WHEN TESS AND RAY TALKED ABOUT LOVE

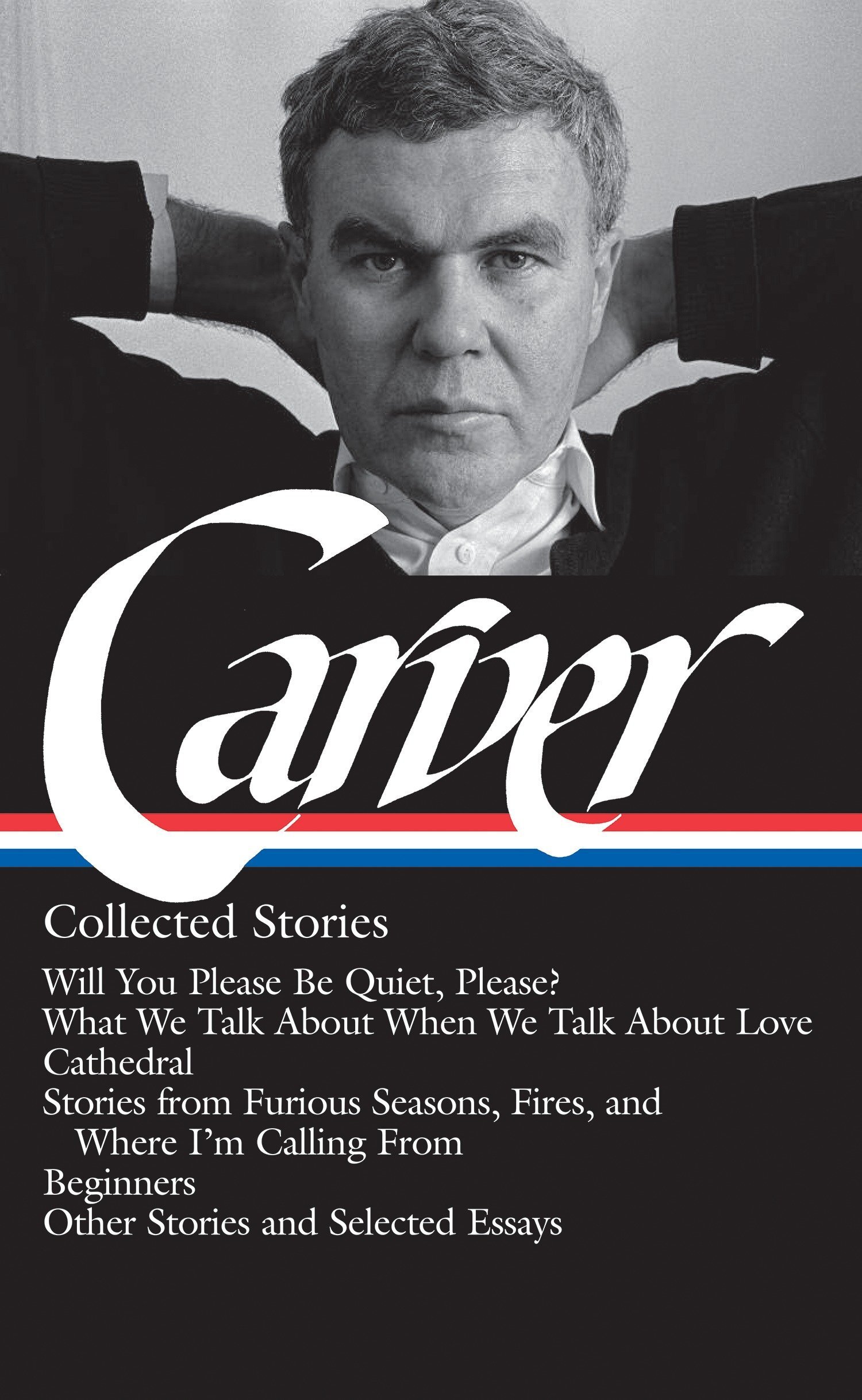

In a Hollywood romance, you know the ending. Happily ever after. But this is a Raymond Carver story. Readers who know that term know the story may not end well, but it will be tough, tender, and human.

“Hooked on writing stories,” Raymond Carver was also hooked on the bottle. A hardscrabble youth in rural regon saw him marry at 18, then struggle to support a wife and children. He was a janitor, doing his chores in an hour so he could write for hours more. He was a delivery man. He worked in a sawmill. Studying his craft in writing workshops, he published a few stories, but by 1970, the man he called “Bad Ray” was plotting his life. Binges and blackouts, stumbling, stashing bottles.

“I’d given up entirely,” he remembered. “Thrown it in and was looking forward to dying, that release.”

Alcohol loved him but readers did not. Americans preferred the middle class milieu of John Updike, the conflicted sages of Saul Bellow, the zany wit of Barthelme and Barth. Who cared about these people Ray Carver knew so well — drunks, divorcees, down and outs?

In 1976, Carver touched bottom but saw a light above. His first collection, Will You Please Be Quiet, Please? sold poorly but was nominated for a National Book Award. Over a Bloody Mary breakfast, a publisher offered Carver an advance for a novel. He went to the restroom and wept.

On his way back to the table, he downed a double on the rocks. Accepting the offer, he started a novel that went nowhere. Back to the bottle. Finally, he joined Alcoholics Anonymous, and in June 1977, took his last drink. Six months later, at a writer’s conference, he met Tess Gallagher.

She rode horses, wore exotic hats, sang ballads in Gaelic. She knew the demons of alcohol, schooled by her father and ex-husbands. But smitten by this burly, disheveled man who wrote such stories, she felt “as if my life until then had simply been a rehearsal for meeting him.”

Ray and Maryann Carver had been fighting like characters in a Raymond Carver story. Twenty years of marriage had taken them “through a shipwreck. We can’t help each other now,” he wrote to her. “We need help.”

After Maryann kindly “stepped aside,” Tess visited Ray in El Paso, where he was teaching. “He hugged me like a man sinking,” she recalled. Following a winter of roses (she sent them) plus letters and long distance calls, Tess moved in.

Once Raymond Carver “chose to live,” Tess remembered, “the leopard of his imagination pulled down the feathers and blooded flesh of stories fueled by his previous failures.” In the next decade Carver wrote as many stories as he had in the previous two, plus 200 poems. In some stories, he found the Everyday and in others he found magic.

In “Cathedral,” a man is asked to describe a cathedral to a blind friend of his wife’s. In “A Small, Good Thing,” Carver turns the tragedy of a boy’s death into a revelation. And in “What We Talk About When We Talk About Love,” couples discuss the vagaries of love over “cheapo gin” and a sunset.

Suddenly Carver found himself compared to Hemingway and Stephen Crane, his stories labeled “masterpieces.” Saturday Review called his prose “as sparingly clear as a fifth of iced Smirnoff.” Carver won a five-year grant to nothing but write. Tess wrote along with him, publishing poems in the New Yorker and elsewhere.

Critics found Carver’s characters tough to love but America knew them well. Carver was not surprised. “The waitress, the bus driver, the mechanic, the hotel keeper. God, the country is filled with these people. They’re good people. People doing the best they could.”

Tess and Ray moved to Port Angeles, Washington, and bought a house overlooking the North Cascades, They seemed to hold the same pen, the same spirit. “There was no question that Ray was in love with Tess,” a friend noted. “He was the kind of guy who couldn’t tie his own shoes. He was awkward and bumbling, didn’t quite know anything about practical life. After she came and set up the house for them, Ray was happy.”

Hollywood would end it here, but this is a Raymond Carver story. . .

Despite beating the bottle, Carver could not quit smoking. In the summer of 1987, he began coughing, spitting up blood. He fought his fate for a year, writing and giving readings where he wheezed as much as spoke. In June 1988, Tess and Ray bought rings and flew to Reno to get married. She won big at roulette and they marveled at their luck, luck for a day, luck for their time together. He called those ten years “gravy.”

Two months later, confined to a hospital bed in his home, Carver stayed up one night with a friend. At dawn, Tess found him breathing slowly. She held him as he died. He was 50. Carver was buried in a nearby cemetery, a small, good service. On his gravestone, Tess put his poem, “Late Fragment.”

And did you get what

you wanted from this life, even so?

I did.

And what did you want?

To call myself beloved, to feel myself

beloved on the earth.