THE FLAGS OF JASPER JOHNS

In the mid-1950s, Main Street was laughing at artists.

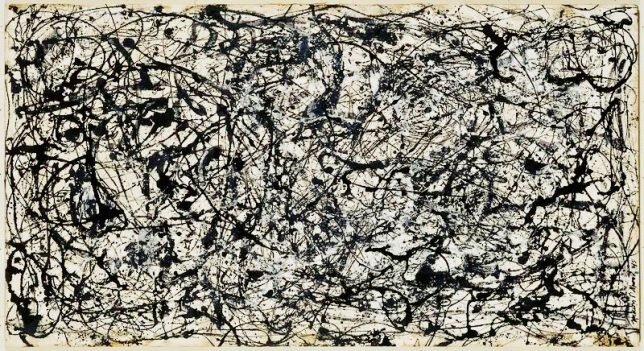

American life was infused with images. Television pumped pictures into living rooms -- cigarettes and cereal boxes, baseball, Beany and Cecil, cowboys and Indians. But American artists had abandoned images. From the splatters of Jackson Pollock to the brooding monoliths of Mark Rothko, Abstract Expressionism ruled the visual arts. A painting shouldn't "mean" anything, Abstract Expressionists said. Painting should channel raw emotion from the subconscious straight to the canvas.

Toward the end of 1957, art dealer Leo Castelli walked the narrow streets of Manhattan near the Brooklyn Bridge to visit his most promising client, Robert Rauschenberg. Rauschenberg's edgy collages had opened a crack in Abstract Expressionism, and Castelli was hoping for more. Seated in Rauschenberg's third floor studio, Castelli decided the two should have a drink. Rauschenberg agreed but did not have any ice. But his friend downstairs had some. Jasper Johns.

"And we went down," Castelli remembered. "And then I was confronted with that miraculous array of unprecedented images -- flags, red, white and blue. . . All white. . . Large ones. . .small ones, targets. . . numbers, alphabets. Just an incredible sight. . . Something one could not imagine, new and out of the blue."

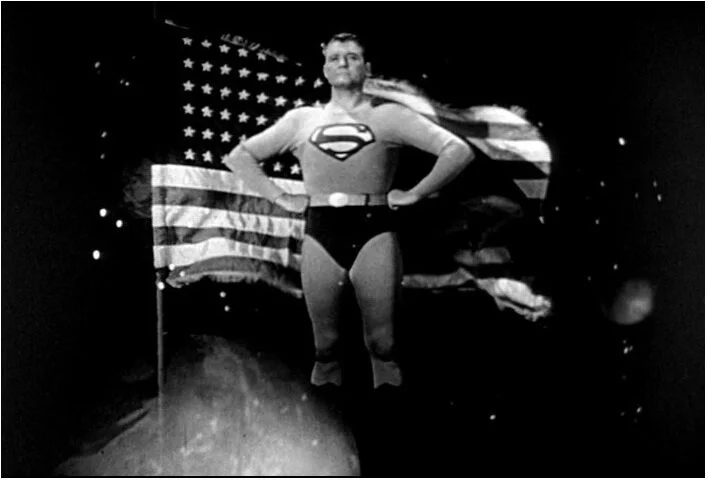

The most startling image Castelli saw that afternoon was the dominant image of the decade -- a flag. In a triumphant America, the stars and stripes were everywhere. Flying from front porches. Soaring above stadiums and state capitols. Unfurled on TV behind Superman who stood for "truth, justice, and the American way." That, however, was on Main Street. What could have induced a New York artist to paint something so mundane, so provincial, so corny as an American flag?

Raised in South Carolina, Jasper Johns had every reason to be alienated from 1950s America. He was a gay man in a time of fierce homophobia. He was a Southerner far from his home turf. And he was an artist, with little desire to imitate the abstract crowd. Johns did not want his work "to be an exposure of my feelings.'' What, then, should he paint?

After two years of menial day jobs and painting on into the night, Johns met Rauschenberg and the two were soon living together. One morning over breakfast, Johns mentioned the strange dream he'd just had -- that he was painting an American flag. Rauschenberg considered it "a really great idea." That afternoon, Johns began.

"Flag," which now hangs in New York's Museum of Modern Art, consists of canvas stretched over plywood, layered with newspaper and slathered with encaustic, a white goo like icing on a cake. As he would for the rest of his career, Johns slaved over the painting. The flag had its own design, freeing him to focus on texture and surface. Upon finishing "Flag," he destroyed all his earlier works and set out to paint "things the mind already knows" -- numbers, letters, a US map -- embellishing the familiar with startling color and texture.

"Johns first astonishes the spectator," one critic wrote, "and then obliges him to examine for the first time the visual qualities of a humdrum object he had never before paused to look at." Artist Fairfield Porter added, "He looks for the first time, like a child."

On that afternoon in 1957, even before getting ice, Castelli offered Johns a one-man show. Within six months, Jasper Johns was, TIME magazine said, ''the brand-new darling of the art world's bright, brittle avant-garde.'' "Flag" ended the disconnect between artists and American imagery. Soon would come soup cans, comic panels, and other Pop Art. And for Johns, flags became a motif he would explore for two decades.

The flags of Jasper Johns come in various sizes, colors, and media. The artist's motives, however, remain mysterious. Beyond his dream, Johns has said nothing about why he painted the stars and stripes again and again. Some critics say Johns' flags are anti-patriotic, thumbing their nose at the ubiquitous flags in American life. Others say his Southern roots proved deeper than he imagined. The mystery leaves only the flags, and "Flag" to offer interpretations.

"Flag" at its simplest promotes the history you were taught to revere, the stars and stripes celebrating "liberty and justice for all." But beneath is the darker, deeper history of injustice and inequality, of events whose headlines are best hinted at. Inspiring and disquieting, hopeful yet cautious, this is America on canvas -- a giant "YES!" meeting a whispered "but. . ." In a single painting, Jasper Johns, son of the South, rebel within the art world, embodied America in its most potent symbol.

"No other nation treats its flag the way Americans do theirs," critic Robert Hughes noted. "It is a peculiarly sacred object. You must handle it with care, fold it in a ritually specified way, salute it, and never allow it to touch the ground. To burn or deface it is a supercharged political act... But on the other hand, Americans make jeans, T-shirts, and underwear out of it, and use it to advertise everything from gas stations to hot dog stands."

A symbol became an artwork. An artwork became an icon. Six decades after it hung in a second floor studio, "Flag" is still America on canvas, with icing.