VICTORIA FOR PRESIDENT -- IN 1872

MANHATTAN — 1870 — It was an off-year election, but voter fraud was expected.

On that brisk November morning, three women gather in a posh Manhattan brownstone. When the ladies are seated, one recites the 14th amendment. "No state shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States. . ." All agree that the stirring words, recently added to the Constitution, give the vote to all citizens. Grabbing their coats, the women ride a horse drawn carriage to the polling place.

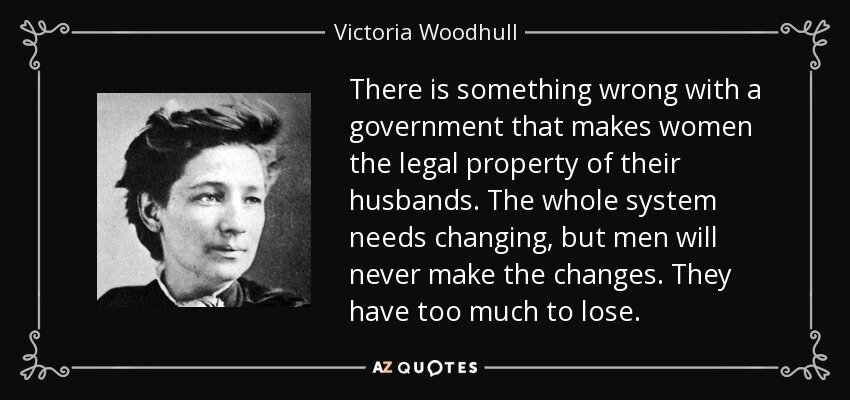

A crowd has gathered outside to see "Mrs. Satan" and her "irresistible" sister. Oblivious to the attention, Victoria Woodhull and Tennessee Claflin march inside. Striding to the ballot box, Mrs. Woodhull presents proof of her registration. She is not given a ballot. "Mrs. Woodhull's indignation," the New York World recorded, "was scarcely controllable." There will soon be another presidential election, she notes. And she will not just vote. She will run for president.

American history holds few women -- or men -- to rival the daring of Victoria Claflin Woodhull. During the 1870s she defied every double standard against women. Along with being the first woman to run for president, she was the first female broker on Wall Street, the first woman to run a newspaper, and the first to address Congress. But her American pedigree comes not from "firsts" but from her spirit -- a blend of grit, honesty, and faith in the future. "They cannot roll back the rising tide of reform," she often said. "The world moves."

Back in the 1840s, folks in Homer, Ohio, didn't much care for the Claflin clan. Buck Claflin committed petty crimes to support his brood. Meanwhile his wife Anna taught her ten children to summon the spirit world. So in 1850, when Americans began flocking to séances, Buck Claflin put his daughters to work.

Within weeks, eleven-year-old Victoria and seven-year-old Tennessee (above) were supporting the family by telling fortunes. Victoria was soon married, soon disillusioned. "I supposed that to marry was to be transported to a heaven not only of happiness but of purity and perfection," she later said. "I soon learned that what I had believed of marriage and society was the nearest sham."

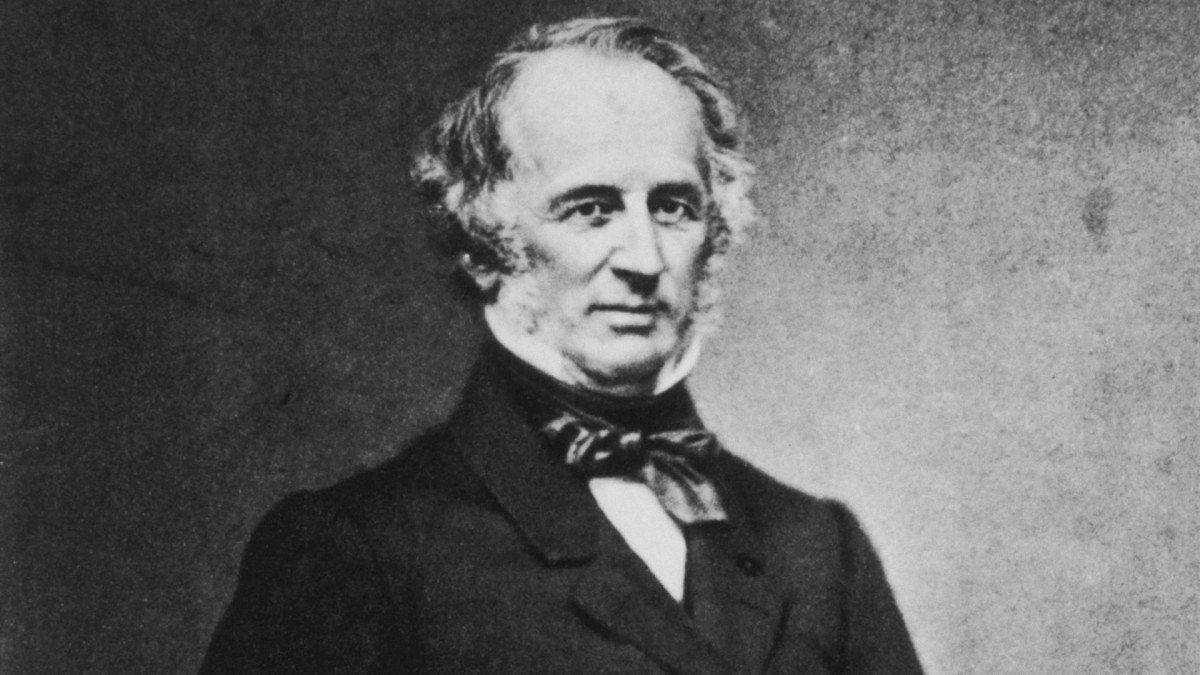

Married to a dissolute alcoholic, Victoria doubled down on herself. For the next decade, as the nation marched through the Civil War, Victoria and Tennessee roamed the Midwest on the spiritualist circuit. By 1868, they had enough money to move to Manhattan. There they met Cornelius Vanderbilt.

Recently widowed, the crotchety shipping tycoon admired Victoria for her fortune telling, which he used to buy stocks, and Tennessee for her beauty. He called Tennessee "Little Sparrow" and proposed. She called him "Old Boy" and refused. But the sisters did not refuse Vanderbilt's offer to get them into the men's club called Wall Street.

In 1869, a "panic" crashed the gold market. Victoria set up a carriage outside the gold exchange, offered advice, then bought deflated stocks. She made $700,000, then stunned Wall Street by opening a brokerage -- Woodhull and Claflin. On the sisters' first day in business, 4,000 dropped in to see women buying and selling stock. "Petticoats Among the Bovine and Ursine Animals," the New York Sun headlined. Though the novelty wore off, Woodhull and Claflin continued to make good money, and to earn brokers’ respect.

Famous now, Victoria began writing for the New York Herald. In her first column, she declared her immodest ambition. "While others of my sex devoted themselves to a crusade against the laws that shackle the women of the country, I asserted my individual independence. . . I now announce myself as candidate for the Presidency." A month later, she was touting her candidacy in Woodhull and Claflin's Weekly.

For the next year, Victoria made news. "Of the three distinguished candidates for the White House yet named," a Michigan paper wrote, "Mrs. Woodhull is the best man, by all odds." Change was in the air, Victoria told growing crowds. Democrats and Republicans were "parties of the past."

On May 10, 1872, the Equal Rights Party held its convention in Manhattan. Shortly after noon, wearing a black dress and blue tie, Victoria approached center stage. A voice boomed: "The choice of the Equal Rights Party for President of the United States, Victoria C. Woodhull!" Five minutes of cheering followed. Once Mrs. Woodhull accepted the nomination, the convention chose Frederick Douglass for vice-president. Douglass never acknowledged the nomination, but that was just the start of the trouble.

On the stump, Victoria advocated women's rights, including the "natural right to love whom I may, to love as long or as short a period as I can." Men had that right. Why shouldn't women? Why should laws governing marriage favor men? Why should there even be laws governing marriage? "Do you not perceive that the law has nothing to do with continuing the relations which are based on continuous love?"

Word spread that Victoria Woodhull was living with two husbands! (Though divorced and remarried, she was still caring for her hapless first husband.) Scandalous rumors of “free love” led to boos and hisses at her lectures. Evicted from her brownstone, she slept in the offices of Woodhull and Clalfin. Business, too, dried up. But the final blow came when she learned of an affair involving the leading preacher of the day, Henry Ward Beecher.

Shortly before the election, Woodhull and Claflin's Weekly broke the story of the affair. Arrested on obscenity charges, Victoria spent Election Day in jail. The Equal Rights Party made the ballot in twenty-two states but in most, the name Victoria C. Woodhull was absent. Seems that along with being a woman, she was thirty-four, too young to run for president.

"Mrs. Satan" paid a heavy price for her audacity. In 1875, Henry Ward Beecher was tried for adultery. A hung jury resulted. Then Cornelius Vanderbilt died. His son offered Victoria and Tennessee part of the inheritance, providing they left the country. The sisters spent the rest of their lives in London. Victoria married a third time and started a progressive school. The sisters lived on into their eighties.

When Victoria died in 1927, the London Times obit read "the younger generation knows not this indomitable leader to whom their enfranchisement owes so much." By then, women could be found occasionally on Wall Street and everywhere in the voting booth. But the White House?

"They cannot roll back the rising tide of reform. The world moves."