THE NEWS: A USER'S MANUAL

If we read of one man robbed, or murdered, or killed by accident, or one house burned or one vessel wrecked. . . we need never read of another. — Thoreau

It’s easy to say that the news, like Wordsworth’s world, is “too much with us now.” We all know that, and some of us have begun to pull back. To cancel subscriptions, plan news-free days, turn off the 24/7. (And subscribe to The Attic?)

But there are deeper thoughts about why news is the narrative of our times. And because they ask us to think rather than just react, you will never see, hear, or read these thoughts in the news.

Though published a while back, The News: A User’s Manual remains a thoughtful study of our headline-sated world. Author Alain de Botton (How Proust Can Change Your Life) applies his trademark blend of analysis, humor, and wide reading to put news and its junkies on the couch.

Chapter by chapter, this “user’s manual” lays bare the motives and dangers of the news and its component parts. Why do we crave Political News? What does World News tell us and what does it leave out in favor of tragedy and turmoil? Why does news of the economy leave us angry and ignorant? Celebrity, Disaster, Consumption, Culture — de Botton explains the psychological appeal of each.

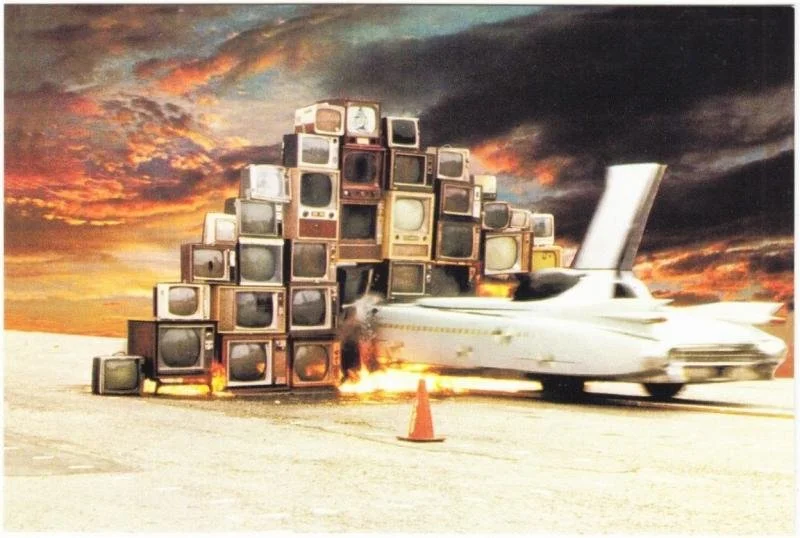

The result makes the “familiar habit” of news “seem a lot weirder and rather more hazardous than it does at present.” And for heavy news consumers, the world seems a lot meaner than it is.

Our modern world, de Botton notes, is “an era contemporaneous with the triumph of news.” Round-the-clock news only dates to the 1980s, and the echo chamber of social media and smart phones is younger still. But de Botton is no Luddite, calling for us to “reject it.” Of course there is good reason to “stay informed.” But as David Byrne’s upbeat website reminds us, the news is not the only window on the world.

As for de Botton, he simply asks us to think about why we crave the news and what this habit is doing to us. An hourly news fix satisfies many primal urges, he writes. The need for diversion. For envy. For safety. For community. But these needs found other fixes before the news triumphed, and de Botton is at his best when he reminds us how the world at large was perceived before the news triumphed.

De Botton tells us how Flaubert, post Madame Bovary, compiled a Dictionary of Received Ideas that captured the banality of the news. To wit:

BUDGET: Never balanced.

EXERCISE: Prevents all illnesses. To be recommended at all times.

Elsewhere, de Botton wonders how much wiser the news would be if written by our best authors, depicted by our best artists. Which leads to his over-arching question — why are we hooked on the news when we could be seeing the world through more inclusive eyes?

“In it scale and ubiquity, the contemporary news machine can crush our capacity for independent thought. . . We need, on occasion, to be able to rise up into space in our imagination. . . to a place where that particular conference and this particular epidemic, that new phone and this shocking wildfire will lose a little of their power to affect us.”

Back when 24/7 news was new, Garrison Keillor lashed out against a Minneapolis newspaper that dissed him in a profile. His response was something I’ve never forgotten. “People who choose to rely on you for information have chosen to lead a smaller life.” The same can be said, de Botton cautions us, of all news.

“A flourishing life requires a capacity to recognize the times when the news no longer has anything original or important to teach us; periods when we should refuse imaginative connection with strangers, when we must leave the business of governing, triumphing, failing, creating or killing to others, in the knowledge that we have our own objectives to honor in the brief time still allotted to us.”