MARIAN ANDERSON AND THE CONCERT THAT STIRRED AMERICA

She had, one composer said, “a voice heard once in a hundred years.” Listen.

By the late 1930s, Marian Anderson’s soaring contralto had lifted her from a Philadelphia ghetto to the concert stages of Europe. Audiences swooned. Sweden had “Marian fever.” Others praised her presence as angelic and her voice as “peculiarly captivating.” But 80 years ago this spring, when she planned a concert near the White House, America faced its darkest demon.

“The rules governing the use of Constitution Hall,” snooted the president of the Daughters of the American Revolution, “are in accordance with the policies of theaters, auditoriums, hotels and public schools of the District of Columbia.”

Like all other theaters in DC and further south, Constitution Hall was segregated. Blacks sat in rear seats, whites in front. And no “colored” singer, regardless of acclaim, would sing in Constitution Hall so long as the D.A.R. owned it.

Throughout February 1939, the controversy mounted behind the scenes. While Anderson sang to thousands across the Midwest, her manager sought an alternate DC stage. But a local high school refused her. Pressed again, the D.A.R. dug in. Soon a Marian Anderson Citizens Committee formed, and the NAACP geared up for a fight.

Then on February 27, America heard from Eleanor Roosevelt. The First Lady had championed civil rights since moving into the White House. Only a few months earlier, she had shocked the South, first by simply attending a pro-integration conference in Birmingham, then by sitting in the all-black section. When a cop ordered her to move, Eleanor sat in a folding chair between black and white.

In her weekly newspaper column, “My Day,” the First Lady did not note how badly her husband needed the backing of Southern Democrats. As a member of the D.A.R., she merely raised a question. “The question is, if you belong to an organization and disapprove of an action which is typical of a policy, shall you resign or is it better to work for a changed point of view within the organization?”

In the past, she stayed until she had “at least made a fight and been defeated.” But now, “to remain a member implies approval of that action, and therefore I am resigning.”

On into a chilly spring, the controversy raged. Politicians weighed in. “No hall is too good for Marian Anderson,” New York Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia said. Nearly 70 percent of Americans backed Anderson’s right to sing. The press agreed.

— Philadelphia Tribune: “A group of tottering old ladies, who don't know the difference between patriotism and putridism, have compelled the gracious First Lady to apologize for their national rudeness.”

Some Southern newspapers also supported Anderson.

— Richmond Times-Dispatch: “In these days of racial intolerance so crudely expressed in the Third Reich, an action such as the D.A.R.’s ban. . . seems all the more deplorable.”

By mid-March, it looked as if Anderson, flanked by American flags, might sing outside Constitution Hall. But the NAACP offered a better idea.

Opened just 17 years earlier, the Lincoln Memorial had yet to become America’s public Platform of Justice. No one had performed or even spoken from its steps. But Eleanor Roosevelt pestered her friend, Secretary of the Interior Harold Ickes, and her husband. “Now Franklin,” she often began. “You should. . .” Lobbied by his wife and by Ickes, FDR agreed. “She can sing from the top of the Washington Monument if she wants to,” the president said.

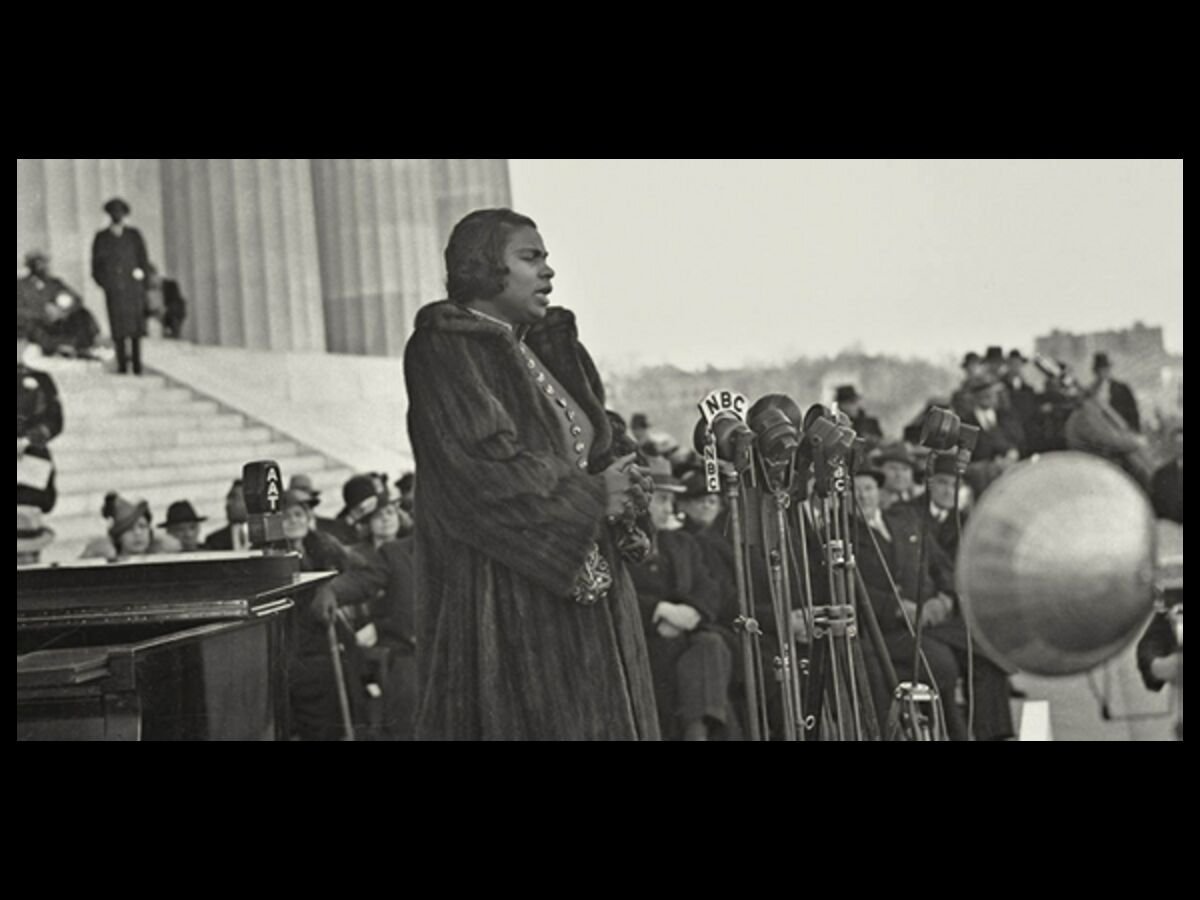

The day before the Easter Sunday concert, it snowed in Washington, dashing hopes for a solid turnout. The next morning was clear and cold. In early afternoon, when Anderson stood on the memorial steps for a sound check, she gazed out on an empty mall. Returning three hours later, she was stunned.

“There seemed to be people as far as the eye could see. I had a feeling that a great wave of good will poured out from those people, almost engulfing me. And when I stood up to sing. . . I felt for a moment as though I were choking. For a desperate second, I thought that the words, well as I know them, would not come.” Then, with 75,000 listening on the mall and millions more on national radio, she began.

Marian Anderson went on to sing around the world, and to represent the U.S. as a cultural liaison at the United Nations. She sang again on the mall during Martin Luther King’s “March on Washington.” And the following year, when she kicked off her farewell tour, her voice once again rang out from the Lincoln Memorial.

“There is hope for America. Our country and people have every reason to be generous and good. . . All the changes may not come in my time; they may even be left for another world. But I have seen enough changes to believe that they will occur in this one.”