SILENT SENTINELS

THE WHITE HOUSE — JANUARY 1917 — From 1848 until World War I, American women argued for the right to vote. Speeches rang out. Conventions met and shouted. And still, half of all American adults could not vote. Then on a snowy January morning in 1917, a dozen women dressed in white walked to the gates of the White House. All day they stood. And the next day, and the next. . . In the drifting snow, only their banners spoke.

Until 1917, no one had ever picketed the White House. But then, no previous suffragists had driven coast-to-coast caravans, sent birthday cakes to Congressmen, or lobbied with the strategic genius that rivaled the Founding Fathers. These tactics, scorned by some women, were the inspiration of one.

Susan B. Anthony has her own coin. Elizabeth Cady Stanton, likewise, is in the history books. But until recently, few Americans had heard of Alice Paul. Shy, reclusive, penning no memoir, Alice Paul had, one admirer noted, "the quiet of the spinning top." Yet with dedication and grit, she revived the suffrage movement and drove it to the ballot box.

Paul's path to suffrage ran from her Quaker childhood in New Jersey through her early work in a New York settlement house. "My main impression of poverty work was the hopelessness of it all," she said. "It seemed we were always burying children." A scholarship to study in England changed her life, and American politics.

When Paul went to England in 1907, she saw that British suffragists (above) were not giving speeches. They were breaking windows, setting fires, waging hunger strikes. Paul disapproved of the violence but having read Thoreau, she was drawn to civil disobedience. Arrested in England, she waged her first hunger strike. Months later, when she returned to America, the suffragist movement had, depending on one's politics, its Lincoln or its Lenin.

Creating a new National Woman's Party, Paul plotted high profile actions. A suffrage parade in Washington, DC drew a half million onlookers. Follow-up parades around the nation kept the limelight. Paul garnered backing from Theodore Roosevelt and Supreme Court justice Louis Brandeis. But her bullseye was Congress, where she soon disproved the notion that women were unfit for politics.

NWP lobbyists kept a card catalog with details about every Congressman. Meeting politicians, Paul's lobbyists quoted their speeches, mentioned wives and daughters who might disagree, and penned Valentine rhymes based on their voting records. Any Congressman who said the folks back home opposed suffrage soon saw a NWP rally -- back home.

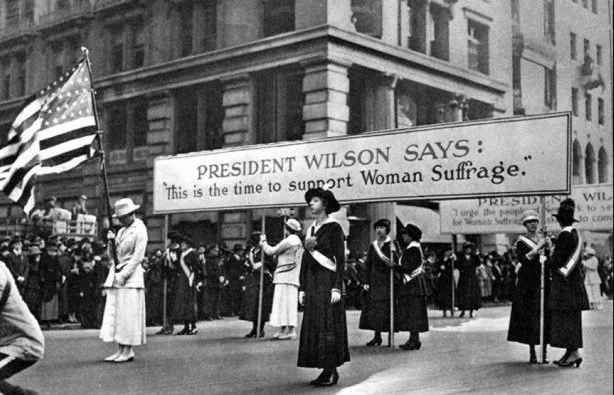

The NWP dogged President Woodrow Wilson, unfolding banners wherever he spoke, shouting as he passed, meeting him in the Oval Office. Finally, when nothing changed the president's mind, the Silent Sentinels planted themselves outside his house. When the embarrassed president invited them in out of the cold, they declined.

On through the winter, they stood and stood. The stodgy New York Times called them "silent, silly, and offensive." Men hurled insults or rotten fruit. Angry cops tore down their banner reading "Kaiser Wilson." Then in June, DC officials wrote to Paul, "We have to say to you, if you do persist, that we have no alternative except to arrest you." Nevertheless, they persisted.

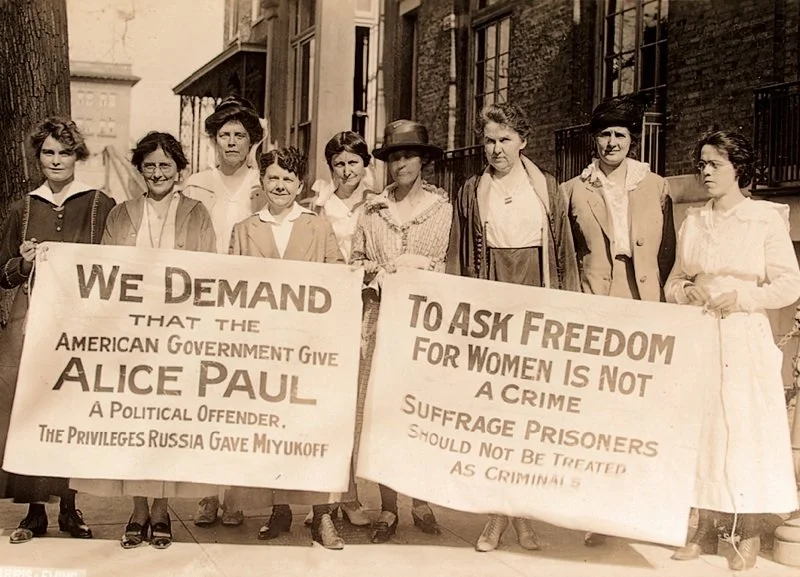

What followed was too ugly for the history books. Arrests. Jail. Hunger strikes. Force feeding with tubes pumping gruel through the nose. A "Night of Terror" when guards beat women. But such savagery, when leaked to the press, proved too ugly for America. Public pressure mounted. On Nov. 27, 1917, the Silent Sentinels were released. "They tried to terrorize and suppress us," a weakened Paul said. "They could not, so they freed us."

Two weeks later, the House again took up the Susan B. Anthony amendment. A chastened President Wilson called it "an act of right and justice." And the president changed his mind.

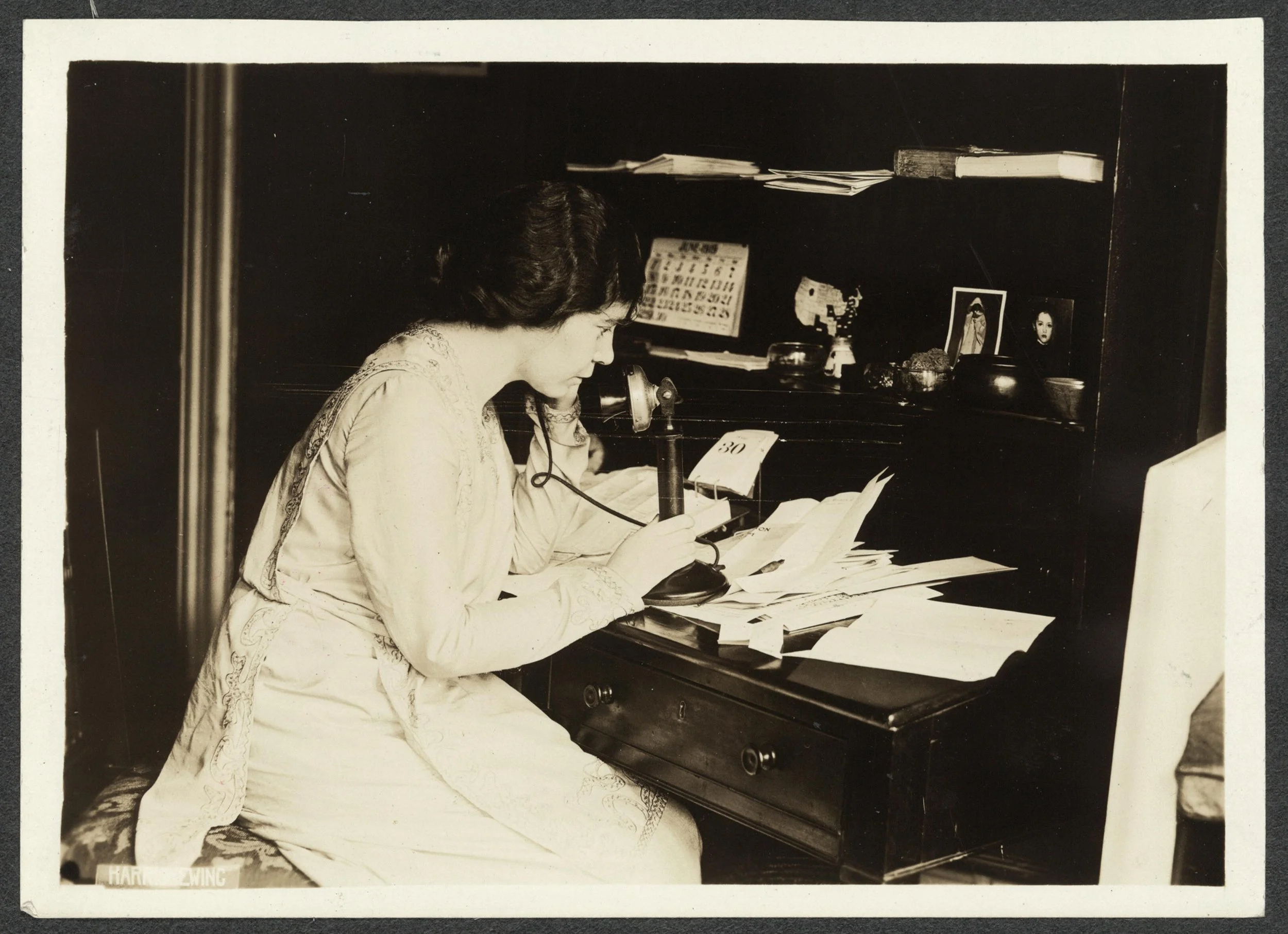

"The president has succumbed to the pickets," the Baltimore Sun announced. The next day, one year to the day after the Silent Sentinels took their stand, the amendment passed the House. Suffragists in the gallery wept. Back at NWP headquarters, they found Alice Paul at her desk. "Eleven to win before we can pass the Senate," she said.

Finally. . .

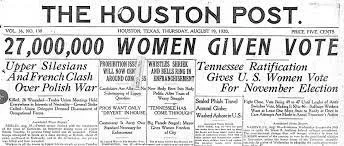

On August 18, 1920, the 19th amendment gave women the vote. "We all know who passed the federal amendment," one suffragist wrote. "It was little Alice Paul."

In 1923, Alice Paul introduced the Equal Rights Amendment before Congress. Forty-nine years later, it passed both houses. When she died in 1977, little-known as she preferred to be, the ERA was gaining momentum. In1982, it fell short, but efforts to pass it are gaining momentum. Persist.