THE UNIVERSE TURNS 100

PASADENA, CA — OCTOBER 4, 1923 — On a brisk fall night, with the lights of Southern California twinkling below, a robust middle-aged man, dressed in knickers and a beret, jogs up a hill to check on the night sky.

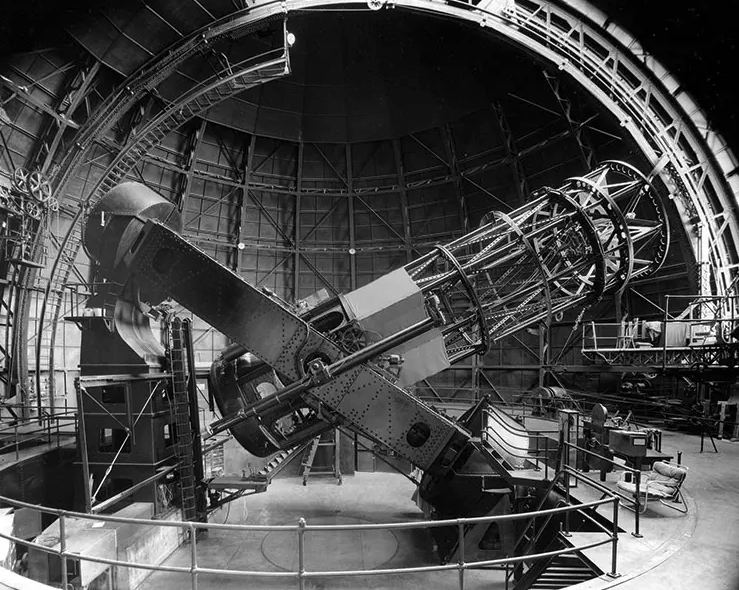

With a great groan and rumble, the steel dome of Mount Wilson’s 100-inch telescope opens to the heavens. The astronomer sits, dwarfed by this 75-ton eye on the skies. He slides a photographic plate into a slot, sets his watch for a 40-minute exposure, and lights his pipe. Another night at the universe has begun. But this is not just another night.

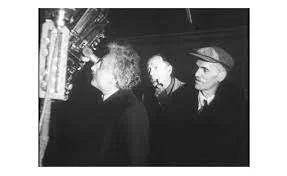

A century ago, the results of that October sighting blew away every conception — ancient or modern — of the universe. And with one discovery, Edwin Hubble joined the ranks of Copernicus and Galileo. But this Midwestern farm boy was not finished. Soon he would make his most startling discovery — that our universe is expanding.

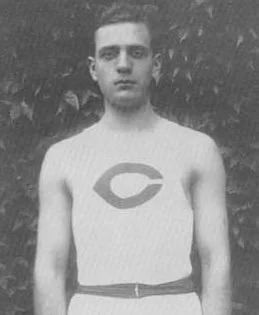

“Edwin Hubble,” his high school teacher predicted, “will be one of the most briliant men of his generation.” Yet Hubble preferred sports to study. At the University of Chicago, where he led the basketball team to a national championship, he dabbled in math and astronomy but promised his father, an insurance salesman, that he would not make science a career. At Oxford, as a Rhodes Scholar and champion high-jumper, he studied law. Back in the US, he set up a practice.

Then in 1913, when his father died, Hubble heard the universe beckon. “Astronomy is something like the ministry,” he later said. “No one should go into it without a call.”

Ever since ancient astronomers first charted the night sky, those who heard the call had crafted a cornucopia of cosmologies. The universe, some said, was the handiwork of God, or gods, but always finite, always bounded by what we could see, by the light that our feeble eyes and tiny telescopes could gather.

By the 20th century, the universe was known to be immense, but our conception of the cosmos stopped at the edge of our own galaxy, the Milky Way. A few faint lights seemed farther away, but no one could explain these “island universes,” and no one could measure their distance. So no one was sure. Wasn’t the Milky Way all there was?

On that October night in 1923, Hubble was studying the stars known as Cepheid variables. Their regular pulses allowed for precise measurement of their distance. And when Hubble aimed Mount Wilson’s enormous eye at the cluster called M31, he calculated the data that broke it all open. M31 was hundreds of times more distant than the edge of the Milky Way. It had to be another galaxy, beyond our own. It would soon be called Andromeda.

When Hubble sent the news to a Harvard astronomer, long skeptical of “island universes,” the shock was Einsteinian. “Here is the letter that has destroyed my universe,” Harlow Shapley said.

On New Year’s Day in 1925, the American Association for the Advancement of Science hailed Hubble’s discovery. “It opens up depths of space previously inaccessible to investigation. . . and expands one hundred fold the known volume of the material universe.”

There would be many more nights at the universe. Throughout the 1920s, as the rest of America whooped it up, Edwin Hubble jogged up the hill to check on the night sky. Now knowing that each distant, blazing cluster was another galaxy, he began measuring “red shift,” the stretching of light waves due to each galaxy’s rushing away from us. He soon saw a pattern.

The farther away a galaxy, the faster it was moving. It was as if, at some starter gun, a hundred cyclists sprinted off. Clearly, the cyclists in the lead are going faster. And so are the galaxies. Hubble soon calculated a ratio between speed and distance — “Hubble’s constant.” The ratio became a symbol — H. (Sorry, have to use an equation.)

V=Hd — Velocity equals distance times a fixed number.

A simple equation, but one that, astronomer Allan Sandage wrote, “has that exquisite beauty that is essential for truth.”

“The history of astronomy,” Hubble wrote, “is a history of receding horizons.” And with his discoveries, astronomers began to expand the horizons of the universe, culminating in a cosmology called the Big Bang.

Hubble worked at Mount Wilson for the rest of his life, eventually pioneering work with a nearby 200-inch telescope, then the world’s largest. When he died in 1953, friends recalled the afternoon when shared the photographic plates that proved the expansion.

“How terrifying!” one friend said.

“Only at first,” Hubble replied. “When you are not used to them. Afterwards, they give one comfort. For then you know that there is nothing to worry about — nothing at all.”

In 1990, astronomy’s horizons got their biggest boost when the first telescope was launched into orbit. They called it, of course, the Hubble.

The Hubble Space Telescope gathered light from 13.7 billion light years away. Might that unfathomable number mark the edge of the cosmos? Stay tuned.

“The search will continue,” Edwin Hubble wrote. “The urge is older than history. It is not satisfied and it will not be oppressed.”