THE POET AND HER WILD GEESE

SUBURBAN CLEVELAND, 1940S — A young girl, far too young, runs from her house into the woods. There she begins making huts out of sticks and fashioning dream worlds brighter than her own. On her next visit, she brings pencil and paper.

Tell me, what else should I have done?

Doesn't everything die at last, and too soon?

Tell me, what is it you plan to do

with your one wild and precious life?

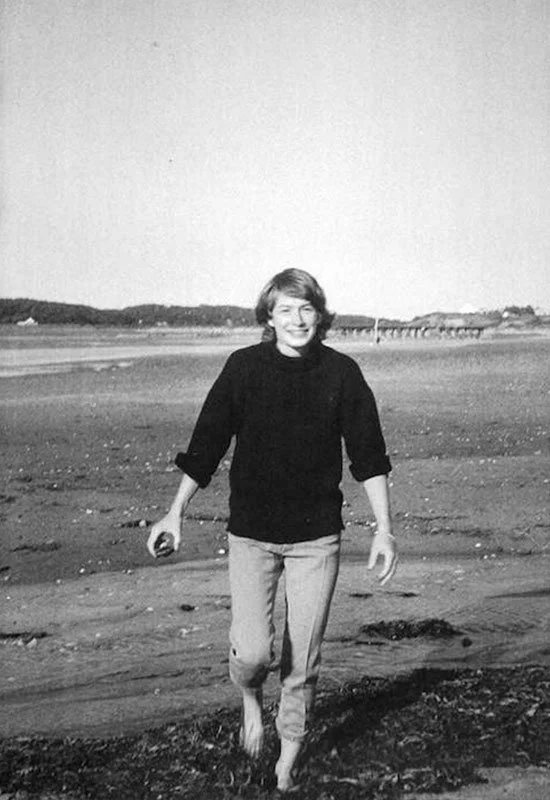

Through one wild and precious life, Mary Oliver walked, notebook in hand. Along the beaches and through the woods of Cape Cod, Oliver gathered hope and redemption. The many who loved her poetry thought it came from light itself, but it was born in darkness. She was the light.

“Mary Oliver's poetry is an excellent antidote for the excesses of civilization,” the Harvard Review wrote. “She is a poet of wisdom and generosity whose vision allows us to look intimately at a world not of our making.”

Intensely private, Oliver rarely spoke about her childhood. In 2011, when she told an interviewer of “a very dark and broken house that I came from,” even devout readers were surprised. Among her 33 collections of poems, only one — Dream Worlds — mentioned the darkness.

RAGE

You are the dark song

of the morning;

serious and slow,

you shave, you dress,

you descend the stairs. . .

But you were also the red song

in the night,

stumbling through the house

to the child’s bed,

to the damp rose of her body. . .

“I couldn’t handle that material,” Oliver said, “except in the three or four poems that I’ve done; just couldn’t.” Turning away, running away, Oliver left home on the day after high school graduation. She drove straight to Steepletop, the New York home of her favorite poet, Edna St. Vincent Millay.

“Vincent” had passed on but her sister, Norma, still lived there. She and Oliver became friends and Oliver stayed for six years, helping catalog Millay’s papers. Meanwhile, she wrote poems, publishing her first collection in 1963. It made as little noise as most poetry makes, but Oliver had found more than one muse at Steepletop.

One day, a Village Voice photographer showed up. “I took one look and fell hook and tumble,” Oliver wrote. By then, Oliver had her own apartment in The Village. Back in the city, she began seeing Molly Malone Cook. In 1964, they visited Provincetown, Massachusetts at the tip of the tip of Cape Cod.

“I too fell in love with the town, that marvelous convergence of land and water; Mediterranean light; fishermen who made their living by hard and difficult work from frighteningly small boats; and, both residents and sometime visitors, the many artists and writers. M. and I decided to stay.”

Oliver and Cook melted into P’town, as locals call it. Cook ran a photo gallery and a book shop. Oliver, like Thoreau at Walden Pond, “traveled a good deal” without ever leaving. “People say to me: wouldn’t you like to see Yosemite? The Bay of Fundy? The Brooks Range? I smile and answer, ‘Oh yes—sometime,’ and go off to my woods, my ponds, my sun-filled harbor, no more than a blue comma on the map of the world but, to me, the emblem of everything.”

And gradually, readers came to her. She published just five more collections in 20 years, but in 1984, American Primitive won the Pulitzer. Several years later, New and Selected Poems won the National Book Award. And poems like “Wild Geese” won the heart of anyone who needed solace and a friend.

Oliver’s work, Poetry wrote, has “an uncomplicated, nineteenth-century feeling.” yet 21st century readers began posting it everywhere. On Instagram, on Pinterest, on refrigerators, notebooks, and deep inside private souls. Some critics scoffed.

“Her verse is easy to digest, smooth and slightly sweet like pap,” Poetry wrote. Yet transcending “nature poems,” the critic added, “her poems aren’t snapshots of nature. She observes conscious life, even beacons it.”

Oliver accepted her fame, but wanted to be left alone. She gave up teaching, gave few interviews, few readings. Her childhood aversion to “the enclosure of buildings” kept her out walking, pen in hand. Once she tried to kick the habit, leaving her pen at home, but she was soon hiding pencils in the trees, just in case.

As she aged and suffered the loss of her lifelong companion, Oliver’s poems began to morph into prayers. Many, the New Yorker wrote, “would not feel out of place in a religious service, albeit a rather unconventional one.” Yet her words soothed a growing congregation. The poetry which saved Oliver as a child performed the miracle again and again.

“Poems are not words, after all, but fires for the cold, ropes let down to the lost, something as necessary as bread in the pockets of the hungry. Yes, indeed.”

Oliver survived lung cancer in 2012. By then, she had moved to Florida where she was “trying very hard to love the mangroves.” She succumbed to lymphoma in 2019. She had seen the end from a long way off.

When death comes

like the hungry bear in autumn;

when death comes and takes all the bright coins from his purse. . .

When it's over, I want to say all my life

I was a bride married to amazement.

I was the bridegroom, taking the world into my arms.