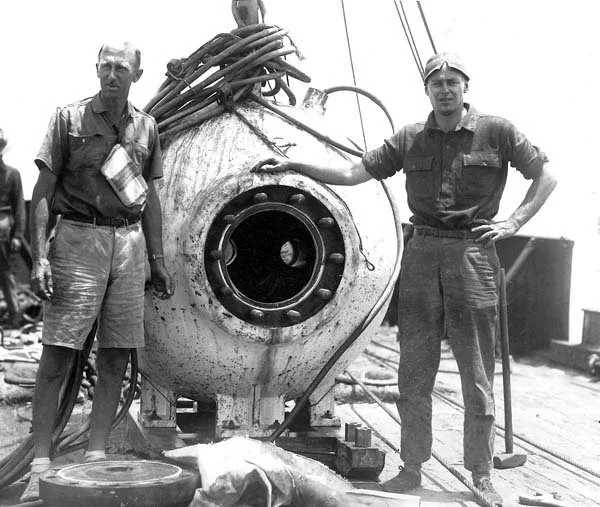

On board the HMS Ready, two American explorers prepare to go deep. Deeper than the deepest helmet diver, they will descend a thousand, two thousand feet down, down. . . . The men are your typical explorer types — rugged, “dashing,” a little crazy, perhaps. But more curious is the craft that will take them on a “round trip to Davy Jones Locker.”

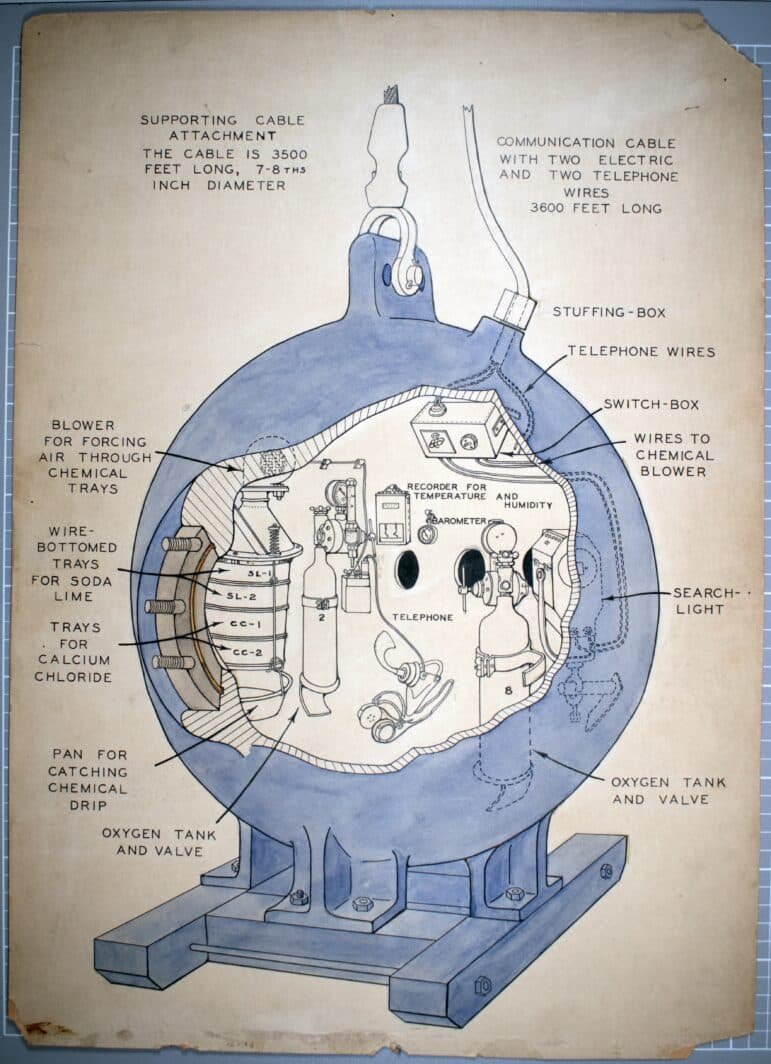

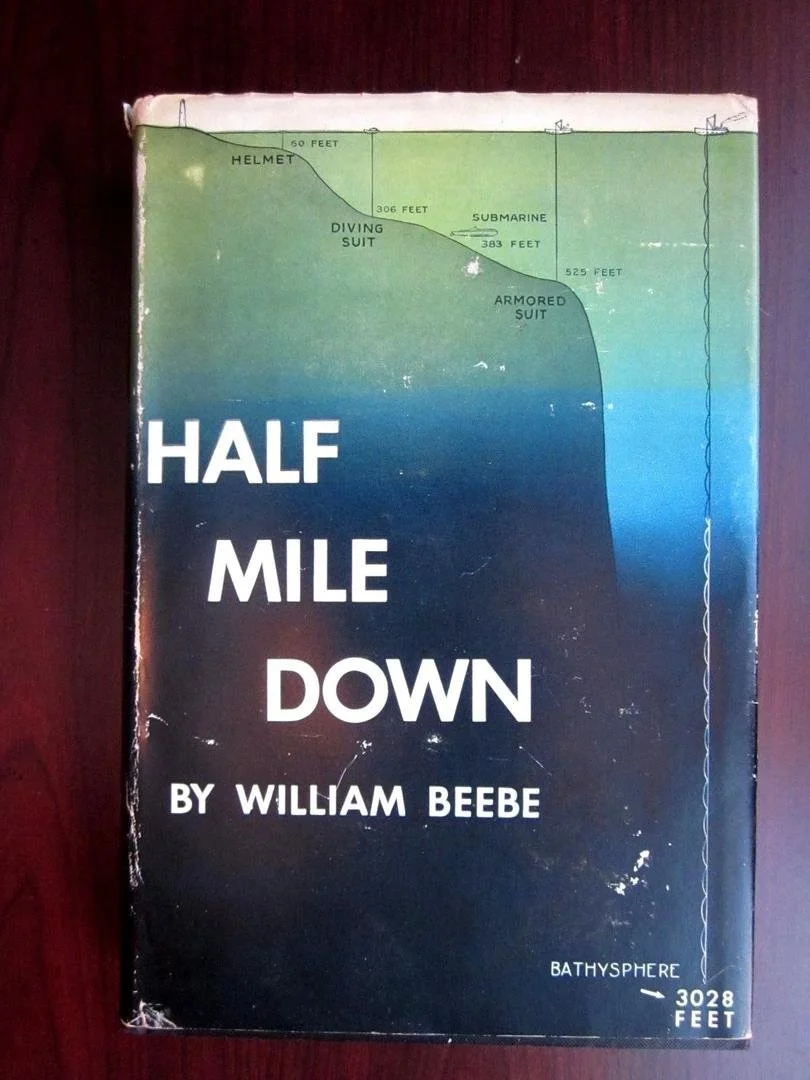

The Bathysphere seems simple. A steel cylinder with windows. Yet to withstand pressure topping a thousand pounds per square inch, the steel is an inch thick, the quartz windows three inches. The Bathysphere weighs 5,000 pounds, yet two men must cram into a space less than five feet across.

Wedged behind the 400 pound door, hoisted by a steel cable, the explorers splash into the sea and sink, sink. By phone cable, they describe what they see.

100 feet — All red light is gone. Jellyfish glow.

200 feet — pilot fish, pure white with jet black bands.

500 feet, 600, 700. . .

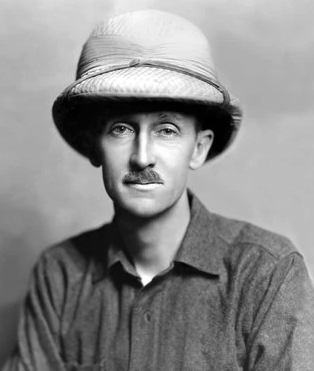

By 1930, the pilot, William Beebe, was a household name. A naturalist’s Indiana Jones, Beebe dropped out of college to work at a zoo, then set out on expeditions. Borneo. Java. The Himalayas. . .

Collecting specimens, writing science papers and best-selling books, Beebe hobnobbed with Theodore Roosevelt and dined with famous authors. He loved costume parties, played the banjo, and clung to his teenage dream — “to be a Naturalist is better than to be a King."

By 1926, Beebe had explored much of the globe — on its surface. Then honeymooning in Bermuda, he befriended a British prince. Prince George gave Beebe his own outpost on Nonsuch Island, and the naturalist fell in love with the sea.

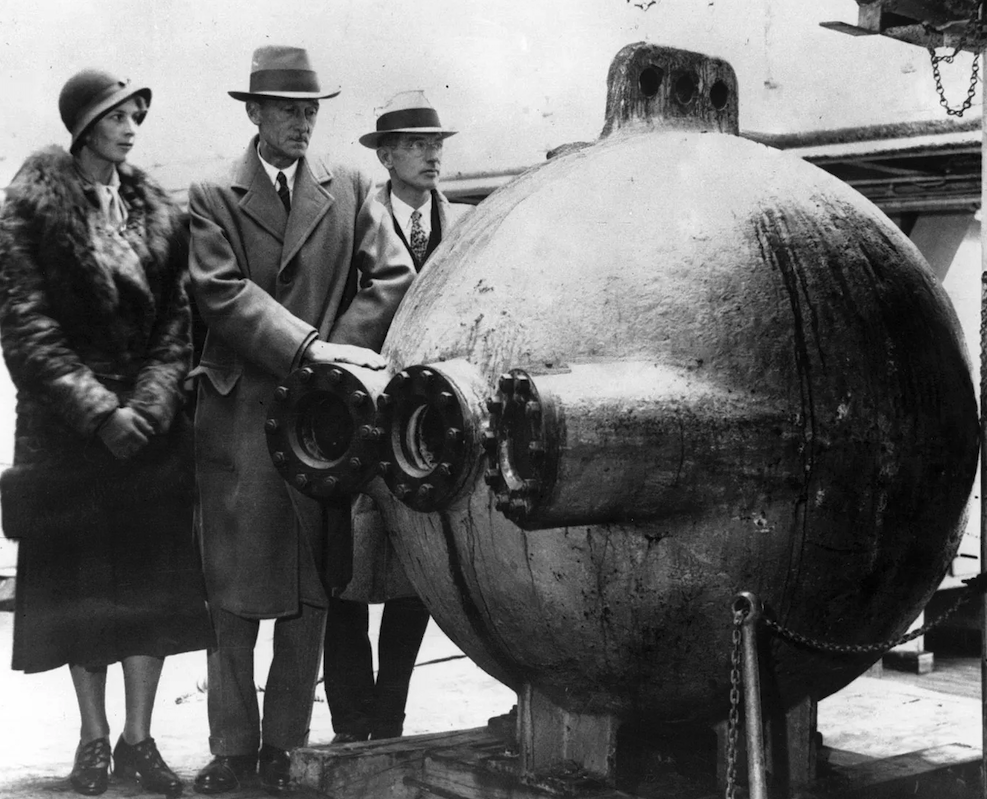

Donning a helmeted suit, Beebe dove to five hundred feet. He cataloged hundreds of species never seen before, but he yearned to go deeper. A cylindrical tank might work, but engineer Otis Barton, reading Beebe’s plan in the New York Times, knew that only a sphere could withstand deep sea pressures. When the two were introduced in 1928, the Bathysphere was born. Beebe funded it, Barton designed it. Together, they would test it.

Oxygen came from high-pressure cylinders onboard. Carbon dioxide from the men’s breath was neutralized by pans of calcium chloride. A light outside lit up an undersea world “black as hell.” But the biggest challenge was space. “The longer we were in it,” Beebe said, “the smaller it seemed to get.”

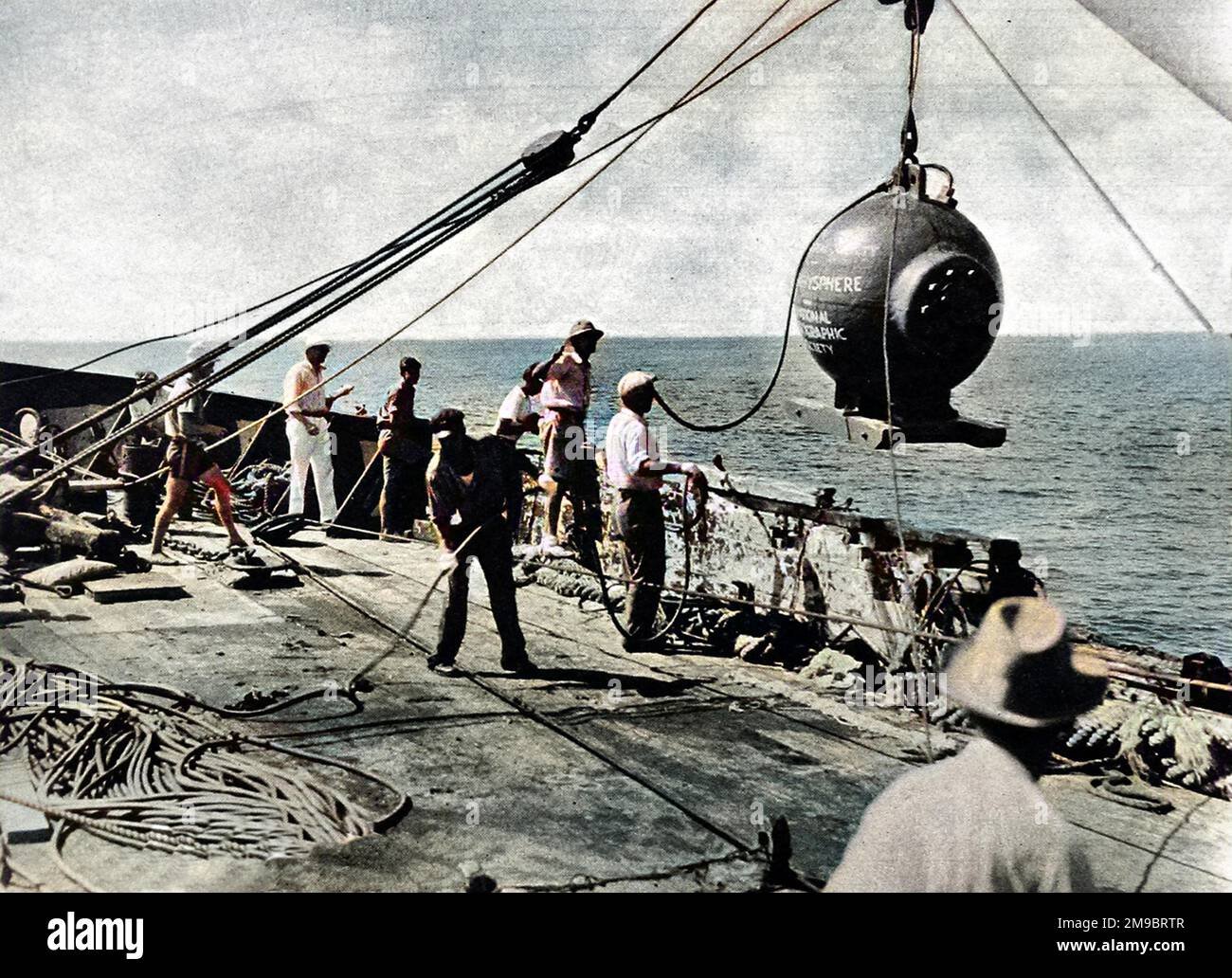

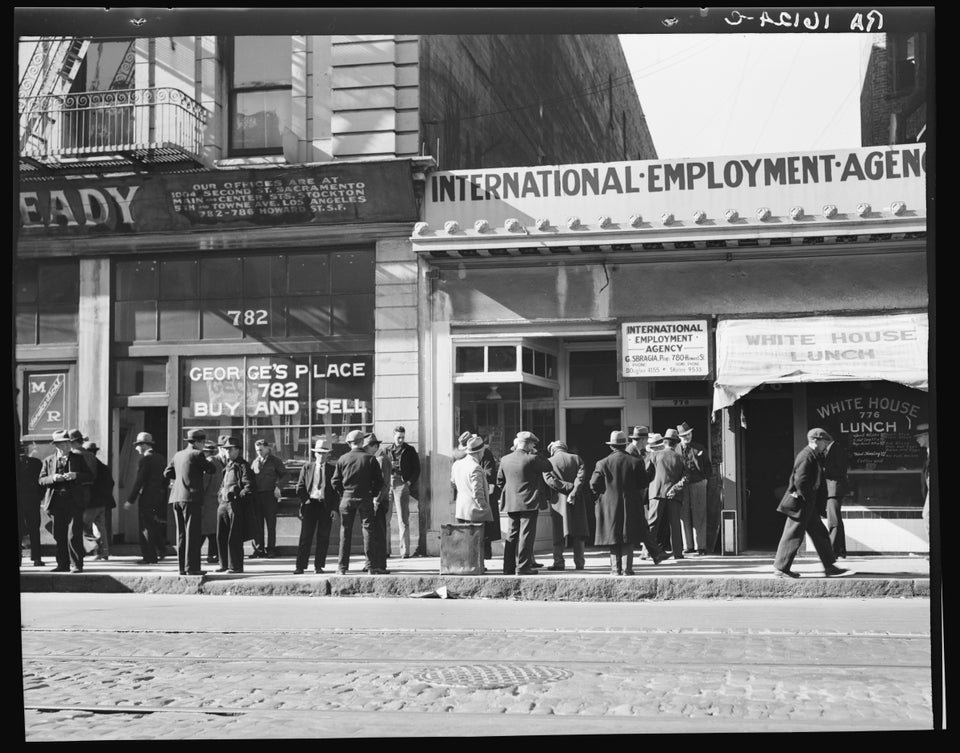

That first dive in 1930 took them deeper than anyone had ever gone. 803 feet. But problems arose, including leaks, tangled hoses, and Depression-era funding. Beebe got National Geographic on board, then went on the air — from beneath the sea.

In September, 1932, while America teemed with soup lines, bread lines, and 25 percent unemployment, millions tuned to NBC radio for a broadcast from another world. From 1,500 feet down — and sinking — Beebe told listeners across America and Europe what he saw through his windows.

“Below humanly visible light,” the Bathysphere’s lamp turned the depths a “pale green to pale blue. . . cold and clammy.” Soon Beebe reported “schools of fish, all brilliantly lighted.”

At 2,200 feet, he saw “some creature, several feet long, dart toward the window, turn sideways and -- explode.” The flash lit up Beebe’s face and the inner window sill. “I saw the great red shrimp and the outpouring fluid of flame."

Then the Bathysphere began to rock and shake. Beebe hoped to descend a half-mile but had to pull up short. Bloodied and battered, he and Barton were hauled to the surface. It is hard to imagine how sweet the air, how beautiful the sky.

For the next two years, the Bathysphere went deeper. Beyond a half-mile, Beebe and Barton saw fanged eel-like creatures, lights like fireflies, slithering squid, and phosphorescent jellyfish.

They also set depth records, bottoming out at 3,028 feet. But Beebe, as much naturalist as adventurer, valued discovery more than records. And though drawn deeper, he remained chilled by the ocean’s depths.

“These descents of mine beneath the sea seemed to partake of a real cosmic character," he wrote in his best-selling Half a Mile-Down. "First of all there was the complete and utter loneliness and isolation, a feeling wholly unlike the isolation felt when removed from fellow men by mere distance. . . It was a loneliness more akin to a first venture upon the moon or Venus."

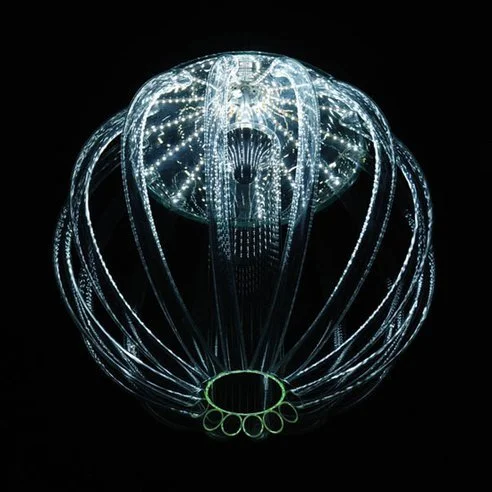

After 65 dives, Beebe returned to exploring in sunlight. Focusing on the tropics, he gathered specimens from throughout Central and South America. By the time he died in 1962, Jacques Cousteau had invented SCUBA gear and a new Bathyscaphe (above) was descending into the ocean’s deepest trenches. William Beebe was largely forgotten.

But Rachel Carson, who dedicated The Sea Around Us to Beebe, remembered. E.O. Wilson cited him as a hero. And Beebe left 800 articles, 21 books, and some five dozen species named after him. The boy turned naturalist-king also left a legacy of wonder.

“Boredom is immoral,” he wrote. “All a man has to do is see. All about us, nature puts on the most thrilling adventure stories ever created, but we have to use our eyes.”