NELLIE ON THE FLY

We sip Chardonnay as we soar at 30,000 feet. We skim over the globe — Rome, Paris, London — then say we’ve seen the world. This is travel in the 21st century. But the 19th century hungered for adventure. Explorers returned from Africa or the “Far East” with stories that thrilled millions. Men, all were men. Except. . .

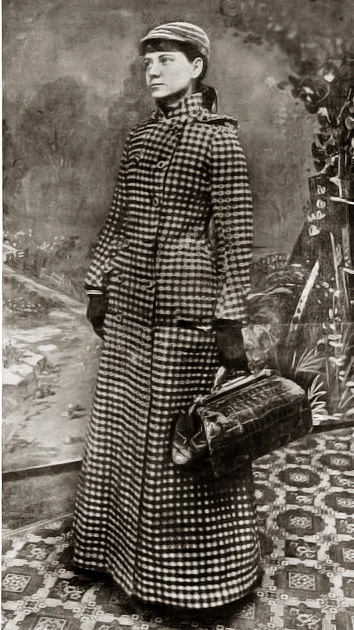

On November 14, 1889, a 25-year-old journalist stood on the deck of the Augustus Victoria as it steamed passed the new Statue of Liberty. She had a small bag, £200 in gold, and unflappable nerve. Jules Verne’s fictional Phileas Fogg had gone Around the World in 80 Days. Nellie Bly claimed she could circle the globe even faster.

“Impossible, was the terrible verdict,” she recalled. “'In the first place you are a woman and would need a protector, and even if it were possible for you to travel alone you would need to carry so much baggage that it would detain you in making rapid changes.’” Only a man could do it, they huffed. “'Very well,' I said angrily. 'Start the man, and I'll start the same day for some other newspaper and beat him.'"

She was born Elizabeth Jane Cochrane, the 13th child of an American Dreamer. Her Irish father had worked his way up from blacksmith to real estate tycoon. But when Elizabeth Jane was six, Michael Cochrane died without a will. Suddenly impoverished, she helped her mother run a boarding house and might have spent her life there but for an article in the Pittsburgh Dispatch headlined “What Girls are For?”

To cook and clean and breed, of course. Enraged, Elizabeth wrote a fiery response. Girls should have the same opportunities as boys — interesting work and (gasp!) equal pay. She signed her letter “Lonely Orphan Girl,” but the Dispatch editor learned her real name and hired her. In newspapers’ macho milieu, the few female reporters took pseudonyms, and “Nellie Bly” was soon reporting on shocking conditions in Pittsburgh’s factories.

When factory owners’ protests relegated her to the women’s page, she quit. Then, determined to “do something no girl has done before,” she became a freelancer, roaming Mexico and sending back dispatches. By 1888, she had talked her way into a job at Joseph Pulitzer’s New York World.

With newspapers as America’s only media, competition was fierce. Nellie Bly knew what readers wanted – truth, justice, and a great story. She posed as a maid struggling on a meager salary. She went up in a balloon and undersea in a diving bell. And in the assignment that made her name, she feigned madness and was committed to the Women’s Lunatic Asylum on New York’s Blackwell’s Island.

Inside the asylum, she sat on hard benches, roped to another inmate. She ate gruel, fought off rats and suffered ice water baths. “What excepting torture,” she wrote, “would produce insanity quicker than this treatment?” Her riveting report from this “human rat trap” led to a grand jury investigation and reform. For the rest of her career, the name “Nellie Bly” would be included in every headline above her articles. But when she set off around the globe, all of America watched.

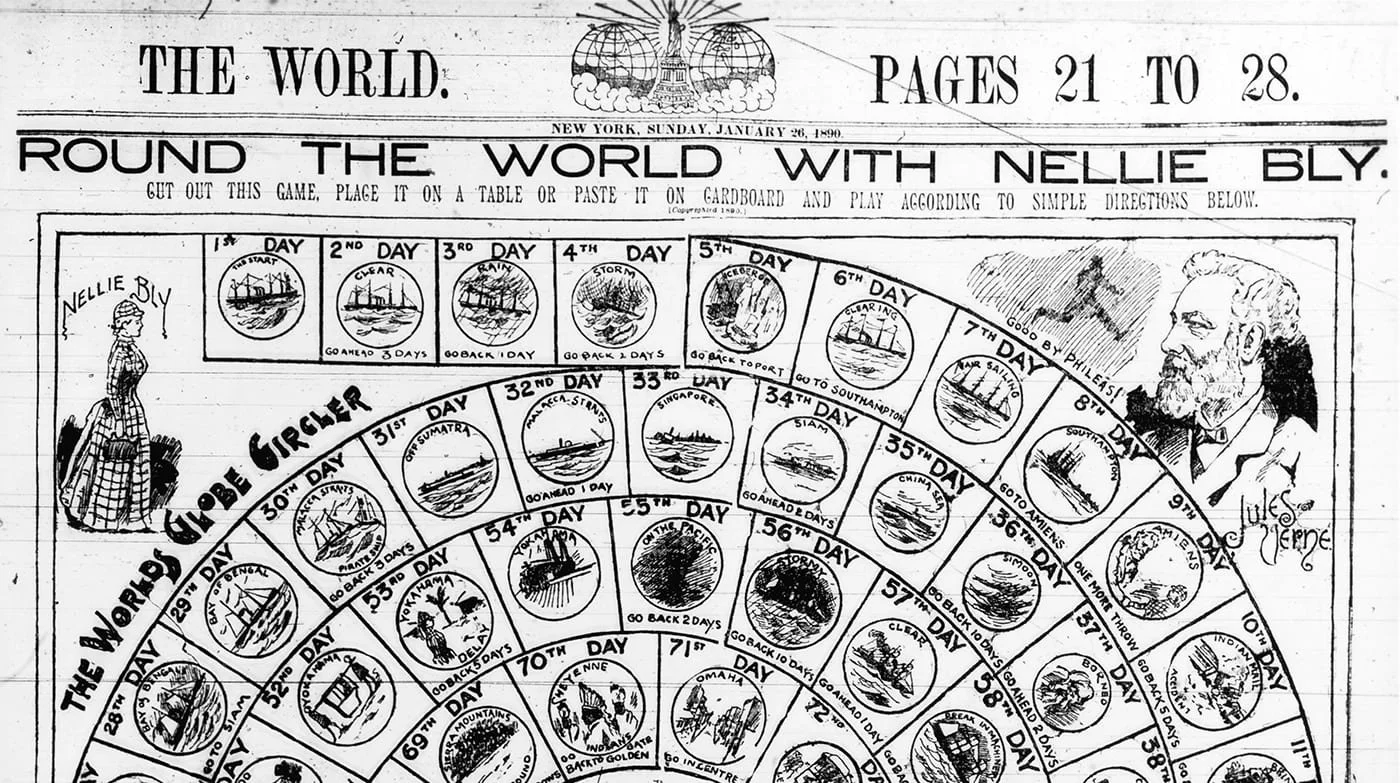

“Nellie Bly is Off!” the World announced. After an uneventful Atlantic crossing, Bly ferried across the English Channel. In France, she met and charmed Jules Verne, then rode a train down the length of Italy. In Brindisi, another ship took her on through the Suez Canal. Wherever possible, she cabled or telegraphed news of her progress. The World ran a contest asking readers to guess the exact time she would return. A half million entries poured in.

Heat. Insects. Marriage proposals. Monsoons and madmen. Beggars and bandits. Nellie Bly kept moving, kept moving. From the port of Aden across the Indian Ocean to Ceylon. From Ceylon to Singapore, where she bought a monkey that would travel on with her.

By early January 1890, her 80-day deadline loomed. Then in Hong Kong, she learned she was being raced. A reporter for New York’s Cosmopolitan was circling the globe westbound. Bly scoffed at the news. “I would not race,” she said. “If someone else wants to do the trip in less time, that is their concern.” But she booked the next boat across the Pacific, arriving in San Francisco two days ahead of schedule.

The home stretch was a celebration. Joseph Pulitzer chartered a train that took “Nellie on the fly” across America. Crowds met “the World’s globe girdler” on arrival. Brass bands. Flowers. Fireworks.

At precisely 3:51 p.m. on January 25, 1890, Bly’s train pulled into Jersey City. She had expected the journey to take 75 days. Her time: 72 days, six hours, 11 minutes, 14 seconds. The fastest circumnavigation so far. “The stagecoach days are ended,” the World announced. “The new age of lightning travel has begun.”

Nellie Bly was world famous, yet with a tough act to follow. In 1895 she married a man twice her age and retired from journalism. When her husband died, she ran his factory, only returning to newspapers after his death. She reported from Austria during World War I, headlined “Nellie Bly on the Firing Line!”

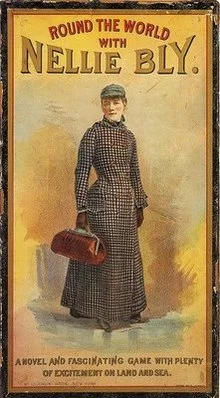

In 1922, at age 57, she died of pneumonia. By then her name had graced a railroad car, a racing horse, trading cards, a children’s board game, and headline after headline. She was also remembered in a popular verse:

I wonder when they'll send a girl to travel around the sky.

Read the answer in the stars, they wait for Nellie Bly.