THE OTHER OPPENHEIMER AND HIS PALACE OF WONDER

ALAMAGORDO, NM, JULY 16, 1945 — As the mushroom rises, the “father of the bomb” recalls a Hindu scripture: “Now I am become Death, destroyer of worlds.” But at his side, his brother sees a greater peril — ignorance.

It was “an unearthly hovering cloud,” Frank Oppenheimer recalled. “Very bright and very purple and very awesome.” The cloud, he said, “just seemed to hang there forever.”

The fate of J. Robert Oppenheimer is the stuff of books, movies, and science dethroned. But while one Oppenheimer brother fell, the other rose from the ashes of Alamagordo to create a palace of wonder.

Located on a pier jutting into San Francisco Bay, the Exploratorium is not so much a museum as a portal. Pass through its doors and a universe of thought tantalizes, teases, delights. The Exploratorium, the New York Times wrote, rings “with the happy cacophony of hundreds of 10-year-olds getting their minds blown.” This first American “hands on” science museum, the inspiration for all the rest, is dedicated to discovery, and to the memory of the “other Oppenheimer” whose curiosity it still captures.

Growing up in the shadow of his brilliant older brother, Frank Oppenheimer drove his parents crazy with all his tinkering. “I used to go around the house with an empty milk bottle pouring a little bit of every chemical, every drug, every spice into the bottle to see what would happen,” he recalled. “Of course, nothing happened. I ended up with a sticky grey-brown mess.” Yet Oppenheimer came to see this kind of play as the basis for all research. And occasionally, he noted “something incredibly wonderful happens.”

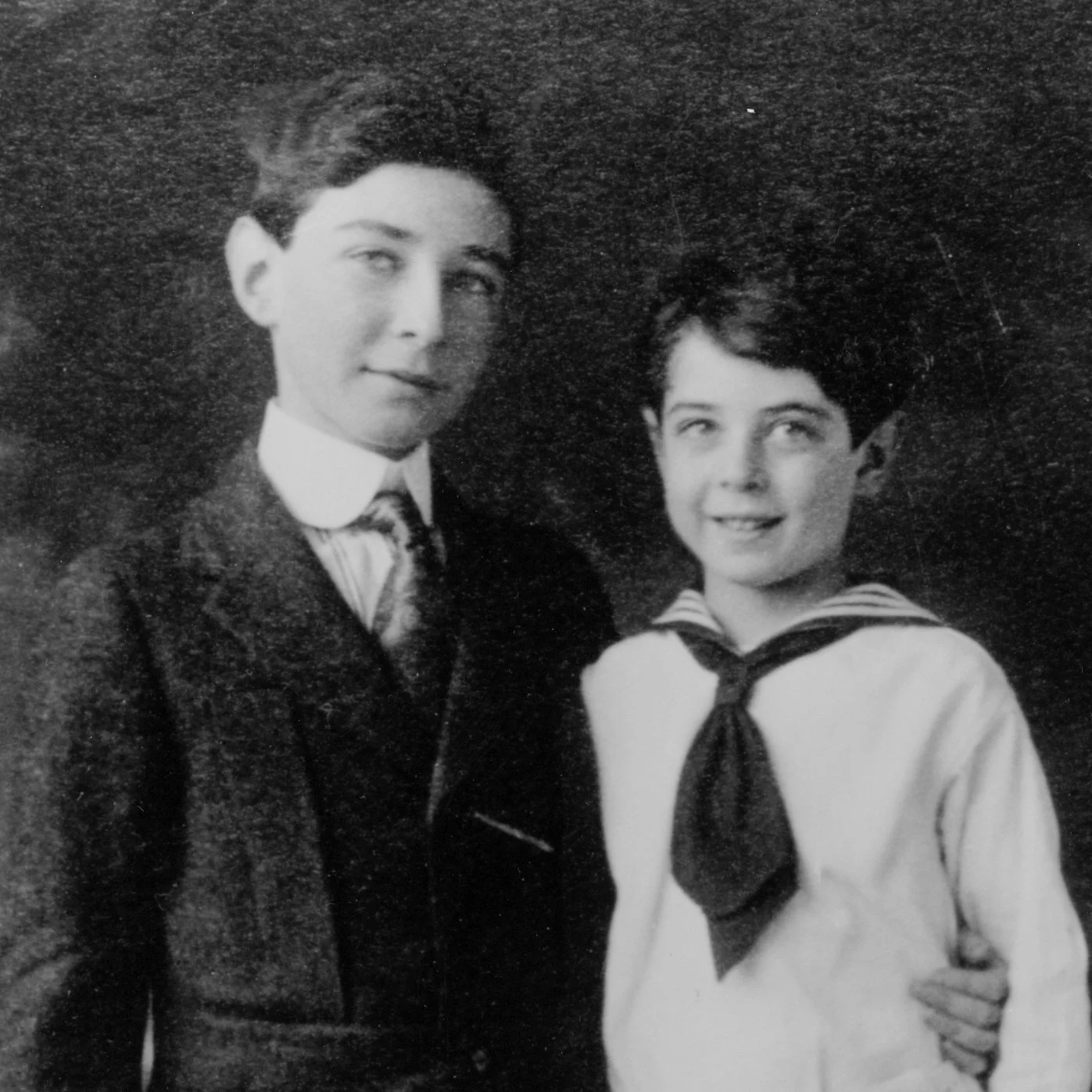

A skilled flautist, Frank considered a career in music, but Robert convinced him that physics would be more fun. The older Oppenheimer, who earned his Ph.D at 23, considered the younger as “slow.” Frank did not getting his doctorate until age 27. But when Robert needed the best minds for the Manhattan Project, he invited Frank.

While Robert and his team worked in New Mexico, Frank supervised the creation of U-235 at Oak Ridge, Tennessee. He only came to New Mexico for the Trinity test. The day after Trinity, feeling like “the uncle” of a terrifying new age, Frank began “speaking all over the map” to warn a giddy public. His past, however, soon caught up with him.

Robert Oppenheimer never joined the Communist Party, but Frank did. In 1947, he was fired from the University of Minnesota, and blacklisted. Unable to find work, he bought a ranch in Colorado and raised cattle. Only when the blacklist was lifted, in the late 1950s, did he get back to teaching — high school.

Appalled by dull textbooks, Frank devised a hundred “hands on” activities. A decade later, after he toured European science museums and got enough grant money, this “library of experiments” jumpstarted the Exploratorium. Housed in an old warehouse, the original Exploratorium “had all the charm of a blimp hangar,” one newspaper wrote. But the Exploratorium did more than teach. “No one flunks a museum,” Frank liked to say.

Just inside the doors a sign overhead read: “Here is Being Created the Exploratorium — a Community Museum Dedicated to Awareness.” And while visitors looked on, engineers tinkered with new exhibits, letting the public, as Frank said, experience “the way a shop smells when you burn the wood in a saw, or smell the oil from a lathe.”

Moving deeper inside, visitors, then and now, simply explore. Drop a coin in a donation box and a lightning bolt rises from a Tesla coil. Tornadoes form in tubes. Light splinters into colors. Inside the dark “Tactile Dome,” one feels instead of sees. A bicycle generator shows how much electricity a single bulb needs. Art installations dazzle with sound and color.

“The whole place seemed to have a heartbeat, a breath, a voice — as if it were whispering to itself,” K.C. Cole wrote in her biography of Oppenheimer. “It was not so much a place as a way of being in the world — a verb rather than a noun: spin, blow, reach, vary, strum, look, throw, fiddle, watch, wonder.”

Curious about something? Momentum, inertia, optics, animal behavior, language, math? The Exploratorium has it covered. But none of this will be on the test. As an early handout noted: “We do not want people to leave with the implied feeling: ‘Isn’t somebody else clever?’ Our exhibits are honest and simple so that no one feels they must be on guard against being fooled or misled.”

Presiding over the magic, either on the shop floor or in a small trailer he shared with his black Labrador, was Frank Oppenheimer. He was the one with the rumpled clothes, the ethereal blue eyes, and the democratic approach to science. Though his brother felt science should be in the hands of the elite. Frank disagreed. We must all dabble in the mysteries of the universe.

“If we stop trying to understand things,” he said, “we’ll all be sunk.”

Frank Oppenheimer died in 1985 but his mind-blowing creation marches on. Along with its website, one of the earliest and most creative, the Exploratorium engages science teachers in numerous outreach programs. High school students, known as Explainers, roam the museum in orange vests offering guidance to the confused. Art installations come and go, with some veterans now boasting MacArthur Genius awards. And various books offer hundreds of diagrams for making experiments.

Like his brother, Frank Oppenheimer remained haunted by the bomb. Each anniversary of Hiroshima, K.C. Cole wrote, he “continued to get a little upset (and a little drunk.) He’d rub his forehead hard, as if he were trying to rub something out.” But from all the fear came a curiosity that has spread around the world. Some 400 science museums worldwide owe their inspiration to the Exploratorium.

“The explorations of science have revealed some of the most amazing sights and undreamed-of novelty,” Oppenheimer wrote. “Perhaps you think that I exaggerate. . . but really, some of the things one sees are so beautiful.”