MR. FEYNMAN GOES TO WASHINGTON

PASADENA, CA — 1986 — A few days after the Challenger space shuttle traced caterpillars of smoke across the Florida sky, Richard Feynman got a call from Washington, D.C.

Would he come to the nation’s capital to help investigate the disaster? The distinguished panel would include Neil Armstrong, Sally Ride, and test-pilot Chuck Yeager. Feynman refused. “You’re ruining my life,” he told commission chair William Rogers. But he did not tell Rogers how little life he had left.

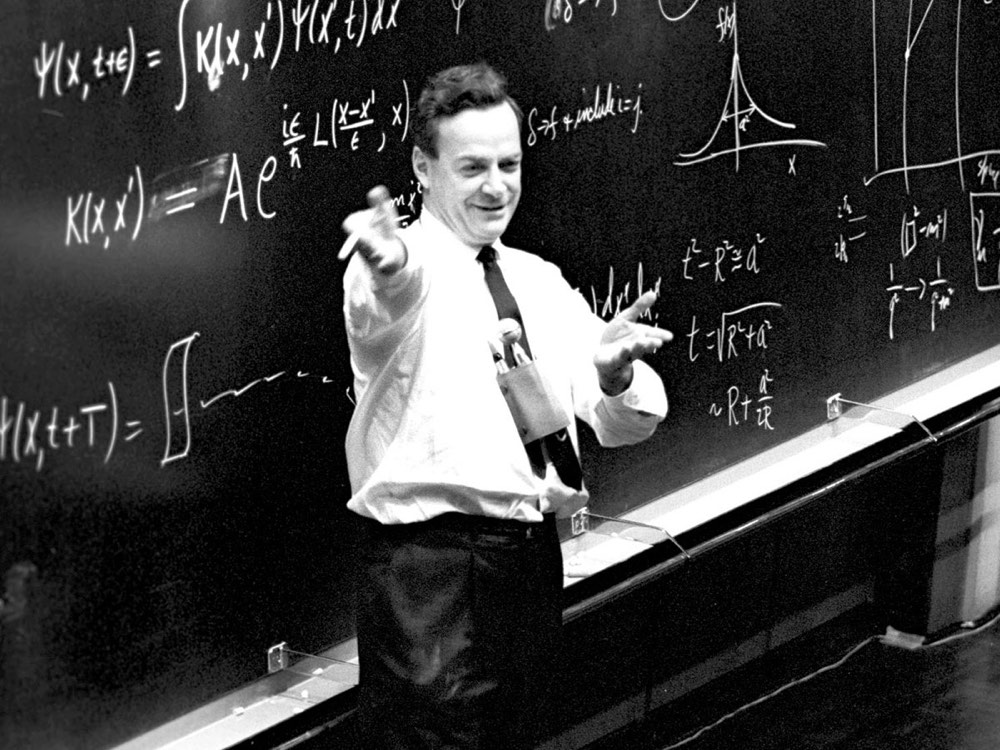

Richard Feynman was a “curious character.” An unlikely mix of New York street sass and Princeton Ph.D., Feynman peppered his lectures with words like “screwy,” “dopey,” and “absurd.” The public did not know him — yet — but Feynman was a legend among physicists.

From his early work on the Manhattan Project, where J. Robert Oppenheimer called him “the most brilliant young physicist here,” to the foggy fields of quantum physics, Feynman was “a magician of the highest caliber.” His Nobel winning theory of light and matter — quantum electrodynamics — helped lasers evolve from lab toys into tools of light. Yet Feynman was also “a showman. . . as though Groucho Marx were suddenly standing in for a great scientist.”

(ATTEND A FEYNMAN LECTURE -- SEE BELOW.)

Feynman called his antics "aggressive dopiness." He was proud of his bongo playing and safe cracking, taking LSD and speaking, barefoot, to New Age zealots in Big Sur. Since the late 1970s, however, he had also battled cancer. He survived one bout, but another in 1985 left him ashen. He did not want to go to Washington.

The nation’s capital, he told his wife, was “a great big world of mystery to me, with tremendous forces.” She convinced him to go, saying he might discover something others overlooked. Even before he left Caltech, Feynman was making discoveries.

“O-rings show scorching in Clovis check,” he scribbled in a notebook. “Once a small hole burns through generates a large hole very fast! Few seconds catastrophic failure.” Wary of politics but determined to get at the truth, he flew to DC.

The Nobel laureate immediately clashed with DC culture. A four-star general on the Challenger commission told him to comb his hair. No one wanted to blame NASA, but Feynman probed NASA officials until asked to back off. One weekend, he flew to NASA facilities to interview engineers. He was appalled.

NASA had been warned. The night before the fateful launch, engineers expressed concern that the shuttle's rubber O-rings would stiffen in cold, breaking their seal. NASA launched anyway. Feynman saw an agency, pressured by its launch schedule, playing “Russian roulette” with shuttle safety. Just because the first click didn’t kill you. . .

Back in DC, Feynman wrote up his findings. Furious, Chairman Rogers ordered Feynman to tone it down. The public had to trust NASA. Feynman refused. Then he pulled a magic trick.

En route to a final hearing, Feynman asked his taxi driver to find a hardware store. He rushed in and bought pliers and a C-clamp. At the hearing, he asked for ice water. After a few bland questions, he turned on his mike to speak but Rogers quickly called a recess. In the men’s room, the chairman told Neil Armstrong, “Feynman is becoming a real pain the ass.”

When the meeting re-convened, Rogers let Feynman speak. Greyed and grizzled, the legend held up pliers and C-clamp. Then with cameras rolling, he dropped a piece of O-ring into his ice water. Watch.

“And I discovered that when you put some pressure on it for a while and then undo it, it doesn’t stretch back. It stays the same dimension. In other words, for a few seconds at least and more seconds than that, there is no resilience in this particular material when it is at a temperature of 32 degrees. I believe that has some significance for our problem.”

That night, TV news aired Feynman’s experiment, giving America a science lesson. “The public saw with their own eyes how science is done,” physicist Freeman Dyson said.

Feynman’s rogue report became an appendix to the commission’s study, which largely forgave NASA. After a ceremony in the Rose Garden, Feynman went home to Pasadena. Two operations that fall removed tumors, but he died in February 1988.

In the decades since, his humor and genius have turned Feynman into a cult figure, the subject of an opera, a graphic novel, biographies, and books of his lectures. But along with “aggressive dopiness,” he left a final lesson, from his Challenger report:

“For a successful technology, reality must take precedence over public relations, for nature cannot be fooled.”

(CLICK HERE TO ATTEND A FEYNMAN LECTURE.)