THE LOVING COUPLE

In July 1958, in the dead of night, a sheriff in rural Virginia banged on a couple’s door. Then the sheriff burst in. Flashlight blazing, he stood beside the bed.

“Who is this woman you’re sleeping with?”

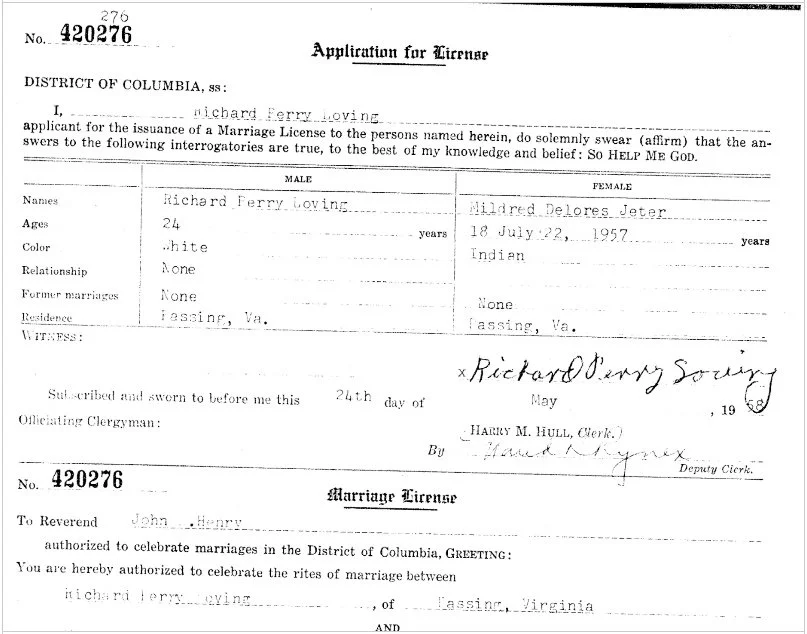

“I’m his wife,” the woman said, pointing to the marriage certificate on the wall.

“That’s no good here!” the sheriff barked. And within the hour, Richard and Mildred Loving were in jail. Because he was white. She was “colored.”

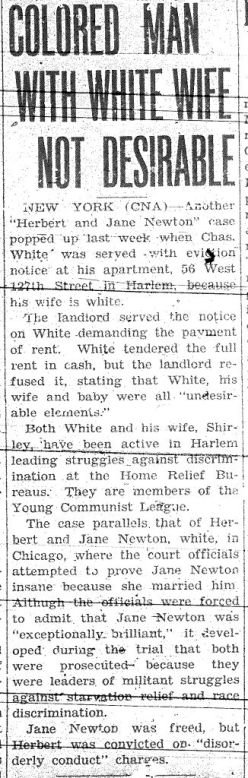

In 1958, forty-two states had laws against inter-racial marriage and half still enforced them. But when the Loving couple violated Virginia’s Racial Purity Act, they started a sea change in American romance.

Richard and Mildred met in Central Point, an hour north of Richmond. A crossroads in rural Caroline County, Central Point tiptoed around Jim Crow. “There’s just a few people that live in this community,” Richard said. “A few white and a few colored. And as I grew up, and as they grew up we all helped one another. It was all, as I say, mixed together to start with and just kept goin’ that way.”

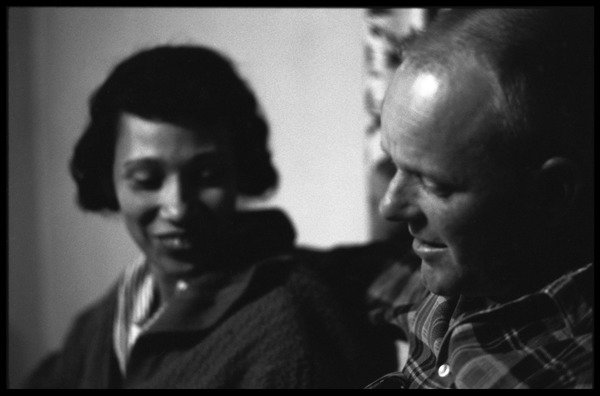

So no one, black or white, said much when Richard Loving and Mildred Jeter began dating. They seemed a curious couple. She was gentle and charming; he was gruff and tight-lipped. But friends found Richard “equally comfortable with people in any setting. He could blend and mix with any people.”

When she got pregnant, they went to Washington, D.C. to get married. Certificate in hand, they came home. Then, Richard said, “someone talked.” The Lovings were sentenced to a year in prison unless. . . The sentence would be suspended if they left Virginia and did not return. The couple moved to DC and had three children. They were miserable.

“The children didn’t have anywhere to play,” Mildred said. “It was like being caged. And I couldn’t stand it.”

After four years, occasionally slipping home under cover to visit family, Mildred wrote to Attorney General Robert Kennedy. He referred her to the American Civil Liberties Union. ACLU lawyers found Mildred “instantly likable.” But Richard “looked like a redneck,” one said. “He even had a red neck.” Still, lawyers noticed “what everyone says — they were very much in love.”

When they filed an appeal, lawyers could scarcely believe the judge’s summation: “Almighty God created the races white, black, yellow, Malay and red, and He placed them on separate continents. . . The fact that He separated the races shows that He did not intend for the races to mix.”

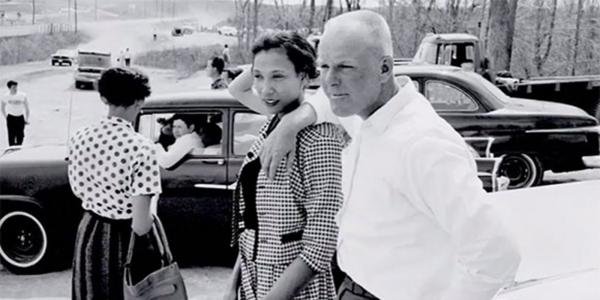

Stuck in DC, the Lovings entered legal limbo. Intensely private people, they were surrounded by cameras and reporters. On and on the ordeal went. Motions, appeals, sign here. Neither wanted to be a test case. “We were trying to get back to Virginia,” Mildred said. “That was our goal.” Richard, when explained some technicalities, said, “That stuff don't mean nothin’ to me. Mr. Cohen, tell the Court I love my wife, and it is just unfair that I can't live with her in Virginia."

In April 1967, Loving v. Virginia reached the Supreme Court. “You have before you today,” Bernhard Cohen began, “what we consider the most odious of the segregation laws and the slavery laws." But beyond the law, Cohen also shared Richard’s statement: “Tell the Court I love my wife. . .”

On June 12, 1967, the court ruled: “The freedom to marry has long been recognized as one of the vital personal rights essential to the orderly pursuit of happiness. To deny this fundamental freedom on so unsupportable a basis as the racial classifications. . .” The decision was unanimous.

After eight years in exile, Richard and Mildred finally moved back to Virginia. He built a cinder block house and they settled in, happy to be together, happy to be forgotten. But the case was not forgotten. Unlike Brown v. Board of Education, stonewalled for a decade, Loving v. Virginia changed lives and loves.

In some Southern states, within just a few years, interracial marriages quadrupled. Nationwide the rate went from 1 percent in 1967 to 16 percent today.

Richard and Mildred did not have many years together. In 1975, he was killed by a drunk driver. Mildred lived on, keeping quiet about her place in history. Then in 2007, on the case’s 40th anniversary, she spoke out.

“Surrounded as I am now by wonderful children and grandchildren, not a day goes by that I don't think of Richard and our love, our right to marry. . . I am still not a political person, but I am proud that Richard's and my name is on a court case that can help reinforce the love, the commitment, the fairness, and the family that so many people, black or white, young or old, gay or straight seek in life. I support the freedom to marry for all. That's what Loving, and loving, are all about.”

Mildred Loving died a year later. She is buried beside Richard just down the road from the house he built for them.