ROCK OF AGES, CLEFT BY ME

Rock of ages

cleft for me

let me hide myself in thee

— Old hymn

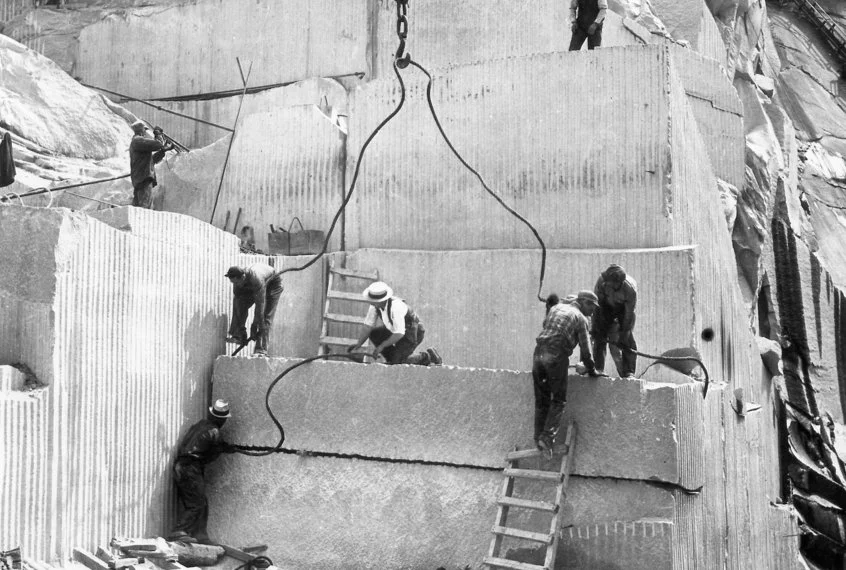

BARRE, VT — 1895 — Shortly after sunrise, on a mountain of grey granite, the hammers ring out. All day, the clang of iron on stone is tempered by the shouts of men — Avantiiii! Attenta! Forzzzaaaa! — and the occasional blast of dynamite.

Skilled granite carvers are coming to Barre for work. They come from Canada, Scotland, Spain, Scandinavia, and especially Italy. The work is brutal — 12 hours a day, six days a week. Earning less than two dollars a day, the men live in boarding houses, two to each nine-by-nine foot room. Each year, a few workers are crushed to death or fall into a pit. Others die of “the stonecutters disease,” silicosis, their lungs choked with fine silica breathed all day. But before dying, they carve their hopes into rock.

Hope Cemetery hosted its first burial in 1896. For several years, the tombstones here were ordinary — flat slabs with the occasional pillar or post. Then in 1903, in Barre’s Socialist Labor Party Hall, Elia Corti was shot and killed. Corti’s brother, a fellow quarryman, began carving his tombstone.

You can read Hope Cemetery as you read a poem. A short pillar suggests a shortened life. A draped urn conveys sorrow, an anchor — hope. Easter lilies symbolize purity. A flame promises eternal life. But what does that soccer ball mean? That race car? That airplane? All prove that the Italians of Barre, Vermont did more than carve granite. They carved their lives.

“A cemetery doesn’t have to be just about grief,” said Amanda Gustin of the Vermont Historical Society. “It can also be a place of beauty.”

Hope is America’s DIY cemetery. Though many of its 10,000 tombstones are ordinary slabs, 75 percent were carved — or designed by — the person who lies beneath. The result is "a gallery of granite artistry" that draws 100,000 visitors a year.

Many come to gawk at the quarries themselves. After more than a century of blasting, carving, hauling, this vein of granite — four miles long, two wide, and ten miles deep — boasts sheer walls of gray and white, with shimmering pools below. Barre calls itself “The Granite Capital of the World,” and one-third of all granite in American memorials came from these quarries, which are still in use.

But just up the road is the cemetery, where men worn down by work found time to plant their own memorials. Some are amusing, some mystical, others just lovely. Each has a story to tell.

William and Gwendolyn Halvosa used to read together in bed every night. But Gwendolyn died young, at 49. Burying his wife in an ordinary grave, William was often seen sitting by her headstone, reading. Then he got busy on a more moving memorial with an epitaph from Song of Solomon 8:6 — “Set me as a seal upon thine heart for love is strong as death."

Even when its population swelled from 2,000 in 1880 to 10,000 by 1900, there was precious little joy in Barre. Saturday night dances, Sunday church, “rolling it lively” when payday came. But when asked “what do people do here for a good time?” one quarrymen scratched his head and replied: “Nothin’ as I know, ‘cept to sleep an’ eat an’ work.”

Oh, but they were in America, right? Better, freer than “the old country.” “As compared with the old country,” one minister said, “the men work harder, receive higher wages, spend more money and are no happier.” With death hovering in dust-filled granite workshops, hope lay in carving a signature upon the earth.

In 1918, when the Spanish flu took a huge toll among the weakened workers, Hope Cemetery began to flourish. The new technology of sand blasting let quarrymen sculpt and carve their dreams into granite. Sharing the work, one man might carve flowers, another add lettering, a third polish the granite to a bright sheen.

The result was "a huge outdoor museum” and a tribute to the human spirit. The Palmisano monument has the Pieta. Look for the Bettini chair and the Ladre cross. Angels abound. The Comolli spire has four. The Brusa monument has a sitting angel. Then there’s the Calcagni colonnade, the Russo ship, the Bianchi Celtic Cross. There are pyramids and poems, a violin, art deco, art nouveau. . .

There used to be an old joke about cemeteries, how people were “dyin’ to get in.” But here on a hillside in Vermont, the joke falls flat. Because these stones are each a rock of ages, “cleft by me.” Some of the stones laugh at death, others weep. But all, like the men that carved them, ring out with the eternal cry — “I am.”